|

Russel Wallace : Alfred Russell Wallace (sic) (S453: 1892)

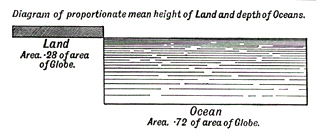

When studying the causes which have brought about the geographical distribution of animals, I was compelled to deal with this question, because I found that it had been the custom of many writers to solve all anomalies of distribution by the creation of hypothetical lands, bridging across the great oceans in various directions [[p. 419]] and at many different epochs; and, having arrived at the conclusion that the distribution of organisms could be more harmoniously and consistently explained without such changes of sea and land, which usually created greater difficulties than those they were intended to explain, I gave, in my "Island Life" a brief statement of the evidence which appeared to me to render such changes exceedingly improbable. This evidence was mainly a summary of the facts and arguments adduced by the eminent men referred to above, and to this I added in my "Darwinism" a difficulty founded on mechanical considerations which seemed to me to furnish a preliminary reason why we should not accept the doctrine of the interchange of continental and oceanic areas without very clear and cogent reasons. Since then some other arguments of this nature have occurred to me, and as the theory of permanence has been recently attacked, by Mr. W. T. Blanford in his presidential address to the Geological Society in 1890, and by Mr. Jukes-Browne in his "Building of the British Isles," it may be as well to consider these difficulties, which furnish, in my opinion, a very powerful argument against the interchange of oceanic and continental areas, and which has the advantage of not requiring any knowledge of the higher mathematics in order to estimate its validity. And, first, it is necessary to clear away some misconceptions as to the proposition I really uphold, since arguments have been adduced which in no way affect that proposition. Thus, Mr. Jukes-Browne quotes Professor Prestwich as saying, "It is only the deeper portions of the great ocean troughs that can claim the high antiquity now advocated for them by many eminent American and English geologists." But this is all that is claimed. For practical purposes I at first took the 1,000-fathom line as, generally and roughly, indicating the separation between the oceanic and the continental areas, because at that time it did accurately divide the continental from the oceanic islands, as defined by a combination of geological and biological characters. It has, however, been since shown that two ancient continental islands--Madagascar and New Zealand--are separated from their respective continents by depths of more than 1,000 fathoms. We must, therefore, go as far as 1,500-, or, perhaps, in a few cases, to the 2,000-fathom line, and this will surely mark out "the deeper portions of the great ocean basins," since only isolated areas exceed 3,000 fathoms. Now, if we look at the deep ocean basins marked out by the 2,000-fathom line, not on Mercator's projection which greatly exaggerates the shallower portion situated in the temperate and polar regions, but on an equal-area projection, such as the map which illustrates Mr. J. Murray's paper,1 we shall see that by far the larger part of all the great oceans are included by this line, and that, for [[p. 420]] the purpose of indicating the isolation of the continents from each other throughout the equatorial and most of the temperate zones, there is very little to choose between the 1,000-fathom or the 2,000-fathom boundary. The latter, however, allows more scope for possible land extensions between the three southern continents and the Antarctic lands, which, during mild epochs, and by means of intervening islands, may, perhaps, have served as a means of communication between these continents. All that is necessary to maintain, therefore, is that existing continents with their included seas, and their surrounding oceanic waters as far as the 1,500-fathom, or in some extreme cases the 2,000-fathom line, mark out the areas within which the continental lands of the globe have been built up; while the oceanic areas beyond the 2,000-fathom line, constituting, according to Mr. Murray's data, 71 per cent. of the whole ocean, have almost certainly been ocean throughout all known geological time.2 It will now be seen that this is a problem which deals with the very broadest contrasts of the earth's surface, and that its fundamental data are on so vast a scale as not to be materially affected by the smaller details of physical geography, or by differences of opinion as to the exact meaning of certain terms. Whether a particular island is more correctly classed as oceanic or continental, whether a certain portion of the ocean should be placed within the oceanic or the continental area, and whether certain rocks were formed in very deep or in comparatively shallow water, are of slight importance, except in so far as they may throw light on the real question, which is, whether the vast expanses of ocean beyond the 1,000-fathom line, forming about 92 per cent. of the whole oceanic area, have ever been occupied, or extensively bridged over, by continental land. It is towards the solution of this great problem that I now propose to submit certain general considerations which appear to me to lie at the root of the whole matter. Comparison of Oceanic and Continental Masses.--In the paper already referred to, Mr. John Murray has carefully estimated both the area of the land and of the water on the earth's surface, and their bulk as deduced from the best available data. Taking the whole area of the globe as 100, he finds the land surface to be 28, the water surface 72. But the mean height of the land above sea-level is 2,250 feet, while the mean depth of all the oceans and seas is 12,456 feet. In this estimate, however, all the inland seas and shallow coast waters are included, and as these, at least as far as the 100-fathom line, are universally admitted to be within the "continental area," we omit them in our estimate of the mean depth of the oceans proper, which are thus brought to something over 15,000 feet, or nearly seven times as much as the mean height of the land. [[p. 421]] The accompanying diagram (taken from my book on "Darwinism") will better enable the reader to appreciate these proportions, which are of vital importance in the problem under discussion. The lengths of the two parts of the diagram are in proportion to the areas of land and ocean respectively, the vertical dimensions showing the comparative mean height and depth. It follows that the areas of the two shaded portions are proportional to the bulk of the continents and oceans respectively. The mean depths of the several oceans and the mean heights of the several continents do not differ enough from each other to render this diagram a very inaccurate representation of the proportion between any of the continents and their adjacent oceans; and it will therefore serve, roughly, to keep before the mind what must have taken place if oceanic and continental areas had ever changed places. It will, I presume, be admitted that, on any large scale, elevation and subsidence must nearly balance each other, and, thus, in order that any area of continental magnitude should rise from the ocean floor till it formed fairly elevated dry land, some corresponding area must sink

to a like extent. But if such subsiding area formed a part or the whole of a continent, the land would entirely disappear beneath the waters of the ocean (except a few mountain peaks) long before the corresponding part of the ocean floor had approached the surface. In order, therefore, to make any such interchange possible, without the total disappearance of the greater portion of the subsiding continent before the new one had appeared to take its place, we must make some arbitrary assumptions. We must suppose either that when one portion of the ocean floor rose, some other part of that floor sank to greater depths till the new continent approached the surface, or, that the sinking of a whole continent was balanced by the rising of a comparatively small area of the ocean floor. Of course, either of these assumed changes are conceivable and, perhaps, possible; but it seems to me that they are exceedingly improbable, and that to assume that they have occurred again and again, as part of the regular course of the earth's history, leads us into enormous difficulties. Consider, for a moment, what would be implied by the building up of a continent the size of Africa from the mean depth of the ocean. By [[p. 422]] comparing the area of Africa with that of the whole of the land, and the depth of the ocean with the mean height of the land, we shall find that if all the land of the globe above sea-level could be transferred to mid-ocean, it would not be sufficient to form the new continent, but would still leave it nearly 2,000 feet beneath the surface. It thus appears that, if the elevation of the ocean floor, and the corresponding sinking of whole continents, constitute a portion of the regular change and development of the earth's surface, there would be not only a chance but a great probability of entire continents disappearing beneath the waters before new continents had risen to take their place. Even the total disappearance of all the large land masses might easily happen; for we see from the diagram that they might one after the other disappear with a corresponding rise of the adjacent portion of the ocean bed and still leave the ocean over the whole earth almost as deep as it is now. But, as will be shown further on, the geological record, imperfect as it is, teaches us that no such submergences have ever taken place. Contour of the Ocean Floor as indicating Permanence.--Before extensive soundings revealed the depth of the ocean and the form of its floor, it was supposed that it would exhibit irregularities corresponding to those of the land, such as mountain-ranges, great valleys, escarpments, ravines, &c. But we now know that the main characteristic of the ocean floor is, that it is a vast undulating plain, the slopes rarely exceeding a hundred feet in a mile except near the margins of the continental areas, while usually the gradients are so slight that they would be hardly perceptible. Contrast this with the forms of all mountain ranges whose general rise for long distances is often five hundred feet in a mile, while slopes at angles of from 20° to 60° are by no means uncommon. Now if we suppose that considerable portions of the ocean depths have been formed by the subsidence of continents, we should certainly expect to find some indication of those surface features which characterise all continents, but which appear to be absent from all deep oceans. In order to account for the actual contours of the ocean on this theory, we must suppose that, during subsidence, all the mountain ranges, peaks, valleys, and precipices were reduced to an almost uniform level surface by marine denudation, which, unless, the process of subsidence were incredibly slow, seems most improbable. Mr. Jukes-Browne, however, does not hold the view that they have been thus denuded, for he approvingly quotes Mr. Crosby as saying that--"the oceanic islands are, of course, merely the tops of submerged mountains, and it is only with the highest points of continents that they can properly be compared." If this is correct, then we ought to find in the vicinity of such islands all the chief features of submerged mountain ranges--precipices, deep valleys and ravines, arranged in diverging groups as they always [[p. 423]] occur in nature. But in no single case, that I am aware of, have any such features been discovered. But a still greater difficulty remains to be considered. If oceanic and continental areas are interchangeable, it can only be because the very same causes (whatever they may be) that produce elevations and subsidences in the one produce them also in the other, and at first sight it appears probable that this would be the case. But if these causes have been at work upon the ocean floor throughout geological epochs, they would have produced irregularities of surface not less but far greater than on subaerial land. This must be so, because subaerial denudation continually neutralises much of the effect of upheaval in the continental areas, while in the ocean depths no such cause or anything analogous to it is in operation. The forces which have been at work in every mountainous region have sometimes tilted up great masses of rock at high angles, upheaved them into huge anticlinal curves, or crushed them by lateral pressure into repeated folds, which in some cases appear to have fallen over so as to reverse the succession of the strata. But, notwithstanding these various forms of upheaval, involving vertical displacements which are sometimes several miles in extent, the surface of the land often shows no corresponding irregularities, owing to the fact that subaerial denudation has either kept pace with upheaval or has even exceeded it, so that the position of an anticlinal ridge may be, and often is, represented by a valley. Now, if we suppose that similar forces have been at work on that portion of the earth's surface forming the bed of the ocean, where there are no such counteracting agencies, we should expect to find irregularities in the ocean floor far greater than those which occur upon the land surface. Still more difficult to explain would be the absence of precipitous escarpments due to faults, which, though frequently showing an upthrow or downthrow of the strata to the amount of many hundreds and sometimes thousands of feet, rarely exhibit any difference of level on the land surface, owing to the fact that subaerial denudation has kept pace with slow and intermittent elevation. But in the ocean depths no such denudation is going on; and we can therefore only account for its very uniform surface on the supposition that it is not subject to the varied and complex subterranean movements which have certainly acted within the continental areas throughout known geological time.3 Equal Range of the Geological Record in all the Continents.--There is one other general consideration which indicates the permanence and continuity of the Continental Areas, and which renders it very [[p. 424]] difficult, if not impossible, to suppose that they have ever changed places with the great oceans. It is, that on all the present continents we find either the same or a closely parallel series of geological formations, from the most ancient to the most recent. Not only do we find Palæozoic, Mesozoic, and Cainozoic rocks everywhere present, but, in proportion as the continents are explored geologically, we find a tolerably complete series of the chief formations. From Laurentian to Carboniferous and Permian, from Trias to Cretaceous, and from Eocene to Quaternary, the geological series appears to be fairly represented not only in continents, but also to a considerable extent in the large continental islands, such as Great Britain and New Zealand. Now this is certainly not what we should expect if the present continental areas had, at different epochs, risen out of the deep oceans. In that case some would have commenced their geological history at a later period than others, having either a late Palæozoic or some Mesozoic formation, or even an early Tertiary for their lowest stratified rock. Others, which had become oceanic for the first time at a later epoch, would exhibit an enormous gap in the series, either several of the Mesozoic formations, for example, being absent, or some considerable portion of both Palæozoic and Mesozoic, or Mesozoic and Tertiary. This would necessarily be the case, because we cannot believe that so vast a change as the subsidence of an entire continent till its site became a deep ocean, and its subsequent elevation till it again became dry land, could possibly be effected in any less extended periods, if at all. Whenever such gaps, or smaller ones, now occur locally, they are generally held to imply the existence of terrestrial conditions, as in the case of China, which, according to Richthoven, has been continental since the Carboniferous epoch. In many cases there is distinct evidence of such conditions in lacustrine or freshwater deposits, dirt-beds, &c. But if a gap of such vast extent both in space and time as that here referred to were caused by the interchange of a continent and a deep ocean, the fact that it was so produced would be clearly evidenced by an almost uniform deposit either of organic or clayey ooze, similar to those now everywhere forming over the oceanic area. Even if we make the fullest allowance for denudation during elevation, sufficient indications of so widespread a formation should be detected. Such a deposit would, in fact, have every chance of being largely preserved, because, long before it rose to the level where it would be subject to denudation by waves or currents, it would, almost everywhere, be overlain by a series of shore deposits, and wherever these latter were preserved on the land surface the oceanic formation would necessarily be found under them. That no such enormous deficiency in the geological series characterises any of the continents, and that no widespread deposit of organic or clayey ooze at some [[p. 425]] definite horizon has been anywhere detected, though such a deposit must have been formed and largely preserved if the whole or any considerable part of a continent had risen from ocean depths at any period of its history, constitutes of itself a very strong argument against any such interchange of oceanic and continental areas having occurred. I have now shown that there are three distinct groups of phenomena which are either altogether inconsistent with any general interchange of oceanic and continental areas, or which render it exceedingly difficult to understand how such interchange could have been brought about. These phenomena are:--(1) The enormous disproportion between the mean height of the land and the mean depth of the ocean, which would render it very difficult for new land to reach the surface till long after the total submergence of the sinking continent. (2) The wonderful uniformity of level over by far the greater part of the ocean floor, which indicates that it is not subject to the same disturbing agencies which throughout all geological time have been creating irregularities in the land-surface, irregularities which would be far greater than they are were they not continually counteracted by the lowering and equalising effects of subaerial denudation. (3) The remarkable parallelism and completeness of the series of geological formations in all the best known continents and larger continental islands, indicating that none of them have risen from the ocean floor during any portion of known geological history, a conclusion enforced by the absence from any of them of that general deposit of oceanic ooze at some definite horizon, which would be at once the result and proof of any such tremendous episode in their past history. I submit that these facts, and the conclusions to be logically deduced from them, form a very powerful à priori argument as against those who maintain the interchange of continents and oceans as a means of explaining certain isolated geological or biological phenomena; such, for instance, as the much-disputed origin of the chalk, or the supposed necessity for land-communication to explain the distribution of certain groups of reptiles or fishes in remote geological times. Before postulating such vast revolutions of the terrestrial surface in order to cut the gordian knot of difficulties which may be mainly due to imperfect knowledge, it will be necessary to show that the considerations here adduced, as well as the great body of facts which have caused many eminent geologists, naturalists, and physicists to hold the doctrine of oceanic permanence, are either illogical or founded on incorrect data. For, surely, no one will suggest that so vast a problem of terrestrial physics can be held to be solved till we have exhausted all the evidence at our command, and have shown that it largely preponderates on one side or the other. The present article is intended to supply a hitherto unnoticed class of arguments for oceanic permanence, and these must of course [[p. 426]] be taken in connection with the other evidence which has been summarised in the 6th chapter of the writer's "Island Life," and also with the admirable "Summary" of the purely physical argument in the 2nd edition of Mr. O. Fisher's "Physics of the Earth's Crust." It is certainly a remarkable fact that writers approaching the subject from so many distinct points of view--as have Professor Dana, Mr. Darwin, Sir Archibald Geikie, Dr. John Murray, Rev. O. Fisher, and myself--should yet arrive at what is substantially an identical conclusion; and this must certainly be held to afford a strong presumption that that conclusion is a correct one.

1"On

the Height of the Land and the Depth of the Ocean," Scottish Geographical

Magazine, 1888. [[on p. 419]]

|