|

Russel Wallace : Alfred Russell Wallace (sic) the Geographical Distribution of Animals (S316: 1879/1880)

These observations are necessary as an introduction to our subject, because there is no branch of Natural History on which [[p. 3]] the theory of evolution has thrown so much light as on the geographical distribution of animals and plants. So long as every species was believed to have been independently created the place where they were found was of little importance. The idea prevailed that each animal had been formed in exact adaptation to its native country, and to that only, and that the chief or perhaps the only reason why the animals of different countries were not the same was that their climates, soils, or other features, were correspondingly different. On this theory it would be said that America had no horses, Australia no rabbits, and New Zealand no pigs, because these animals were not adapted to them. We now know, however, that they are pre-eminently adapted to them; for when introduced they all flourish and increase, often to such an extent as to become a perfect nuisance, and to exterminate or drive away native productions. We therefore now conclude that the reason these animals are not natives of Australia and New Zealand is because they could not reach these countries till man carried them there. This, however, is not a universal explanation, for innumerable fossil horses are found in America (both North and South), and some of these have only recently become extinct. Here, then, we are driven to conclude that some changes took place in America, either in climate or in its animal or vegetable life, which were so inimical to horses as to cause their extinction; that these unfavourable conditions afterwards passed away, but that, the entire race of horses having been extinguished, there was no means of renewing it except by immigration from the Old World. This was prevented by the isolation of America. But when it was effected by man, horses ran wild, and increased both on the prairies of the northern and the pampas of the southern continent. Hence we have to modify our first statement, and to say, that the absence of any particular animal or group of animals from any country depends either on its not having been able to reach the country, or on its having been exterminated, owing to unfavourable conditions, after having reached it or after having developed in it. Thus modified, our statement embodies the fundamental principle of the modern theory of the geographical distribution of animals and plants. To apply this theory in detail to all organisms, and to every country in the world, is, however, at present impracticable, and perhaps always will be so. It requires us to know all the species of living animals and their actual distribution, to have a tolerably complete knowledge of their past history and development, as recorded [[p. 4]] by fossil remains, and to have also a knowledge of the changes that have taken place in the distribution of land and water in past ages, whereby animals have been able to reach countries which are now isolated, or have been formerly cut off from countries to which they now have access. We also require to know the habits and life-history of each animal, so as to know its powers of migration and dispersal, and how far it is possible for it to pass over such barriers as seas and oceans, or lofty mountain ranges. Just in proportion as we are acquainted with all these facts shall we be able to solve the problems presented by the geographical distribution of animals; and we are therefore obliged to confine ourselves to certain groups of the higher animals, more particularly to the land mammals and birds, these being far better known than any other groups; the mammalia being also very rich in fossil remains, whereby we obtain much knowledge of their past history. In order to bring this subject before you in its simplest and most intelligible form, I propose to confine myself in the present lecture, to the phenomena presented by Islands, giving you a somewhat detailed account of the facts in a few typical examples. Islands differ much in their origin, and this difference of origin determines the kinds of animals and plants which inhabit them. They may be divided for our purpose into three classes--1. Recent Continental Islands. 2. Ancient Continental Islands. 3. Oceanic Islands. By Continental Islands we mean those which have been separated from a continent, either recently (in a geological sense) or at some very remote epoch. Oceanic Islands, on the contrary, are such as have never formed part of a continent, but have been produced in mid-ocean. Continental Islands geologically resemble continents, having a variety of formations usually comprising stratified rocks of different ages. Oceanic Islands are always either volcanic or coralline, the only known exceptions being the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean. Recent Continental Islands are always surrounded by a shallow sea (almost always less than 100 fathoms deep), so that they are connected with the continent by a submarine bank, and an elevation of 600 feet would again join them to it. They are generally situated near to continents, but sometimes at a distance of several [[p. 5]] hundred miles, as in the case of Borneo, about 600 miles from Cambodia, the intervening sea being everywhere less than 100 fathoms deep. Ancient Continental Islands are always separated from the adjacent continent by a deep sea, though they are usually no further off than the more recent islands. Thus, Madagascar is separated from Africa by a strait which is about 2,000 fathoms deep, and there is more than 1,000 fathoms between Hayti and the coast of South America. Oceanic Islands are usually situated in mid-ocean and surrounded by very deep seas, examples of which are the Azores, St. Helena, and the Sandwich Islands. But there are some exceptions. Thus, the Cape de Verde Islands, the Canaries, and Madeira, are all within 400 miles of the coast of Africa, while some of the Canary Islands are only 50 miles distant from it; but even these are separated from the mainland by a depth of more than 1,000 fathoms. Such are the physical characteristics of the three classes of islands. Their zoological features are equally well marked. 1. Recent Continental Islands always possess the same kinds of animals as the mainland--mammalia, birds, and reptiles especially--all the more important orders and families being represented, generally by the same, but sometimes by distinct though closely-allied species. Their animal inhabitants correspond, in fact, to what would be found in a fragment now separated from the same continent. 2. Ancient Continental Islands possess animals which are on the whole different from those of the mainland. They always possess mammalia, birds, and reptiles; but many of the families and orders of the continent are wanting, and some which are present in the island are not represented on the continent. 3. Oceanic Islands have no land mammalia, and of reptiles and amphibia either none or very few. Birds are more or less numerous, and more or less the same as those of the continent according as the facilities for their passage are many or few. We will now take in order an example or two of each class of islands, pointing out their peculiarities and the conclusions that may be drawn from them. There is no more perfect and beautiful example on the globe of a recent continental island than that in which we live--Great Britain. This island, as all know who know anything of geology, contains, as it were, a little epitome of Europe. Almost every [[p. 6]] formation, from the oldest to the newest, is found in our country. It is also surrounded by an exceedingly shallow sea, which stretches out so as to include the whole of the islands up to the

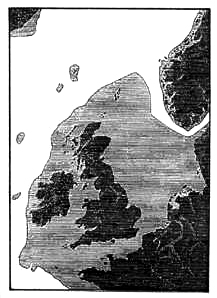

Map showing the effect of an upheaval of the sea bottom around the British Isles, to the extent of 100 fathoms. The half-shade represents the area which would then become dry land; the extent of this area is indicated by the fact that 1,000 square miles on the same scale is represented this square. __ [[i.e., by a square each side of which is about 1/30th of the short (east-west) dimension of the map--Ed.]]. 100-fathom line marked on this map. Outside that line the sea bottom suddenly sinks down, so that a few miles further you get to [[p. 7]] 500 and then 1,000 fathoms, whereas between that and the shores of Europe the whole sea is less than 100 fathoms deep. That is one striking characteristic of recent continental islands. In the case of our own country we know a great deal of its past history. We know that at a comparatively recent geological period this country formed part of the Continent. We have proofs of this, not only in the community of animals which could not have got to us in any other way, but we have some physical proofs of a very interesting kind. For instance, around a great part of the coast of England there are found submarine forests--that is, down at low-water mark, and stretching below, are found the stems of trees growing in the mud, with their roots spreading out just as they originally grew. It is clear that trees could not grow in the sea in the place where they stand, and it is therefore perfectly clear that the land must have been higher or the sea have been lower. These submarine forests are beautifully shown on the coasts of Devonshire and Wales. There are also in Glamorganshire, on the north side of the Bristol Channel, some caves, now opening into perpendicular sea cliffs, which are washed at their base by the sea; yet these caves contain thousands, and sometimes tens of thousands, of the antlers of deer, showing that they must have been surrounded by forest country inhabited by the deer, and that hyenas and bears, whose bones are also found in them, dragged the deer into the caves and devoured them. It is certain, therefore, that a considerable part of the Bristol Channel must once have been dry land covered with forest. But there is a still more striking proof of the former elevation of our island in Scotland, and no doubt there are plenty of other examples in England, namely, old river channels buried hundreds of feet deep in the earth. In boring in the mining district of the lowlands the workmen frequently come across these old river channels, and the borings have shown in some cases their exact course. Some of these old river channels are 260 feet below the present level of the sea. Not only do we know that the land was once higher, but we know that the change took place at a comparatively recent period, because these old river channels are filled up with glacial drift--that is, deposits of the glacial period when man had just come into this country. Well, that height of 260 feet is more than sufficient to join our island to the Continent and make it a part of Europe. Another interesting proof is that dead shells, such as now live in shallow water, have been dredged up off the Shetland Islands [[p. 8]] at a depth of 90 fathoms. These are arctic shells, now inhabiting cold regions, and they always live either between the tide marks or just below the lowest tides, so that these shells found in 90 fathoms of water were once living on the sea-shore. These facts render it perfectly certain--even if we had no land animals to tell us so--that our country was once connected with the Continent. Therefore we are not surprised to find that our animals are practically identical with those of the Continent. We have in Great Britain twenty-eight different kinds of wild mammalia, without counting the bats, which can fly. We must add to these four which we know lived in our country during the historic period, and which have been destroyed by man--the wolf, the bear, the wild ox, and the wild boar. These animals were all hunted in olden time, and have become extinct. That makes 32. When we go further back, into the time when prehistoric men, who made flint weapons, lived in our country, then we have a still larger number of animals, including the mammoth, the rhinoceros, bears, hyenas, lions, horses, bisons, and reindeer, all of which were natives of this country. These and many smaller animals were found at the same time in England and on the Continent, so that when Britain and Ireland formed part of the mainland of Europe they contained at least 50 species of mammalia. The reason we have so few now is, that besides the elevations of land joining England with the Continent there have been subsidences, which reduced our country to an archipelago of very small islands, formed by the mountains of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. The last of these subsidences took place during the glacial epoch, as proved by the occurrence of gravel with marine arctic shells, at an elevation of more than 1,000 feet, in Wales and Scotland. At this period nearly all the mammalia must have perished, and what we now possess must have entered the country during the latest period of elevation, which coincided with the era of the stone palæolithic weapons and the cave men who manufactured and used them. But the emigration of mammalia into a new and barren country recently raised above the sea will be a slow process, and only the larger, more abundant, and hardier species will at first pass over or succeed in establishing themselves. This is shown by the fact that our deficiency is chiefly in the smaller species, for while Germany has 32 rodents (such as squirrels, mice, voles, and rabbits) we have only 13, but we have a total of 32 mammalia against 67 in Germany, which is a considerably larger proportion. Ireland has [[p. 9]] fewer than we have (20 species), because they had a still longer journey to take to reach that country. This is still better seen in the case of the reptiles and amphibia, including our snakes, lizards, frogs, toads, and newts. Of these the small kingdom of Belgium has 22 species, Britain has 13, and Ireland 4--so few that it has led to the common saying that Ireland has no reptiles, which is not quite true. We have thus, I think, sufficiently accounted for what animals our country has, and also for what it has not. There remains, however, to be noticed a small but decided amount of peculiarity in the animals of our country. We possess no peculiar mammal, all being exactly similar to those of the Continent; but we do possess one peculiar bird, the red grouse, which inhabits England, Scotland, and Ireland, but is known in no other country. Its nearest ally is the willow grouse of Norway, which turns white in winter, whereas our bird becomes darker in winter. Besides this, two of our little garden favourites, the coal-tit and the long-tailed-tit, are so differently coloured from their Continental allies that some naturalists class them as distinct and peculiar species. Among our fresh-water fishes we have some very remarkable cases of peculiarity. It has been long known to fishermen that many of the mountain lakes of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland produced peculiar kinds of trout, but few of these had been carefully examined till Dr. Günther, of the British Museum, obtained specimens from all our chief lakes, and compared them with those of the Continent, and he has come to the conclusion that we possess no less than eleven different kinds of trout which are altogether peculiar to our islands. One is peculiar to the lakes of the Orkney Islands, one to Loch Leven, and another to Loch Killin, in Scotland; one to the Llanberris lakes in Wales, three to the lakes of Ireland, while some are found both in Wales and Scotland. Let us see how these curious facts can be explained. Our red grouse is probably a descendant of the willow grouse of Norway, which entered our country when it was united to the Continent during the latter part of the glacial period. After the separation it remained and spread over all the heathy parts of the country, and as the climate became milder, and there was less snow in winter, it gradually lost the property of changing white at that season, because it was better protected and concealed by remaining the colour of the heather among which it lives. To understand the exact mode in which such changes occur Mr. Darwin's "Origin of Species" must be referred to. [[p. 10]] The slight changes in the tits would be brought about in a similar way, owing to some slight peculiarity of tint in our woods rendering it advantageous for the colour of the birds to be changed accordingly; and it is to be remarked that the change has occurred in birds which do not migrate to the Continent, and which therefore must become adapted to the conditions of the country they inhabit, or cease to exist. The case of the peculiar lake fishes is more difficult, because we know less of their mode of life, and especially of how they pass from one part of the country to another. Yet that their eggs are somehow conveyed for long distances is certain, because we have the very same species inhabiting remote mountain lakes in both Wales and Scotland. Mr. Darwin remarks that small living fish have been carried through the air and dropped by whirlwinds, while the ova may be carried in the same manner, or by becoming attached to the feet of aquatic birds. It is also possible that some of the fishes may have survived the glacial period, and during the time that the whole country was buried in ice some of them may have been carried in the pools which often exist on the surface of glaciers to great distances. It may be said that these causes are very improbable, and could only have acted very rarely. But this is just what we want; for if the eggs of fishes were carried frequently from one lake to another then species peculiar to a lake could never have arisen. It is because a fish, once brought to a lake by a rare accident, has remained undisturbed there for perhaps thousands of years that it has become modified. All that time it has been subjected to peculiar conditions. The temperature, the colour, and the composition of the water are peculiar, as are the food it can obtain and the dangers it has to avoid. In time it becomes adapted to all these special conditions, and in doing so becomes slightly modified in colour, form, and habits, so as to form a new species. We see then that the animals which inhabit our country are, both in their peculiarities and deficiencies, sufficiently accounted for by what we know of the country's past history. We will now take one more example of a Recent Continental Island, but one which is considerably less recent than Britain, namely, the island of Formosa, which, instead of being in the temperate zone, is situated close upon the tropics, about a hundred miles from the coast of China. The island was absolutely unknown to naturalists a very few years ago. But one of our consuls in [[p. 11]] China, a gentleman named Swinhoe, who was excessively fond of natural history, was made consul in Formosa, and he devoted himself most energetically to the study of the natural history of the island, and we now know a great deal that is very interesting about it. The island, which was named Formosa by the Portuguese, from its extreme beauty (formosa meaning beautiful in the Portuguese language), is about half the size of Ireland. In the centre it has a magnificent chain of mountains, rising to a height of 12,000 feet, so that, although near the tropics, their summits are covered with snow during a great part of the year. The lower parts of these mountains and valleys are covered with magnificent forests, so that in every respect this island is well adapted to support a great number and variety of animals. That this is a continental island is proved by the characteristic feature that the sea around it is less than 100 fathoms deep; and though the island is comparatively small it contains the large number of 30 species of true land mammals, not counting bats. This is a very large number, for in the adjacent coast districts of all tropical China there are only 34 or 35. This is very different from what is found in our country, where we have a much smaller number than the Continent. But the richness of Formosa in animal life is no doubt due to the variety of its beautiful mountains and forests, and to the probable fact that it has not been depopulated, as our country has, by sinking beneath the sea and rising up again. Among these 30 species of mammals, 13 are peculiar, namely, a monkey, a mole, a civet, a pig, two kinds of deer, a goat-antelope, several mice, and three flying squirrels. Birds are also very numerous, 128 species of land birds being known, of which 42 are peculiar to the island. This great amount of peculiarity indicates a long period of isolation, although the island, like our own, stands on a submarine bank less than 100 fathoms below the surface. But the comparative antiquity of the island is still more clearly shown by the peculiar affinities of several of its mammalia and birds, which in several cases are either identical with or allied to species not found in China, but inhabiting distant countries. Thus the clouded tiger and Asiatic wild cat inhabit Formosa and the Malay Archipelago, but are unknown in China. One of the deer and the goat-antelope are also allied to Malay species, as are two of the flying squirrels; while the spotted deer, the wild pig, and the fruit-bat of Formosa are allied to peculiar Japanese species. This all proves that there must have been a great change in the distribution of animals since the time when Formosa was separated [[p. 12]] from the mainland, and as such changes are slow it proves a great lapse of time. Birds exhibit the same phenomenon even more strikingly; for more than half the peculiar birds of Formosa have their allies, not in China, but in such remote regions as the Himalayas, the Nilgherries in Southern India, the Malay Islands, or Japan; and many of them are totally unlike anything found in China. The lapse of time which has allowed such changes of distribution to take place has also been sufficient for so many of the species to become changed by long isolation under peculiar conditions. But there are some few species which have resisted this process of change, although their distribution has been greatly altered. Four birds--a red-breasted fly-catcher, a handsome wood-pigeon, a spotted hawk-eagle, and a brown wood-owl, are found only in Formosa and the Himalaya Mountains, while four other Formosan birds inhabit different parts of India and the Malay Islands, but not China. Here then we have an island which in every respect answers to our definition of a recent continental island, but has yet been separated from the continent sufficiently long to allow of considerable change in the species of animals, and also of considerable change in their distribution. Now as our own island dates back to the close of the glacial period, and exhibits hardly any such changes, we may be sure that Formosa dates very much further back, and must have been an island during some considerable portion of the Pliocene period. We will now go on to examine an Ancient Continental Island, and there is no better example than Madagascar. This great island is separated from the African continent by a channel about 250 miles wide, and more than 10,000 feet deep. It is larger than the whole of the British Isles. It has a great central plateau and lofty mountains, a varied geological structure, a luxuriant vegetation, and a tropical climate. It possesses about 60 different kinds of land mammalia, besides bats, and has therefore certainly been connected with some continent. But these mammalia are very peculiar, and do not at all resemble those which now chiefly inhabit Africa, which, as you know, is remarkable for its numerous monkeys and baboons, its lions, leopards, and hyenas, its zebras, rhinoceroses, elephants, giraffes, buffaloes, and antelopes. Not one of these animals, and nothing like them, is found in Madagascar, and thus the first impression [[p. 13]] would be that it cannot possibly have derived its animals from Africa; but a closer examination may lead us to alter our opinion. Considerably more than half the 35 mammals of Madagascar are lemurs. These are singular animals, of low organisation, usually considered to be the lowest of the Quadrumana, or monkey tribe, but by some naturalists classed as a distinct order. Lemurs are found in Africa, and also in tropical Asia and the Malay Islands, but those of Madagascar are very peculiar, all forming distinct genera, and one a distinct family. Here then we have no indications of a specially African origin. The next important group are the Insectivora, to which our mole and hedgehog belong. In Madagascar there are about a dozen species, but strange to say all but one belong to a family only found elsewhere in the West India Islands! and that one is a shrew mouse, such as are found all over the world. We then come to the Carnivora, which consist chiefly of eight species of civets, all of peculiar genera, but many of them most nearly allied to African genera. The only other animal of importance is a river hog belonging to an African genus; but as these animals are good swimmers it may have reached the island without any actual land union; and the same may be said of the hippopotamus, whose remains have been found in a semi-fossil condition. The birds are equally remarkable. There are more than a hundred peculiar species of land birds, and only twelve found elsewhere--some in Africa and some in Asia. The plantain-eaters, the barbets, the honey-guides, the glossy-starlings, the ground-hornbills, and other peculiarly African families, are quite unknown; and there are instead of these thirty-five peculiar genera, most of which have no near allies in any part of the world. Of the peculiar species, however, sixteen belong to African genera, while only about five belong to Asiatic genera. Among the African allies are a guinea-fowl, a parrot, and a cuckoo, all birds which cannot cross over wide arms of the sea. Turning for some further light to the reptiles, we find that many of the African groups of snakes are absent, and that there are instead three peculiarly American genera. The lizards are more African, but there is one group which is only found elsewhere in America and Australia. We find in these curious facts indications of an enormous lapse of time, which has allowed for great specific changes, as well as great changes in the general distribution of animals. It is in fact the case of Formosa very much exaggerated. [[p. 14]] The extraordinary affinity of some of the Madagascar Insectivora and snakes for those of the West Indies and South America has greatly puzzled naturalists, and it has even been suggested that there was once a continent running quite across from Madagascar to the West Indies; that this continent completely disappeared, leaving a fragment only in Madagascar; and that subsequently Africa was formed. But when we consider the depths of the intervening oceans, and especially that, after all, these affinities are exceptional, we shall find that no such enormous changes are necessary, especially as we have many facts which point the way to the true solution of the problem. All the large and characteristic African animals, whose absence from Madagascar is the first great fact in its natural history, inhabited Europe and Western Asia as far as Northern India during the Miocene period. About the same time we know that a sea cut off tropical Africa from the northern continent, and the natural inference is that it was only when that sea-bed was raised and Africa joined to Europe and Asia, that all these animal forms entered Africa, and subsequently, as the climate became unsuitable, became extinct in Europe. But in the Eocene and Early Miocene periods we know that the distribution of animals was very different from what it is now. Lemurs were then found in Europe and America, and opossums, now confined to America, also inhabited Europe. We believe then that the types now common to Madagascar and remote parts of the world were then widespread over Europe and Asia, and reached Madagascar during its early connection with the continent. The birds which are of Eastern affinities probably reached it by means of islands in the Indian Ocean, of which the Laccadive and Maldive coral reefs, the Chagos Islands, and the extensive submarine bank of the Seychelles, are the relics. Madagascar therefore is an island which dates back certainly to the Miocene, probably to the Eocene, period, and has preserved to us in greater abundance than elsewhere some of the animal forms of that ancient world. We will now pass to the third class of islands of which I spoke--the Oceanic Islands; and to illustrate these I will take two examples, the Galapagos Islands, which are 600 miles from the west coast of South America, and the Azores, in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean. The Galapagos are a group of considerable extent, separated from South America by a sea 10,000 feet deep. Like almost all oceanic islands they are entirely volcanic, and [[p. 15]] possess no indigenous mammalia. There are rats and mice, but these were conveyed thither by ships. They possess reptiles--and it is a curious question how they got there--living tortoises of two different kinds, and one species extinct. The living tortoises are of enormous size, equal to that in the Zoological Gardens, London, which is six feet long, and able to carry two men standing on its back. These tortoises live to a great age, probably several hundred years. They have been kept for a hundred years without increasing much in size. The buccaneers and traders of old who visited the islands used to capture quantities of these tortoises, keep them alive, and kill them when wanted, and thus all the largest have been destroyed, and those now living are the younger and smaller ones. There are also in these islands five species of lizards, all of American families or genera. One of them is a marine lizard, which is found nowhere else, and lives in the sea like the old lizards of the Lias period. Though it is marine it belongs to a family abundant in America, and which inhabits trees. These lizards undoubtedly originally came from America, and have become modified by living in this volcanic island with little vegetation. How their ancestors got to the islands is a problem not yet solved. Perhaps their eggs were floated there by the sea. There is no island in the Pacific where you do not find lizards, though there may be no mammalia, frogs, toads, or snakes. In the Galapagos there are two species of snakes, almost identical with those found on the mainland, and these may have been conveyed in ships, because snakes often conceal themselves amongst the cargo. The birds are exceedingly interesting, there being 57 species, and more than half of them belong to peculiar genera; but they are all allied to American birds, so that it is certain their ancestors came from America. There are 31 species of land birds, and of these 30 are peculiar to the Galapagos. It is found that those that have changed most are forest birds that do not migrate, and those that have changed least are birds that wander about more and do migrate. The one bird that has not changed at all is perhaps the most interesting bird on the continent of America. It is known as the rice-bird, or "bob-o-link," its scientific name being Dolichonyx oryzivorus. It breeds in Canada, and migrates to the Bermudas, and is found all over the United States, and right away to Paraguay in South America, so that it is the greatest wanderer of any land bird in America and therefore it is not so remarkable that it should have found its way to these islands. [[p. 16]] The chief reason why the birds of the Galapagos have become so much altered is their being isolated. If fresh emigrants keep coming to an island there is little chance of the race becoming modified, because the breed is kept pure. The migrating rice-bird keeps the race pure; but the other birds, which come more rarely, have been subjected to, and modified by, the altered conditions of the islands. We shall see the reason why very few birds migrate to these islands when we have examined the next group--the Azores. The Azores or Western Islands form the best contrast to the Galapagos, for though equally oceanic they are temperate instead of tropical, and are situated in the stormy North Atlantic instead of in the calm equatorial Pacific Ocean; and this difference of position has resulted in a great difference in their animal inhabitants. The Azores have no mammalia and no reptiles. There are 22 different kinds of land birds; but instead of being all but one peculiar, as in the Galapagos, there is only one peculiar, all the rest being identical with European birds. This is a most remarkable fact, and is at first very puzzling. It has, however, been clearly ascertained by residents on the islands that the reason of this identity of the species with those of Europe is simply this--the migration of these birds is still going on. The Azores are situated in a very stormy sea, and are subject to violent storms, which blow from all points of the compass, especially in spring and autumn. The regular winds are westerly, and if these winds brought the birds, then they ought to be American, but there is not a single American bird. The interesting fact is this, that after every great storm in spring and autumn the people invariably find some new birds in the islands which they never saw before. These birds are generally watched for and shot. Sometimes there are only one or two fresh birds, and they very rarely maintain themselves, not being in sufficient numbers or the islands are not adapted to them. But some of the 18 permanently resident kinds also came in these storms, and the original migration which took place thousands of years ago is still kept up by birds coming every few years from the same country, and thus the breed is kept pure. The result is that the birds of the Azores may be said to be every one identical with those of Europe, except the bullfinch, which is a bird that does not take long flights, and it is presumed got blown there once a long time ago and has seldom come since. The result is that the peculiar conditions of the climate, food, &c., have acted upon it [[p. 17]] so as to modify it into a distinct species. An interesting proof that this is the mode in which these islands have been peopled is shown by the number of species in the different sub-groups. The Azores consist of about 20 islands, and they are separated into three groups--Eastern, Central, and Western. The central group is the largest. If, as some people maintain, these islands once formed part of the European continent, we should expect to find the largest number of animals and birds in the central group. On the contrary, the eastern group, which is the smallest, has the most birds, showing that the eastern group, which is nearest to the Continent, first receives the majority of the emigrants, and that many go no farther; for the central group has less, while the western group has the fewest. This fact agrees with the theory that these birds are simply stragglers from Europe. The insects show the same phenomena, being mainly identical with those in Europe. The plants, too, are decidedly European, with about ten per cent of peculiar species. Thus we see that the same cause has operated in every case. We learn this important fact, too, that it is not the currents of the ocean that help chiefly to stock islands with plants, insects, and birds, and it is not the ordinary winds that help them there; but it is the violent and occasional storms. By these storms birds get caught up against their will, and are carried out to sea, and then are obliged to fly with the storm. No doubt for every one that alights on these islands hundreds perish; but the few that arrive serve as the parents of a fresh stock. Now we see the reason why the Galapagos have such an immense number of peculiar species. The reason is that the sea around is remarkably calm, as almost all seas are on the equator. There is hardly such a thing as a storm known there, and comparatively light winds. The consequence is, that there is no regular migration of birds to these islands, and the few that do reach them come at such remote intervals that they do little towards keeping up the purity of the original stock. I will, in conclusion, recall to your memory the three classes of islands we have been studying-- 1. We have Recent Continental Islands, always connected with a continent by submarine banks of little depth below the surface; of varied geological formation, like that of the continent; and possessing all the chief types of mammalia and birds, either identical with continental species or, if different, closely allied to them. These have all been separated from their continents during the later portion of the Tertiary period. [[p. 18]] 2. We have Ancient Continental Islands, always divided from the continent by much deeper sea; of varied geological structure; possessing mammalia of a few types only, and those mainly of low organisation; and many of their productions showing affinities for very remote portions of the globe. These have been separated from their continents during the early Tertiary, or perhaps even during the Secondary period, when both the forms of life and their distribution were very different from what they are now. 3. We have the Oceanic Islands, always surrounded by very deep sea; either entirely volcanic or of coralline formation; always without any indigenous mammalia or amphibia; with a few reptiles; and with birds, either very peculiar or identical with those of the nearest continent, according as the physical conditions are favourable to their transmission or otherwise. I have now been able to give you an outline of only a small portion of a very large subject; for every island is a special study of itself, no two being alike in their past history or present relations. Of Continental Islands the Malay Archipelago contains some most interesting examples; Borneo and Sumatra being almost as recent as Britain, while Java is nearly as old as Formosa. Japan, too, is another group of Recent Continental Islands, perhaps of about the same age as Java. Celebes is an Ancient Continental Island of especial interest, though not so old as Madagascar. The West Indies (the larger islands) are perhaps nearly as old, though with a less varied fauna. New Zealand may be called a Continental Oceanic Island--continental in geological structure and in former extent--oceanic in having probably been never united to a continent since mammalia were abundant, or if once united then afterwards submerged. Of true Oceanic Islands the Sandwich Islands, St. Helena, the Canaries, and the Bermudas, all offer points of special interest; but in the case of most of these islands our knowledge is unfortunately imperfect. You will see therefore that, without touching upon the great continental masses of land, the islands of the globe offer materials of intense interest to the naturalist who studies not only the present but the past history of the animal world; and I trust that I have succeeded in making clear to you the nature of the zoological problems they present, and have also enabled you to understand the principles by which the solution of such problems may be successfully attempted.

|