|

Russel Wallace : Alfred Russell Wallace (sic)

"Our first example of the Staphylinidæ is one of the finest, in my opinion the very finest, of that family. It is called scientifically Creophilus maxillosus, but has, unfortunately, no popular name, probably because it is confounded in the popular mind with the common black species, which will be presently described. Its name is more appropriate and expressive than is generally the case with insect names. The word Creophilus is of Greek origin, and signifies 'flesh-lover,' while the specific title, maxillosus, signifies 'large-jawed.' Both names show that those who affixed them to the insect were thoroughly acquainted with its character and form, for the Beetle is a most voracious carrion eater, and has jaws of enormous size in proportion to its body. The colour of this beetle is shining black, but it is mottled with short grey down. "In some places this Beetle is tolerably plentiful, but in others it is seldom if ever seen. It can generally be captured in the bodies of moles that have been suspended by the professional mole-catchers, and, indeed, these unfortunate moles are absolute treasure-houses for the coleopterist, as we shall see when we come to the next group of Beetles. A figure of this insect is given on woodcut No. vii. Fig 3. It is the only British insect of its genus which is distinguished by having short and thickened antennæ, smooth head and thorax, and the latter rounded." The descriptive portion of this characteristic passage could be easily compressed into two or three lines. In the other twenty we are told that the original describers of the insect were well acquainted with it, that the public are not, and that moles caught by professional mole-catchers are unfortunate! Turning to page 447, we have a moth described as follows:-- "The first family of the Geometræ is called Urapterydæ, or Wing-tailed Moths, because in them the hinder wings are drawn out into long projections, popularly called 'tails.' In England we have but one insect belonging to this family, the beautiful, though pale-coloured, swallow-tailed moth (Urapteryx sambucata). The generic name is spelt in various ways, some writers wishing exactly to represent the Greek letters of which it is composed, and others following the conventional form which is generally in use. If the precisians are to be followed, the word ought to be spelt Ourapteryx. "There is no difficulty in recognising the moth, the colour and shape being so decided. Both pairs of wings are delicate yellow, and the upper pair are crossed by two narrow brown stripes, which run from the upper to the lower margin. These stripes are very clear and well defined, but besides these are a vast number of very tiny [[p. 66]]

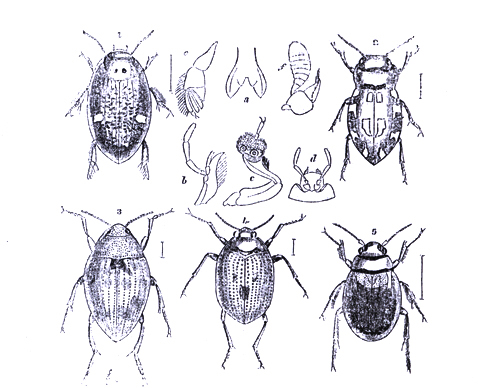

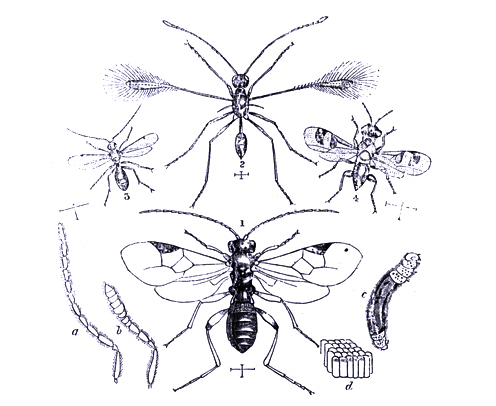

streaks of a similar colour, which look as if they had been drawn in water-colours with the very finest of brushes, and then damped so as to blur their edges. The hind wings have only one streak, which runs obliquely towards the anal angles, and, when the wings are spread, looks as if it were a continuation of the first stripe on the upper wings. The shape of the moth almost exactly resembles that of the Brimstone Butterfly, described on page 393. "The larva affords an admirable example of the twig-resembling caterpillars. It is exceedingly variable in colour, but is always some shade of brown. It has seven bud-like humps, and a few pale stripes along the sides. It [[p. 68]] is a very general feeder, and may be found on a considerable number of trees and plants. It is quite common, and but for its curious form, would certainly be found much more frequently than is the case. The perfect insect appears about July, and can be beaten out of bushes and hedges. Though the wings are large, they are thin and not very powerful, so that there is no difficulty in capturing the insect." Of course much of the book consists of more interesting matter than this, but hundreds of pages are filled with such verbose and meagre passages as those quoted, which are far more repulsive to the learner than the most condensed and technical description. Those given in Stainton's Manual, for instance, contain more than double the actual information in about one fourth of the space. The book is illustrated by copious woodcuts in the letterpress and by several whole-page pictures. The former are most admirable, and do great credit to the artist, Mr. E. A. Smith. We select a group of Water Beetles (Cut vi.), and one of the minute and curious parasitic Hymenoptera (Cut xxxii.) as examples of these excellent figures, which would do credit to a far more scientific work. The whole-page illustrations are by another hand, and are in every respect inferior. Some of them contain fair presentations of insects in their haunts, but the vegetation is generally badly drawn, and the plants said to be figured are often quite unrecognisable. The best and most artistic picture is Plate VIII., representing a group of Neuroptera with aquatic vegetation. The worst is Plate XIX., representing aquatic Heteroptera. The insects are pretty well drawn, but the plants are dreadful. One of them is said to be the Starwort (Aster tripolium). What is meant for this stands prominently out in the view; but the artist has evidently never seen the plant, and, trusting to his imagination to invent something suited to the name, has perched three thick six-rayed star-fish on bending stalks. We venture to assert that no plant having the faintest resemblance to this monstrosity forms part of the British flora, and its introduction into a modern work on natural history is most discreditable. It is painful to have to speak in these terms of the work of an author who has done so much to popularise natural history as Mr. Wood, but we must protest against mere book-making; and in this case there could be no pretence of a want to be supplied, since the excellent series of "Introductions" published by Messrs. Reeve and the more general works of Prof. Duncan, Dr. Packard, and others, are far better guides to the student or to the general reader than such a hasty and imperfect compilation as the present volume. A. R. W.

1. "Insects at Home: Being a Popular Account of British Insects, their Structures, Habits, and Transformations." By the Rev. J. G. Wood, M.A., F.L.S., &c. With upwards of 700 Figures by E. A. Smith and J. B. Zwecker. Engraved by G. Pearson. (Longmans, Green, and Co. 1872.) [[on p. 65]]

|