|

Russel Wallace : Alfred Russell Wallace (sic) (S102: 1864) The Psittaci or Parrots are an extensive and very isolated group of birds ranging over the tropics of the whole world, but, with the exception of those lands of anomalies, Australia and New Zealand, rarely found in the temperate and cooler regions. As nearly as I can estimate, the number of species of these birds known at present amounts to 365, grouped in about thirty-six genera and five families. The manner, however, in which these species and group are distributed over the globe is very remarkable. Taking the zoological regions established by Dr. Sclater, we find the following approximate numbers--

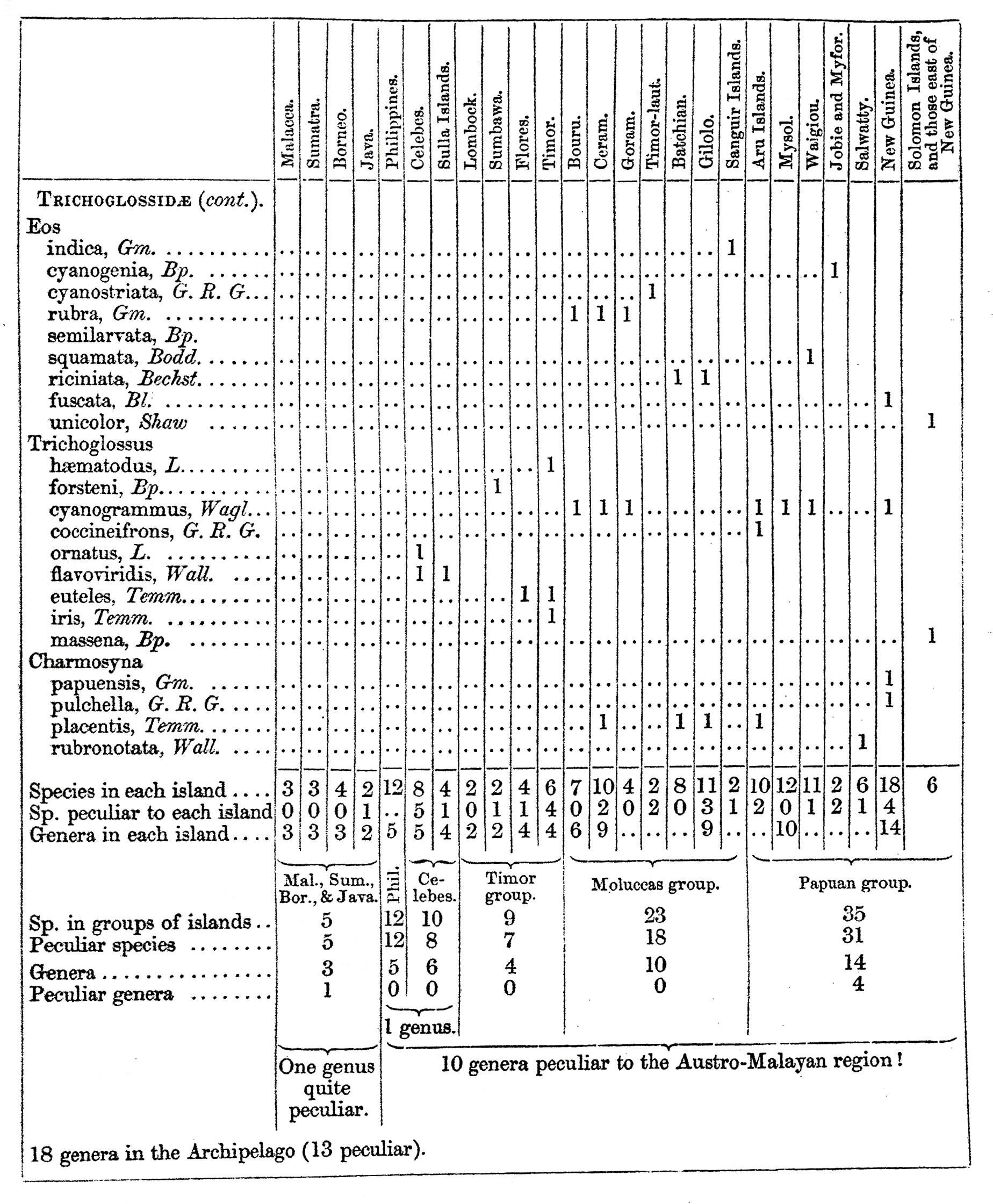

showing a remarkable poverty in the Indian and Ethiopian regions, both in species and groups; abundance of species in the Neotropical (S. American) region, with comparatively few genera; while the Australian region not only contains more species than the American, [[p. 273]] but possesses nearly three times as many genera, and nearly twice as many as all the other regions combined. More remarkable still, the whole of the Indian, Ethiopian, and American Parrots belong to one great family group, the Psittacidæ, indicating a general uniformity of organization; while those of the Australian region mostly belong to three other distinct families--the Brushtongues or Lories (Trichoglossidæ), the Cockatoos (Plyctolophidæ), and the Broadtails or Ground-Parrots (Platycercidæ)--together with a few of the Psittacidæ, which last, however, are confined to the Malayan portion of the region. These facts are of the highest interest in their bearing on the probable origin of the whole Psittacine group; for it is natural to suppose that in that portion of the earth's surface where the species are now most numerous, the forms most varied, where the most singular modifications of structure occur, and where both the highest and the lowest developments of the group are to be found, would be its true metropolis and original birthplace. I believe, therefore, that the Parrot type originated in the Australian region--a region now consisting almost entirely of broken land and scattered islands, but which, there is every reason to think, was once a continental area. Confining our attention now to the Australian region only, we may divide it into three subregions--Australia, the Pacific Islands, and the Austro-Malayan group--each of which has a distinctive character. The Platycerci and the Cockatoos are more particularly the features of Australia and Tasmania, which have also a few Trichoglossi, but no Psittacidæ. The Coriphili, Nestors, and Strigopidæ are confined to the Pacific Islands, which have also Platycerci, but no Cockatoos. The crimson Lories are entirely restricted to the Malayan district, which has also abundance of Cockatoos, but few Platycerci, and several peculiar genera of Psittacidæ. Thus four out of the five families into which the order is divided are found in the Austro-Malayan district; they all extend into every part of it, and they are all represented by abundance of species, and three of them by numerous peculiar genera and even subfamilies. The Australian subregion possesses three of the families only, and has a smaller number both of genera and species; but it has a large proportion of peculiar genera, and is preeminent in its numerous forms of Platycercidæ and Plyctolophidæ. Only three families and four genera extend to the Pacific Islands, but three of the genera are quite peculiar to them. The following table shows these proportionate numbers at one view:--

We thus see that the preeminence both in species, genera, and families is with the Austro-Malayan region, and we have therefore an à priori reason for considering it to be the most ancient, and to

Undoubtedly the most highly organized form of Parrot is the Trichoglossine or Brushtongue family, in which the whole structure is modified to enable these birds to derive a considerable portion of their subsistence from the nectar of flowers. The bill is unusually small, elongated, and compressed, so that it may readily enter the corolla; the tongue is large, long, and very extensible, and can be thrust down to the very bottom of the nectary; and the papillæ of the terminal portion of the upper surface are developed into erectile fibres, forming a double brush, which rapidly gathers up all the honeyed secretions of the blossom. In correlation with this structure the species are mostly of small size, of graceful forms, and have powerfully grasping feet--qualities that enable them to climb actively among the twigs and branches, and to cling in any position to the waving sprays of blossom. They have also elongated wings and a powerful flight, which give them the means to traverse the whole area of their range, and discover at the right moment the flowering trees which are so attractive to them, the period of blossoming in tropical regions being very limited for each species. These extremely interesting birds are spread over the whole Australian region, while not one of them has been found beyond its limits; but it is in the Austro-Malayan district only that they are very abundant and of the most varied forms; for it is here that four out of the six genera are exclusively found. Three of these genera form a natural subdivision of the family, which may be called the Loriinæ, and comprise all those beautiful birds the ground-colour of whose plumage is vivid crimson, and which are commonly known as Lories. Of these the genus Eos may be considered the most typical, since the species have completely lost the green colouring which is so characteristic of Parrots generally, and by their activity, elegance, and more powerful flight show that they are the most highly developed in the Trichoglossine series. The vivid red colour which is so characteristic of the Lories here reaches its maximum in such species as E. rubra and E. cardinalis. This fine group, consisting of three genera and at least eighteen distinct species, has a singularly restricted range, being confined to an elongated tract comprising New Guinea and the islands east and west of it, from the Moluccas to the Solomon Islands. If we look at this area marked out upon a map1, we must be at once impressed with the idea that we have here roughly indicated the much greater extent at a recent period of the large island of New Guinea, the north-western portion of which seems even now to be undergoing a still further segmentation. This idea receives confirmation from the fact that almost every bird found in this area has its closest allies in New Guinea; and as we approach the central mass, the variety of forms becomes greater. The genera Monarcha and Mimeta here have their maximum development; and [[p. 275]] Tanysiptera, as abnormal among Kingfishers as Lories are among Parrots, has almost exactly the same limits of distribution as they have. Within these limits are found some of the most curious forms of Parrots, the giant black Cockatoo (Microglossus) and the dwarf of the whole order (Nasiterna), the bare-headed Dasyptilus and the elegant little Charmosyna. Tanygnathus has the range of Eos, but extends north-westwards to Celebes and the Philippines; Geoffroyus south-westwards to Timor and Flores; while the remarkable genus Eclectus has exactly the same range as the Lories, whose attire it seems to mimic, for in it alone are found Parrots whose only colours are red with a portion of blue and black. This coincidence of the range of the red Psittacidæ with that of the red Trichoglossidæ is a very curious fact, and clearly intimates that these gay tints are not mere sports of nature, or designed for the delectation of man, but have a close connexion with the life-history of the creatures which they adorn, and probably subserve an important though hidden object in the economy of these groups. The whole number of Parrots known to inhabit this Loriine region is fifty-four, belonging to no less than fifteen genera, of which eight genera are altogether peculiar to it. This is very remarkable when we compare it with Australia, which, though many times more extensive and also exceptionally rich in this family, possesses, with a rather larger number of species, about ten genera, of which six or seven only are peculiar to it. But Australia has been comparatively well explored in every part of its great extent, and, though a few more species may be discovered, we cannot expect it to produce any new forms of Parrots. New Guinea, on the other hand, the centre and primary mass to which the surrounding islands are but satellites, is a terra incognita. Few persons are aware that every New Guinea bird, beast, or insect we are acquainted with, has been obtained in the northern peninsulas of that country, which, as I before remarked, seem just about to be converted into islands; while the true island itself, a vast tract of forest and mountain, 800 miles long and 500 wide, is absolutely and entirely unknown. The whole of the other islands in this region which have been visited by any naturalist will not make up a tenth of this vast area; and as the mere outskirts of this unexplored land have yielded a number of remarkable genera and hosts of species which do not extend to the surrounding islands, we may be sure that the remarkable concentration of peculiar forms of Parrots which the Loriine region exhibits, even with our present imperfect knowledge of it, is very far below the reality. I believe, therefore, that we have every reason to consider New Guinea as being that still existing portion of what was once the great tropical Pacific continent to which I have alluded; and in the crimson Lories, the black Microglossum, the Birds of Paradise, and the great Crowned Pigeons, we have but a remnant and a sample of the strange and beautiful forms of life that once inhabited it, and many of which may still remain to be discovered in the untrodden Papuan forests. The genus Trichoglossus ranges over the whole of Australia and nearly the whole of the Austro-Malayan Islands, the most [[p. 276]] remarkable exception being the northern Moluccas (Gilolo, Batchian, and Morty), which do not seem to possess it. The small species in which the sexes differ, and which are best placed with Charmosyna, are, however, found in these islands. Celebes, Sumatra, Timor, and Aru have each species of Trichoglossus peculiar to them. The Platycerci are but poorly represented in the Austro-Malayan Islands, and seem to be hardly at home in the damp tropical forests. They have the same range as the Lories, but extend also to the Sulla Islands; and a species of an Australian form inhabits Timor. We now come to the Cockatoos, another most characteristic Australian form which ranges over the whole Australian region, except the Pacific Islands, marking out the limits of that region in the Malay archipelago by reaching Celebes and Lombock, and sending one species into the Philippine Islands, which are considered to belong to the Indian region. We must first remark that the genus Cacatua has a wider range in the Australian region than any other, occupying every island in the Australian and Austro-Malayan subregions, and always existing in considerable abundance. This indicates a dominant group, which has great capacities for increase and self-preservation and great powers of diffusion. It is therefore not wonderful that one species should be found to have penetrated beyond its true home. That this was due to greater facilities for emigration at a comparatively recent epoch in the existence of the genus, is indicated by the fact that, whereas throughout the rest of the archipelago the species of Cacatua are much restricted, each island or small group of islands possessing its peculiar form, in the Philippines one species ranges over the whole of that extensive region. One of the most interesting genera of Parrots in the archipelago and in the world is undoubtedly Prioniturus, which exhibits the only instance in the whole order of a spatulate or racket-shaped tail like that of the Motmot; but in this case the perfectly bare and smooth shaft is produced by a natural process of growth, as in the King Bird of Paradise. The four species of this remarkable genus are equally divided between Celebes and the Philippines, and present a most curious case of the restricted range of a well-marked group. An exactly analogous case among Mammalia is the genus Cynopithecus, a form of baboon completely unlike anything else in the East, and confined to the Philippines, Celebes, and the small adjacent island of Batchian, into which it was probably introduced. While these two groups of islands have thus evidently had once a closer connexion than at present, they both possess a striking individuality which separates them from the primary regions to which they respectively belong. The Philippines stand alone in the Indian region by the absence of all large carnivora and pachyderms, as well as of Apes and Monkeys, (in birds) by the absence of Phasianidæ (which are preeminently Indian) and by the presence of Megapodius (which is as preeminently Australian), by having no Trogons, Palæornis or Eurylæmidæ, and by possessing Cacatua, Tanygnathus, and Cyclopsitta. Just in a parallel manner is Celebes distinguished by the presence of peculiar forms of Antelope and Baboon, and by species [[p. 277]] of Sciurus, and, in birds, by having Woodpeckers, Hornbills, and several isolated genera of Passeres, while forms so characteristic of the Austro-Malayan islands as Monarcha, Pachycephala, Tropidorhynchus, and Eos are quite absent. Celebes and the Philippines will therefore form together a little intermediate region between those of Australia and India. The real cause of their distinctive peculiarities I believe to lie in their never having been immediately connected with these regions, though they have probably at some time been in closer proximity than at present--and, in the case of Celebes at least, to their representing the remains of some ancient land extending to the westward, at an epoch probably anterior to that at which Borneo and Sumatra were raised above the ocean. The great islands which form the western half of the archipelago, Borneo, Sumatra, Java, and the Malay peninsula, present a most surprising poverty of Psittacine birds. Only four species are found over this immense region; and these belong to three genera, of which only one is found on both sides of the boundary-line. This fact forms one of the strongest proofs of the division of the archipelago between the Indian and Australian regions; for on the one side we have fifteen genera, of which ten are quite peculiar, on the other three genera, of which one is Indian, one Indo-Australian, and one somewhat isolated species only peculiar. The distribution of the genus Loriculus, which is the only one really common to the Indian and Australian regions, is very interesting. The southern island of the Philippines seems to be its metropolis, since no less than four species are found there; one inhabits Celebes, one Sulla, and one Gilolo; the rest are found in Flores, Java, Sumatra, and Malacca, Ceylon, India, China, and Manilla. The range of the genus is therefore very extensive; yet one-half of the species will be found concentrated in a limited tract, including Mindanao, N. Celebes, Sulla, and Gilolo. This district is upon the confines of the Australian and the Indian regions; and it is very interesting to remark that this, the only genus which is common to the two, is of doubtful affinities, and serves to connect the preeminently Australian Trichoglossidæ with the Psittacidæ of the rest of the world. The classification and natural arrangement of the Psittaci has been the subject of much difference of opinion. For a long time they were placed as a simple family of Scansores along with Woodpeckers, Toucans, and Cuckoos, birds with which it is difficult to see that they have the remotest affinity, and to which they have no resemblance, except in the one character of the 2/2-toed feet. The skull of a Parrot is remarkable for its large size, for the nearly complete orbits, for the broad and powerful lower mandible, for the large and complicated lingual and hyoid bones, and for the perfect articulation of the upper mandible to the cranium--peculiarities which, in their combination, separate it most widely from every other form of bird. The sternum has a characteristic form unlike that of any bird; the furcula is small and attached low down on the anterior margin of the keel, and in some genera is liable to be totally wanting [[p. 278]] in certain species. When present, however, it is of a semioval form, the two branches being connected in an unbroken curve without angle or projecting processes. The prehensile feet of Parrots are used in a manner altogether peculiar; for though other birds may secure their food with their foot while eating, no others in the whole class use it systematically as a hand to grasp and convey food to the mouth. We may fairly say that they are the only birds that have hands and use them as such; and this will serve to confirm the superiority which their large brain and highly organized cranium confers upon them. The presence of a crop, their uniformly fruit-eating habits, their wide distribution, their numerous modifications of form, and their utter dissimilarity to all other birds, added to the differences already pointed out in structure and habits, induce me to adopt without any hesitation the views of Bonaparte and Blyth, and to consider the Parrots as one of the primary divisions or orders in the class of birds. In dividing this order into families I follow generally Bonaparte and Blainville, with a few modifications for simplicity. The great central mass of the order are the Psittacidæ or true Parrots, comprising all the American and more than half the Old-World species. These must be divided into several subfamilies, the Palæornithinæ, the Psittacinæ, and the Eclectinæ, containing the Indian and Malayan species. The next family, the Platycercidæ (the Broadtails and Ground-Parrots), are somewhat allied to the last group through the Palæornithinæ. They have different habits from most other Parrots, being often terrestrial and seed-eaters; their whole structure is weak, their flight slow and Cuckoo-like; the keel of the sternum is lower and more rounded anteriorly than in the other families; the pelvis is short, broad, and flat; the skull is small; the bill short; the lower mandible broad and swollen; the legs rather long and slender; and the plumage lax and abundant. The Plyctolophidæ, or Cockatoos, are distinguished by their powerful bills, crested heads, heavy forms, and lax powdery plumage. They have a general resemblance to the last family and also to the true Psittacidæ. The Trichoglossidæ are the best-marked and most specialized group of all. The whole head, as well as the bill, is elongated and compressed; the wings long and powerful; the feet strongly grasping; and the tongue always furnished with brush-like papillæ. They are connected with the Psittacidæ by means of Loriculus, which agrees with them in general structure, but has the ordinary smooth tongue. In order to bring these families into a natural sequence, I arrange them in the following order:--1. Plyctolophidæ; 2. Platycercidæ; 3. Psittacidæ; 4. Trichoglossidæ. The fifth family, Strigopidæ, containing the New Zealand Owl Parrots, seems allied to the Platycercidæ, and should follow them in a general arrangement of the order. I may here remark that the limits which I place to the Malayan subregion, as distinguished from the Pacific Islands--namely, to include the Solomon Islands, while the New Hebrides and New Caledonia begin the Pacific subregion--is well established by the Psittaci; [[p. 279]] since both the subfamily Loriinæ and the family Plyctolophidæ reach this point only, as well as the truly Malayan genus Geoffroyus. I have endeavoured to make the following list of the Malayan Psittaci as complete and accurate as possible. The localities have been determined from personal observation and inquiry,2 as those usually given are very erroneous, owing to so many of the species being domesticated and carried to every part of the archipelago. Several species, which appear to have been founded on immature birds or accidental variations, are sunk altogether, as well as some which seem to have been described from made-up specimens. A few remarks on the habits of the species observed by myself are also given, and a table showing the geographical range of each species is added. List of the Malayan Species of Parrots. Fam. I. PLYCTOLOPHIDÆ. 1. CACATUA. 1. CACATUA PHILIPPINARUM. Psittacus philippinarum, Gm. Syst. Nat. i. p. 331; Pl. Enl. 191. Hab. Philippine Islands. 2. CACATUA MOLUCCENSIS. Psittacus moluccensis, Gm. Syst. Nat. i. p. 331; Pl. Enl. 498. Hab. Ceram and Amboyna (A. R. W.). 3. CACATUA CRISTATA. Psittacus cristatus, Linn. Syst. Nat. i. p. 143; Pl. Enl. 263; Bourj. Perr. t. 82. Hab. Gilolo, Batchian, and Ternate (A. R. W.). 4. CACATUA CRISTATELLA, n. s. Simillima C. cristatæ, sed multo minor. Exactly like C. cristata in colour, but very much smaller in all its dimensions. It inhabits a limited district in the northern peninsula of Gilolo. The true C. cristata inhabits the other parts of Gilolo; while the specimens from Batchian and Ternate are smaller, but still seem referable to the old species. The following are the comparative dimensions of four specimens in my collection:-- [[p. 280]]

The iris is red in this species, whereas in C. cristata it is dark olive. Hab. Gilolo (Kao) (A. R. W.). 5. CACATUA OPHTHALMICA. Cacatua ophthalmica, Sclat. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1864, p. 188. Hab. Solomon Islands? (Perhaps some adjacent island.) 6. CACATUA DUCORPSII. Cacatua ducorpsii, H. & J. Voy. au Pôle Sud, Zool. i. p. 108, t. 26. f. l; Sclater, P. Z. S. 1864, p. 187, Pl. XVII. Hab. Solomon Islands. 7. CACATUA TRITON. Plyctolophus triton, Temm. Consp. Gen. Ind. Arch. iii. p. 405. Hab. New Guinea (Goram, introduced) (A. R. W.). 8. CACATUA MACROLOPHA. Plyctolophus macrolophus, Bernst. Cab. Journ. 1861, p. 46. Hab. Aru Islands, Mysol, Waigiou, and Salwatty (A. R. W.). 9. CACATUA ÆQUATORIALIS. Plyctolophus æquatorialis, Temm. Consp. Gen. Ind. Arch. iii. p. 405. Hab. Celebes, Flores, and Lombock (A. R. W.). 10. CACATUA SULPHUREA. Psittacus sulphureus, Gm. Syst. Nat. i. p. 330; Pl. Enl. 14; Lear. Parr. pl. 4. Hab. Timor (A. R. W.). 11. CACATUA CITRINO-CRISTATA. Plyctolophus citrino-cristatus, Fr. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1844, p. 38. Hab. Timor-laut. 2. MICROGLOSSUM. 12. MICROGLOSSUM GOLIATH. Psittacus goliath, Kuhl, Consp. Psitt. pp. 9, 94; Levaill. Perr. t. 12, 13. Hab. New Guinea, Waigiou, and Mysol (A. R. W.). 13. MICROGLOSSUM ATERRIMUM. Psittacus aterrimus, Gm.; Kuhl, Consp. Psitt. pp. 12, 91 . Hab. Aru Islands (A. R. W.); N. Australia (B.M.). 3. NASITERNA. 14. NASITERNA PYGMÆA. Psittacus pygmæus, Q. & G. Voy. de l'Astrol. t. 21. f. 1, 2; Wagl. Mon. p. 631. Hab. New Guinea, Mysol (A. R. W.). [[p. 282]] Fam. II. PLATYCERCIDÆ. 4. PLATYCERCUS. 15. PLATYCERCUS VULNERATUS. Platycercus vulneratus, Wagl. Mon. Psitt. p. 533. Hab. Timor (A. R. W.). 16. PLATYCERCUS AMBOINENSIS. Psittacus amboinensis, Bodd.; Briss. Orn. iv. t. 28. f. 2; Linn. Syst. Nat. i. p. 141; Pl. Enl. 240. Hab. Amboina, Ceram, and Bouru (A. R. W.). 17. PLATYCERCUS DORSALIS. Psittacus dorsalis, Q. & G. Voy. de l'Astrol. t. 21. f. 1. Hab. New Guinea, Waigiou (A. R. W.), and Sulla Islands (var.) (Allen). 18. PLATYCERCUS HYPOPHONIUS. Platycercus hypophonius, Müll. & Schleg. Verh. Nat. Gesch. p. 181. Hab. Gilolo (A. R. W.). Fam. III. PSITTACIDÆ. 5. PALÆORNIS. 19. PALÆORNIS LONGICAUDUS. Psittacus longicaudus, Bodd. Pl. Enl. 887. Hab. Malacca, Sumatra, and Borneo (A. R. W.). 20. PALÆORNIS JAVANICUS. Psittacus javanicus, Osb. Hab. Java and Borneo (? borneus, Wagl., immature) (A. R. W.). 21. PALÆORNIS CANICEPS. Palæornis caniceps, Blyth, Journ. As. Soc. Beng. xv. pp. 23, 51, 368. Hab. Nicobar Islands (? Penang). 6. PSITTINUS. 22. PSITTINUS INCERTUS. Psittacus incertus, Shaw, Nat. Miscell. pl. 769. Hab. Malay Peninsula, Singapore, Sumatra, and Borneo (A. R. W.). 7. GEOFFROYUS. 23. GEOFFROYUS PERSONATUS. Psittacus personatus, Shaw, Gen. Zool. viii. p. 544; Lev. Perr. t. 112, 113. Hab. Bouru, Ceram, Amboyna, Goram, Ké Islands (capistratus), Aru Islands (aruensis),

Timor (jukesii), and Flores (jukesii) (A.R.W.). 24. GEOFFROYUS CYANICOLLIS. Psittacus cyanicollis, Müll. & Schleg. Verh. Nat. Gesch. Ethn. pp. 108, 182. Hab. Gilolo and Batchian (A. R. W.). 25. GEOFFROYUS PUCHERANI. Geoffroyus pucherani, Bp.; Souancé, Rev. et Mag. de Zool. 1856, p. 218. Hab. New Guinea, Waigiou, and Mysol (A. R. W.). 26. GEOFFROYUS HETEROCLITUS. Pionus heteroclitus, H. & J. Voy. au Pôle Sud, Zool. iii. p. 103. t. 25*. f. 1. Hab. Solomon Islands. [[p. 284]] 8. PRIONITURUS. 27. PRIONITURUS FLAVICANS. Prioniturus flavicans, Cassin, Proc. Ac. Phil. vi. p. 373 (♀); Sclat. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1860, p. 223 (♂). Hab. North Celebes (Tondano) (A. R. W.). 28. PRIONITURUS SETARIUS. Psittacus setarius, Temm. Pl. Col. 15. Hab. Celebes (Menado and Macassar) (A. R. W.). 29. PRIONITURUS DISCURUS. Prioniturus discurus, Vieill. Gal. des Ois. i. p. 7, pl. 36; Wagl. Mon. p. 524. Hab. Philippine Islands (Mindanao). 30. PRIONITURUS ____. Prioniturus spatuliger (Bourj.), G. R. G. List of Parrots in B. M. p. 18; Sclater, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1860, p. 224. Hab. Philippine Islands. (Probably Mindanao, the island nearest Celebes.) 9. CYCLOPSITTA. 31. CYCLOPSITTA DIOPHTHALMA. Cyclopsitta diophthalma, H. & J. Voy. au Pôle Sud, t. 25 bis, f. 4, 5. Hab. Aru Islands and Mysol (var.) (A. R. W.). 32. CYCLOPSITTA DESMARESTI. Psittacula desmaresti, Garn. Voy. de la Coquille, Zool. t. 35; Bourj. Perr. t. 85. Hab. New Guinea (Dorey Harbour) (A. R. W.). 33. CYCLOPSITTA BLYTHII, n. s. Similis C. desmaresti, sed capite colloque aurantiacis sine macula suboculari cærulea. [[p. 285]] Green; head above deep orange, more intense on the forehead; cheeks and throat pale orange; breast with a band of blue, succeeded by one of brownish orange, as in C. desmaresti; sides of the breast blue; under wing-coverts blue-green; belly yellowish green: bill black; feet greenish olive. Total length 8 inches; wings 4 1/4. 34. CYCLOPSITTA LOXIA. Psittacus loxia, Cuv. Hab. Philippine Islands. 35. CYCLOPSITTA LUNULATA. Psittacus lunulatus, Scop. Sonn. Voy. t. 39. Hab. Philippine Islands (Manilla). 36. CYCLOPSITTA LEUCOPHTHALMA. Psittacus leucophthalmus, Scop. Sonn. Voy. t. 38. Hab. Philippines (Luzon). 10. TANYGNATHUS. 37. TANYGNATHUS LUCIONENSIS. Psittacus lucionensis, Linn.; Briss. Orn. iv. t. 22. f. 2. Hab. Philippine Islands (Manilla). 38. TANYGNATHUS MEGALORHYNCHUS. Psittacus megalorhynchus, Bodd. P. Enl. 713. Hab. Batchian, Makian, Gilolo, Mysol, Waigiou, Sanguir Islands, and New Guinea (A. R. W.). [[p. 286]] 39. TANYGNATHUS AFFINIS. Tanygnathus affinis, Wallace, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1863, p. 20. Hab. Bouru, Amboyna, and Ceram (A. R. W.). 40. TANYGNATHUS MÜLLERI. Psittacus mülleri, Müll. & Schleg.Verh. Nat. Gesch. Ethn. pp.108, 182. Hab. Celebes (Macassar and Menado) (A. R. W.). 41. TANYGNATHUS ALBIROSTRIS. Psittacus sumatranus, Raffl. Linn. Trans, xiii. 281; Wagl. Mon. p. 576. Hab. Celebes and Sulla Islands (A. R. W.). 11. ECLECTUS. 42. ECLECTUS LINNÆI. Eclectus linnæi, Wagl. Mon. p. 571, t. 22. Hab. New Guinea, Mysol, Waigiou, and Aru Islands (A. R. W.). 43. ECLECTUS GRANDIS. Psittacus grandis, Gm. S. N. i. p. 319; Pl. Enl. 683; Wagl. Mon. p. 572. Hab. Gilolo and Batchian (A. R. W.). 44. ECLECTUS CARDINALIS. Psittacus cardinalis, Bodd. Pl. Enl. 518. Hab. Bouru, Amboyna, and Ceram (A. R. W.). 45. ECLECTUS CORNELIA. Eclectus cornelia, Bp. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1849, pl. 11. Hab. Unknown. (Probably either Ceram-laut or Jobie Islands.) 46. ECLECTUS STAVORINI. Psittacus stavorini, Less. Voy. Coq. Zool. p. 628. Hab. Unknown. (Perhaps Jobie Islands or N. Guinea.) 47. ECLECTUS POLYCHLOROS. Psittacus polychloros, Scop. Hab. New Guinea, Mysol, Waigiou, Aru Islands (var.), Gilolo, and Batchian (A. R. W.). [[p. 287]] 48. ECLECTUS INTERMEDIUS. Psittacodis intermedius, Bp. Consp. Gen. Av. p. 4. Hab. Ceram, Amboyna, and Bouru (A. R. W.). 49. ECLECTUS WESTERMANNI. Psittacodis westermanni, Bp. Consp. Gen. Av. p. 4; Proc. Zool. Soc. 1857, p. 226, pl. 127. Hab. Unknown. (Probably New Guinea or Jobie Islands.) 12. DASYPTILUS. 50. DASYPTILUS PEQUETII. Psittacus pequetii, Less. Bull. Univers. 1831, p. 241. Hab. New Guinea and Salwatty. 13. LORICULUS. 51. LORICULUS GALGULUS. Psittacus galgulus, Linn.; Wagl. Mon. p. 626; Pl. Enl. 190. Hab. Malacca, Sumatra, and Borneo (A. R. W.). 52. LORICULUS STIGMATUS. Psittacus stigmatus, Müll. & Schleg. Verh. Nat. Gesh. Ethn. p. 182. Hab. Celebes (Macassar and Menado) (A. R. W.). 53. LORICULUS SCLATERI. Loriculus sclateri, Wall. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1862, p. 336, pl. 38. Hab. Sulla Islands (A. R. W.). 54. LORICULUS AMABILIS. Loriculus amabilis, Wall. Ibis, 1862, p. 349. Hab. Gilolo (A. R. W.). [[p. 288]] 55. LORICULUS PUSILLUS. Loriculus pusillus, G. R. Gray, Brit. Mus. Cat. Psitt. p. 54. Hab. Java (A. R. W.). 56. LORICULUS FLOSCULUS. Loriculus flosculus, Wall. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1863, p. 488. Hab. Flores (A. R. W.). 57. LORICULUS MELANOPTERUS. Psittacus melanopterus, Scop. Sonn. Voy. t. 40. Hab. Philippines (Mindanao). 58. LORICULUS APICALIS. Loriculus apicalis, Souancé, Rev. et Mag. de Zool. 1856, p. 221. Hab. Philippines (Mindanao). 59. LORICULUS BONAPARTEI. Loriculus bonapartei, Souancé, Rev. de Zool. 1856, p. 222. Hab. Sooloo Islands. 60. LORICULUS CULACISSI. Psittacus culacissi, Vieill. Enc. Méth. p. 1405; Wagl. Mon. p. 627. Hab. Philippine Islands. 61. LORICULUS REGULUS. Loriculus regulus, Souancé, Rev. et Mag. de Zool. 1856, p. 222. Hab. Philippines (Mindanao). Fam. IV. TRICHOGLOSSIDÆ. 14. LORIUS. 62. LORIUS DOMICELLA. Psittacus domicella, Linn.; Pl. Enl. 119; Wagl. Mon. p. 567. Hab. Ceram and Amboyna (A. R. W.). 63. LORIUS LORY. Psittacus lory, Linn.; Pl. Enl. 168. Hab. New Guinea, Waigiou, and Mysol (A. R. W.). [[p. 289]] 64. LORIUS CYANAUCHEN. Lorius cyanauchen, Müll. & Schleg. Verh. Nat. Gesch. Ethn. p. 107. Hab. Myfor and Jobie islands (New Guinea). 65. LORIUS GARRULUS. Psittacus garrulus, Linn. Hab. Gilolo and Batchian (A. R. W.). 66. LORIUS CHLOROCERCUS. Lorius chlorocercus, Gould, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1856, p. 137. Hab. Solomon Islands. 67. LORIUS HYPŒNOCHROUS. Lorius hypoinochrous, G. R. Gray, List of Psittacidæ in Brit. Mus. p. 49. Hab. Louisiade archipelago. 15. CHALCOPSITTA. 68. CHALCOPSITTA ATRA. Psittacus ater, Scop. Hab. New Guinea and Mysol (A. R. W.). 69. CHALCOPSITTA SCINTILLATA. Psittacus scintillatus, Temm. Pl. Col. 569 (juv.); Bourj. Perr. t. 51. Hab. New Guinea (Temm.) and Aru Islands (A. R. W.). 70. CHALCOPSITTA RUBIGINOSA. Chalcopsitta rubiginosa, Bp. Consp. Av. p. 3; Proc. Zool. Soc. 1850, pl. 16. Hab. Unknown. [[p. 290]] 16. EOS. 71. EOS INDICA. Psittacus indicus, Gm.; Pl. Enl. 143; Lev. Perr. t. 53. Hab. Siau and Sanguir. 72. EOS CYANOGENIA. Eos cyanogenia, Bp. Consp. Av. p. 4; Proc. Zool. Soc. 1850, pl. 14. Hab. Myfor and Jobie islands (N. of New Guinea). 73. EOS CYANOSTRIATA. Eos cyanostriata, G. R. Gray, Gen. of Birds, ii. pl. 103. Hab. Tenimber Islands and Timor-laut. Remarks.--This species is often brought alive to Macassar in the Bugis praus, which go to the Tenimber Islands for the tripang fishery. 74. EOS RUBRA. Psittacus ruber, Gm. (P. borneus, L.); Pl. Enl. 519; Lev. Perr. t. 44. Hab. Ceram, Goram, Amboyna, and Bouru (A. R. W.). 75. EOS SEMILARVATA. Eos semilarvata, Bp. Consp. Av. p. 4; Proc. Zool. Soc. 1850, pl. 15. Hab. Unknown. (Not Ceram, probably Timor-laut.) 76. EOS SQUAMATA. ? Psittacus squamatus, Bodd. Pl. Enl. 684. Hab. Waigiou (A. R. W.). 77. EOS RICINIATA. Psittacus riciniatus, Bechst.; Lev. Perr. t. 54. Hab. Batchian and Gilolo (A. R. W.). [[p. 291]] 78. EOS FUSCATA. Eos fuscata, Blyth, J. A. S. Bengal, 1858, p. 279. Hab. New Guinea (Dorey) (A. R. W.). 79. EOS UNICOLOR. Psittacus unicolor, Shaw; Lev. Perr. t. 125. Hab. Solomon Islands. 17. TRICHOGLOSSUS. 80. TRICHOGLOSSUS HÆMATODUS. Psittacus hæmatodus, Linn.; Lev. Perr. t. 47; Wagl. Mon. p. 550. Hab. Timor (A. R. W.). 81. TRICHOGLOSSUS FORSTENI. Trichoglossus forsteni, Bp. Consp. Av. p. 8. Hab. Sumbawa (Bonaparte). 82. TRICHOGLOSSUS CYANOGRAMMUS. Trichoglossus cyanogrammus, Wagl. Mon. Psitt. p. 554. Hab. New Guinea, Waigiou, Mysol, Matabello Islands, Goram, Ceram, Amboyna, Bouru,

and Aru Islands (A. R. W.). 83. TRICHOGLOSSUS COCCINEIFRONS. Trichoglossus coccineifrons, G. R. Gray, P. Z. S. 1858, p. 183. Hab. Aru Islands (A. R. W.). 84. TRICHOGLOSSUS ORNATUS. Psittacus ornatus, Linn. Hab. Celebes (A. R. W.). 85. TRICHOGLOSSUS FLAVOVIRIDIS. Trichoglossus flavoviridis, Wallace, Proc. Zool. Soc. 1862, p. 337. Hab. Sulla Islands and ? Celebes (Menado) (A. R. W.). 86. TRICHOGLOSSUS EUTELES. Psittacus euteles, Temm. Pl. Col. 568. Hab. Timor and Flores (A. R. W.). 87. TRICHOGLOSSUS IRIS. Psittacus iris, Temm. Pl. Col. 567. Hab. Timor (A. R. W.). 88. TRICHOGLOSSUS MASSENA. Trichoglossus massena, Bp. Rev. et Mag. de Zool. 1854, p. 157. Hab. Solomon Islands. 18. CHARMOSYNA. 89. Charmosyna papuensis. Psittacus papuensis, Gm. (japonicus, L.). Hab. New Guinea (A. R. W.). 90. CHARMOSYNA PULCHELLA. Charmosyna pulchella, G. R. Gray, List of Psitt. in B. M. p. 102. Hab. New Guinea (Dorey) (A. R. W.). 91. CHARMOSYNA PLACENTIS. Psittacus placentis, Temm. Pl. Col. 553. Hab. Batchian and Gilolo (A. R. W.). Var. a. With less red on throat. Hab. Ceram (A. R. W.). Var. b. With scarcely any red on throat. Hab. Aru Islands (A. R. W.). [[p. 293]] 92. CHARMOSYNA RUBRONOTATA. Coriphilus rubronotatus, Wall. Proc. Zool. Soc. 1862, p. 165. Hab. Salwatty (A. R. W.).

1. The red line on the accompanying map encloses the area to which the crimson Lories are restricted. [[on p. 274]] 2. N.B. The initials (A. R. W.) after any locality show that the species was observed there by myself. [[on p. 279]]

|