|

Russel Wallace : Alfred Russell Wallace (sic) with New Guinea and Its Islands (S65: 1862)

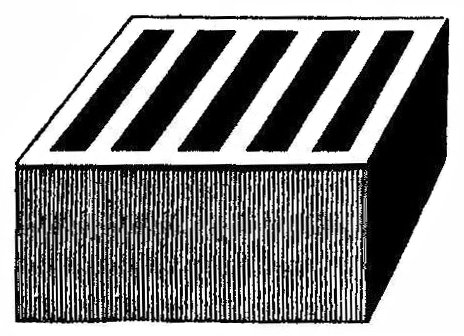

The only articles of commercial value procured from the interior of New Guinea are Mussoi bark and wild nutmegs. From the coasts and islands tripang or bêche-de-mer, mother-of-pearl shell, and tortoise-shell are all produced in abundance; and as they are all articles which command a ready sale, and at high prices, the trade is a very important one. The articles of less importance are pearls, birds of Paradise, sago (raw and in cakes), mats, palm-leaf boxes, and rice in the husk, or paddy. The destination of these articles is various, and but few reach Europe. The Mussoi bark, which contains an aromatic oil of a rather pungent odour, is sent to Java, where the natives buy it at a high price to rub on the skin as a remedy for rheumatic and many other diseases. It is probably from a tree of the cinnamon family. The tripang or sea-slug is all bought up by the Chinese, who are the only consumers of this repulsive article. The tortoise-shell is mostly bought by the Manilla traders, and I presume much of it is manufactured in the Philippines into combs and ornaments. Finely-spotted shells with much white in them are very highly esteemed, and command high prices. These the richer natives often keep in their houses as ornaments, and as articles always convertible into cash. Some tons of tortoise-shell must be produced annually on the coasts of New Guinea, and, as it is worth here 12s. to 20s. per pound, it becomes of itself an important trade. The pearl-shell and the wild nutmegs go all to European markets. Of the less important articles, the birds of Paradise are dispersed over the world; the greater part, I believe, now go to China. The pearls--which are few, and seldom fine--are also mostly bought by the Chinese. The sago and rice being very local productions, and the former being the staple food of the [[p. 128]] surrounding districts, they are a great medium of exchange over all the Papuan countries, a little being also taken to Ternate. The mats and palm-leaf boxes are in great demand all over the Moluccas. The goods with which these various products are purchased are not very diversified, the principal being bar-iron, calico, and thin red cottons from England, choppers made in Singapore or Macassar, Bugis cloths, cheap German knives and Chinese plates and basins, brass-wire, white and coloured beads, and silver coins. Arrack is indispensable in some districts, opium in others; but these are not in such general demand as the preceding. The trade is mainly carried on in native prahuws, a few small schooners only being now engaged in it from Ternate, Menado, Amboyna, and Macassar. They, however, form quite an unimportant feature in the trade of New Guinea, which is essentially native. A Malay prahuw is a vessel so unique as to deserve a brief description. It is a short vessel with bow and stern nearly alike. The deck (when it has one) slopes down towards the bows. The mast is a triangle, and consequently wants no shrouds, and, being low, carries an immense yard much longer than the vessel itself, which is hung out of the centre, and the short end hauled down on deck, so that the immense mainsail slopes upwards to a considerable height. A full-rigged prahuw carries a smaller similar sail abaft, and a bowsprit and jib. It has two rudders, one on each quarter, with a window or opening on each side for the tillers considerably below the deck. These vessels can only sail 8 points from the wind (so that it is impossible to make any way by tacking when the wind is ahead), and make their voyages only with the favourable monsoon--accomplishing, therefore, generally but one voyage a year. They are of all sizes, from l to 100 tons' burden, and are built--some with regularly nailed planks, some fastened only with rattans--but so ingeniously and securely as very well to stand a sea-voyage. When I first went from Macassar to New Guinea, a distance of 1000 miles, a small prahuw of about 10 tons which had not a single nail in its whole structure kept company with us all the way. The largest prahuws are from Macassar and the Bugis countries of Celebes and the island of Boutong. Smaller ones in great numbers sail from Ternate, Pidore, East Ceram, and Goram, which I shall have occasion again to allude to. I will now give a short notice of the chief districts of New Guinea and its islands, with the most important particulars relating to the trade carried on there, and the condition and character of the inhabitants. Great Geelvink Bay.--The centres of trade for this district are [[p. 129]] Dorey and the little island of Roen. The inhabitants of the mainland and of the island of Jobie are very ferocious. At Jobie vessels at anchor have been attacked, and sailors on shore have been frequently murdered. A schooner from Ternate comes every year to Roen and the district of Wandamen, at the head of the bay, to load Mussoi bark, which is found here only. One or two prahuws from Ternate also go along the coast of Jobie and round the bay, buying tortoise-shell and tripang. The natives of Dorey, in small boats, visit Mafor, Sook, and Biak, and the west end of Jobie, buying tortoise-shell, birds of Paradise, and crown-pigeons, which they sell to the traders who touch at Dorey. The inhabitants of Dorey, Roen, and some of the other coast villages have a little sprinkling of Malay blood, are beginning to use clothing, and thus make the first step in civilization. Jobie is celebrated for its birds of Paradise, the only product of its interior. Dorey produces rice, which the natives take to Salwátty and exchange for sago. The Dorey people also go to Amberbaki, 100 miles westward, to buy vegetables and birds of Paradise, for which that village is celebrated. Salwátty and Waigioú.--Salwátty is a great sago country, supplying all the neighbouring districts with this necessary of life. It is the centre of the trade of the western extremity of New Guinea, a Bugis trader having an establishment in the chief village of Semeter, and most of the trading prahuws and schooners touching there. Tortoise-shells, pearl-shell, and tripang are produced in great abundance on the shoals and islands round about, and the coast of New Guinea to the eastward produces the greatest number and variety of birds of Paradise. Waigioú possesses but few inhabitants, and no true indigenes. It is remarkable for its deep inlets and narrow, rocky channels, but imperfectly represented on the charts. The village of Waigioú is situated at the head of the deepest inlet, and, being the only part of the island producing sago, is much resorted to. Pearl-shell is also found there. The productions of Waigioú are taken either to Salwátty or to Tidore, few trading prahuws visiting it. The inhabitants of all this part of New Guinea may be divided into two classes: the coast people, who have more or less mixture of Malay blood, are mostly nominal Mahometans, build their houses on stakes in the water, and occupy themselves almost entirely with fishing; and, secondly, the inland people, commonly known as Alfurus, who are of more pure Papuan blood, live on the mountains, cultivate vegetables, and catch birds of Paradise. They are considered as inferiors, and almost as slaves, by the coast people, and have in almost every district a distinct language, while the coast people from Dorey and the islands of the Great Geelvink Bay to Salwátty, [[p. 130]] Waigioú, and Mysol, all speak the same language--or so nearly the same that they can understand one another. In their villages one always finds some people who can speak Malay, which is generally quite unknown to the Alfurus. The inhabitants of Waigioú have slaves who cultivate their vegetable grounds, but they have been originally brought from the mainland of New Guinea, and are not true indigenes. They now speak the same language as the coast people. The districts south-east of Salwátty and the coasts of McLuer Inlet produce abundance of wild nutmegs, and a schooner comes annually from Ternate, and generally obtains a full cargo of them. The natives of this part are dangerous. Mysol or Misool.--This island produces a great deal of sago and Mussoi bark, and abundance of tripang, with tortoise-shell, pearls, and birds of Paradise. A number of Goram and Ceram prahuws visit it annually to load sago, which they take to Ternate. The largest village is Lilinta, on the south coast, in the chief sago district. The inhabitants of the coast are Mahometans, governed by native rajahs, and speaking the common North Papuan language. In the interior are true indigenes, having a very distinct language. This island is mountainous, but not very lofty. The rocks are sandstones and limestones. One of the latter much resembles hard chalk, and contains flints and belemnites. If geologically contemporaneous with the Cretaceous formation, it is the only instance I am acquainted with of true secondary strata occurring in the Moluccas or New Guinea. I have before only met with highly crystalline rocks, volcanic, coralline, or alluvial formations. Coast South of McLuer Inlet.--The peninsula south of McLuer Inlet is known to the native traders by the name of Papua Onen. The people of Goram chiefly trade there; but the natives are very treacherous, and, when not satisfied with the barter offered them, will frequently attack and murder the traders. On the coast are a few villages of Mahometans, who are also subject to constant attacks of the indigenes of the interior. The productions are wild nutmegs and Mussoi bark, in small quantities, with the usual tortoise-shell and tripang on the coasts. Farther south from Adie Island to Utanáta is the Papua Kowiyeí of the traders. The Goram and Bugis traders have almost the monopoly of this district, which produces much Mussoi bark, with the other usual products, and is celebrated for the number of lories, cockatoos, and other birds procured there. Even these are not of trifling value, as every prahuw returning from any part of New Guinea is sure to bring some dozens or scores of them, and they all sell readily in the ports of the Moluccas at from 2s. to 10s. each, or even more. Many hundreds--I might perhaps say [[p. 131]] thousands--are brought from the Papuan countries every season, yet the supply seems never equal to the demand. The natives of many parts of this coast are also very dangerous. While I was at Goram (in May, 1860), the crews of two prahuws, including the Rajah's son, were attacked in this part of New Guinea, in open day, while bargaining for some tripang, and all murdered except three or four, who escaped in a small boat and brought the news. The shrieks and lamentation in the village when the news was brought were most distressing, almost every house having lost a relation or a slave. Farther east than Uta, as well as the eastern parts of the Geelvink Bay, go by the name of Papua Talanjong, or "Naked Papua," because the natives are absolutely without clothing, or any apology for it. These parts, however, are seldom visited. The Aru Islands.--Of all parts of the New Guinea district, the Aru Islands are the most productive. Ten or twelve of the largest-sized Macassar and Bugis prahuws go there annually, and generally get a full cargo of pearl-shell, tripang, and tortoise-shell. Besides these, scores of smaller boats flock there from Goram, East Ceram, Banda, and Amboyna; while the natives of Ké, of Temimber, of Babber, and of some parts of New Guinea, come there as to a fair to dispose of their products, or to fish for the supply of the traders. The village of Dobbo, on one of the western islands, is the centre of the trade, where the large prahuws are hauled up and repaired, smaller ones being sent among the islands to collect produce. The village is situated on a narrow spit of sand, on which are crowded three streets of rude thatched houses, while a larger population live in their boats or under mats on the beach. In the height of the season I calculated that Dobbo contained 1000 inhabitants--some from almost every chief island in the Archipelago. Chinamen from Macassar opened stores, tempting the motley population with gaudy china, glass, and trinkets. Even the European luxuries of sugar, biscuit, preserved fruits, and wine, were to be obtained in small quantities, but at very moderate prices, and there was generally no advance made on the Singapore or Macassar rates, the dealers trusting to the profit obtained on the produce taken in exchange from the native buyers. Cockfighting and football-playing (in which the Bugis are very expert) took place almost every evening in the widest part of the street; and though quarrels sometimes occur and creeses are drawn and used, yet, considering there is no government, and the mixture of races and religions crowded together, all eager for gain, order and harmony generally prevail. This is in part due, however, to a Dutch official, who makes an annual visit for a few days to hear and decide disputes and punish offences. Aru is one of the places in which arrack is indispensable to [[p. 132]] purchase produce. A native who has accumulated a good lot of tripang or pearl-shell, besides the cloth, crockery, and ironware, will always have one or two cases of arrack (of about 7 gallons each) in payment. He then calls together his particular friends and has a grand drinking bout, which continues day and night till the whole is finished. During these orgies they frequently break or burn half their scanty moveables, or even pull their own house down about their ears, of course fighting occasionally; but, as the women remove all weapons, lives are seldom lost. The natives with whom I resided in the interior boasted of these exploits, saying they did not do things by halves, and that they would rather have no arrack at all than not enough to get thoroughly well drunk while they were about it. Owing to the great competition in Aru, articles are sold very cheap, and a high price given for all native produce. It thus happens that these remote and savage islanders obtain calicoes, handkerchiefs, and other articles, which are to them more ornament than clothing, at a far cheaper rate (estimated in labour) than the inhabitants of the towns where they are made, or the workmen who produce them. This is one of the anomalous results of that immense commercial and manufacturing system of which we are so proud, and whose continual increase we look upon as an unmixed blessing to mankind. The trade of Aru is perhaps more considerable than that of any other part of the Papuan district. In the year 1857, when I visited the islands, there were 15 large prahuws from Macassar, and more than 100 small ones, of various sizes, from Ceram, Goram, and the Ké Islands. The Macassar cargoes were worth about 200,000 rupees (15,000 l.), and the small boats about 50,000 rupees more. The great bulk of this consists of pearl-shell and tripang, all other articles of produce being in much smaller quantities. The Goram and Ceram men bring cargoes of sago-cakes, which the natives of Aru eagerly buy; and there are many natives of the island of Babber who devote themselves to fishing, while the inhabitants of the interior bring large quantities of sugar-cane, plantains, and other vegetables. Dobbo, therefore, is well supplied with provisions, and is on that account a much more agreeable residence than any other part of the Papuan district, where provisions are very scarce, and the obtaining anything to eat is a daily-recurring problem. Several of the villages of Aru are Christian, and have native schoolmasters from Amboyna: others are Mahometan; while the natives of the interior have nothing that can be called a religion. As is generally the case in the far east, the latter are the most industrious of the three, and are therefore the least miserable, and by far the most pleasant to reside with. [[p. 133]] Ké Islands.--The natives of Ké are the boat-builders of the far east. Several villages are constantly employed in this work, in which they are unequalled in the Archipelago. Their forests produce excellent timber of many different kinds; and the workmen are so expert in the use of the axe and adze, that with these alone they produce vessels of admirable form and most excellent workmanship. In a good Ké prahuw the model is perfect; the planks are as smooth as if planed, and fit together so exactly that from end to end a knife cannot be inserted between them. The planks are all cut out of the solid wood, with a series of projections left on the inside, to which the inner timbers are attached by rattans. The planks are all pegged together along the edges with pins of hard wood, so that it is impossible they can spring. After the first year the rattan-tied ribs are generally replaced by new ones, fitted to the planks and nailed, and the vessel then becomes fully equal to those of the best European workmanship. The Papuan traders and the natives of Goram and Ceram all buy their prahuws and small boats at Ké, and lately several fine schooners have been built there. Very excellent ship-building timber may be purchased here at cheap rates--muskets, gongs, and cotton cloths being the principal articles taken in exchange: good carpenters' tools are also much appreciated. Besides boats and timber, cocoa-nut oil is the chief export of the Ké Islands. The original inhabitants of Banda have emigrated to Ké since the Dutch took possession of that island, and they now inhabit separate villages, having preserved their language, and are known as Ké Banda people. Between Ké and Ceram are a range of islands, inhabited by natives of Papuan race, but becoming lighter in colour as we approach Ceram. About midway is Teor, a small hilly island inhabited by a fine race of brown-skinned frizzly-haired people, who cultivate vegetables and seek tortoiseshell, which they bring in their little open boats to Goram and Ceram. The Matabello Islands are raised coral reefs, 300 to 400 feet high, covered with fruit-trees and cocoa-nuts, from which the natives' manufacture oil, which is the principal article of trade. They are wealthy, the women all wearing massive gold earrings, and the chiefs dressing on state occasions in flowered satin gowns and scarfs. In their villages, too, are dozens of small brass guns, which must have cost a great deal of money; yet their houses are most miserable and filthy, and their food most precarious and scanty. Cocoa-nuts and oil-refuse, with an occasional sago-cake, form their principal subsistence, and cutaneous diseases, as the necessary result, everywhere abound. A little farther to the north-west is the Goram group, consisting of three islands, and very thickly inhabited by a race allied to the Ceram Malays. They are the great traders of the far east, visiting all the coasts and islands of New Guinea, and selling the product [[p. 134]] of their voyages to the Bugis and Chinese traders, who have their general "rendezvous" at Kilwaru, in the Ceram Laut Islands. In their voyages they are most enterprising; in other respects very inactive and lazy, depending for food almost entirely on the labours of their Papuan slaves. Many of the inhabitants are much addicted to opium-smoking. The only manufactures of Goram are coarse mat sail-cloth, a little cotton, and ornamental boxes made of sago-pith and pandanus-leaves, which are much esteemed all over the Moluccas as clothes-boxes. The Goram men visit Banda, Amboyna, and Ternate; but seldom extend their voyages farther, as the Bugis traders give them a good price for their tripang and tortoise-shell. The great "rendezvous" for the New Guinea traders is Kilwaru, a little island scarcely 50 yards across, situated between Ceram-laut and Keffing. On both sides of it is a good anchorage in all weathers, which is probably the reason why it has been chosen. Though scarcely raised above high-water mark, and with not two acres of surface, it possesses wells of very good drinking water--a fact which I could hardly have believed had I not examined it myself. When I visited Kilwaru there were a native schooner from Baly, and several Chinese and Bugis prahuws from Macassar, in the harbour; and there were stores open on shore, in which almost every article requisite for New Guinea trade could be procured. Sugar, tea, coffee, rice, arrack, and wine were also to be purchased here, and a large assortment of cotton-cloths, both of European and native manufacture, as well as muskets, gunpowder, china, crockery, German knives, opium, and tobacco. Sago being so intimately connected with the trade of New Guinea, and forming the staff of life for so large a portion of the natives engaged in it, a short account of its growth and manufacture may be appropriately given. The sago-tree is a palm, thicker than the cocoa-nut-tree, but not so tall, with immense spiny leaves, which completely cover the stem till it has arrived at a considerable age, when the lower ones rot and fall off, leaving the bare stem. It has a creeping root, or rhizoma, like the Nipa palm, and bears an immense terminal spike of flowers at about ten or fifteen years of age, after which the tree dies, being thus allied to our annual and biennial plants, and to the aloe. It grows in swamps or in swampy hollows on the rocky slopes of hills, where it appears to thrive equally well as when exposed to the daily influence of salt or brackish water. The midribs of the leaves form one of the most useful products of these lands, supplying the place of bamboo, to which, for many purposes, they are superior. These midribs are 12 or 15 feet long, and often as thick as one's leg at the base. They are very light, consisting entirely of a firm pith, covered with a hard brown [[p. 135]] skin. Entire houses are built with them. They form admirable roofing poles for thatch; split and well supported, they make flooring; and when chosen of equal size and pegged together, they form excellent walls and partitions to framed wooden houses; carefully split and shaved smooth, they are formed into boards, with pegs cut out of the hard skin, and are the foundation of the leaf-covered boxes of Goram and New Guinea. All the insect-boxes I have used in the Moluccas are thus made in Amboyna; and when covered with paper inside and out are quite strong enough, exceedingly light, and carry insect pins remarkably well. The leaflets of the sago folded and tied side by side on the smaller midribs, or to strips of bamboo, form the "attap," or thatch, in universal use; while the product of the stem is the daily food of some hundred thousands of men. When sago is to be made, a full-grown tree is cut down and cleared of leaves, and a broad strip of bark on the upper side is taken off, exposing the pith, which is of a rusty colour near the base, but pure white higher up, as firm as a dry potato, but with woody fibres running through the substance and branching in every direction, about a quarter of an inch apart. The pith is beaten into powder by means of a hard and heavy piece of wood, with a bit of quartz or flint fixed into the end. At each blow this cuts away a narrow strip of pith, which falls down into the hollow cylinder formed by the trunk, and is packed into baskets, made of the sheathing bases of the leaves. It is then carried to the nearest water, when a washing-machine is constructed, composed entirely of the tree itself, with strainers of the cloth-like sheaths of the cocoa-nut leaves. Successive washings dissolve and carry away all the starchy matter, which settles in large hollows formed in the water-troughs. This is packed cylindrically in sago-leaves, and is the raw sago of commerce. Raw sago, simply boiled with a little water, forms a thick starchy mass, called "papéda," eaten with chop-sticks, in the Chinese fashion. More commonly, however, it is baked into cakes, in small clay ovens, containing six or eight vertical slits, side by side, about three-quarters of an inch wide, and forming cakes six or eight inches square. This is thoroughly heated over a clear fire, and the

sago, first dried, powdered, and finely sifted, is filled into it. It is covered with a piece of flat sago-bark for a few minutes, and the cakes are baked. The hot cakes, with the addition of a little sugar or grated cocoa-nut, are very agreeable, something resembling maize-bread. When required to be kept, however, they are dried for [[p. 136]] several days in the sun, and tied in bundles, of 20 to 50 each, when they can be kept for years. When thus dried they are very hard, and taste rough, like sawdust-bread; but the people are used to them from infancy, and little children may be seen gnawing them as contentedly as our own with their bread and butter. It is truly an extraordinary sight to see a whole tree-trunk, perhaps 20 feet long, and 5 in circumference, converted into food, and with no more preparation or labour than is required to make flour from wheat or maize. A good-sized tree will produce 30 tomans, or bundles of 30 lbs. each; and these when baked will give 60 cakes, of 3 to the pound. Two of these cakes are a meal for a man, or about 5 a day; so that, reckoning a tree to produce 1800 cakes, weighing 600 lbs., it is food for one man for a year. The labour to produce this is as follows:--Two men working moderately will finish a tree in five days, and two women will bake the whole in about five days more; but the raw sago can be kept any time, and baked as wanted, so that we may estimate that in ten days a man may produce food for the whole year. This is, however, if he possesses trees of his own, for all are now private property, and poor men have to buy a tree for 5 or 6 rupees (about 9s.). The ordinary price of labour here is 25 doits, or 4d., a day; so that the total cost of 1800 cakes, or a year's food for one man, is about 12s. This excessive cheapness of food is, contrary to what might be expected, a curse rather than a blessing. It leads to great laziness and the extreme of misery. The habit of industry not being acquired by stern necessity, all labour is distasteful, and the sago-eaters have, as a general rule, the most miserable of huts and the scantiest of clothing. In the western islands of the Archipelago, where rice is the common food of the people, and where some kind of regular labour is necessary for its cultivation, there is an immediate advance in comfort, and a step upward in civilization. This limited observation may be extended with the same results over the whole world; for it is certainly a singular fact that no civilized nation has arisen within the tropics. That rigour of nature which some may have thought a defect of our northern climes has, under this view, been one of the acting causes in the production of our high civilization. We may, indeed, further venture to suppose that, had the earth everywhere presented the same perennial verdure that exists in the equatorial regions, and everywhere produced spontaneously sufficient for the supply of men's physical wants, the human race might have remained for a far longer period in that low state of civilization in which we still find the inhabitants of the fertile islands of the Moluccas and New Guinea. These scanty notes on the commerce of a very remote and little- [[p. 137]] known region have been collected during three voyages to various parts of New Guinea and its islands. They are offered to the Royal Geographical Society in the belief that no authentic and connected information on the subject has yet been published, and with the hope that their crudeness and deficiencies will be pardoned.

|