Khanuy Valley

|

Initial work in the Khanuy Valley region of northcentral Mongolia set the stage for much of the research that came after. It consisted in a proxemic analysis of Bronze Age communal ritual and mortuary monuments and the construction of place within a mobile pastoralist system. This early spatial and archaeological evidence indicated that ritual was probably important for supra-local integration in the absence of everyday face-to-face interaction and an important vehicle of political advancement (Houle 2009).

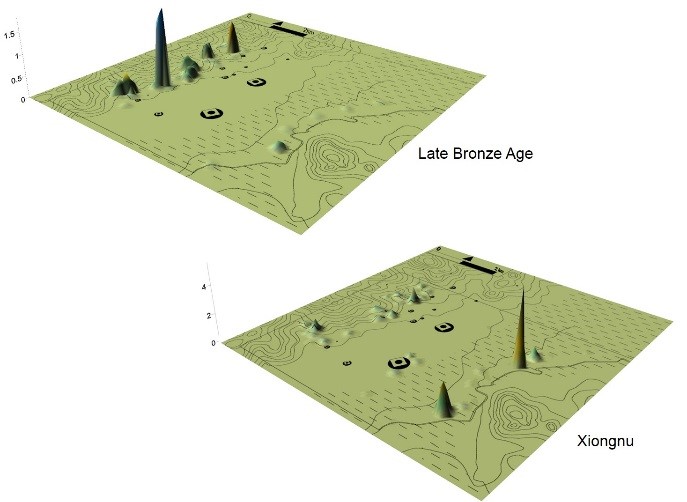

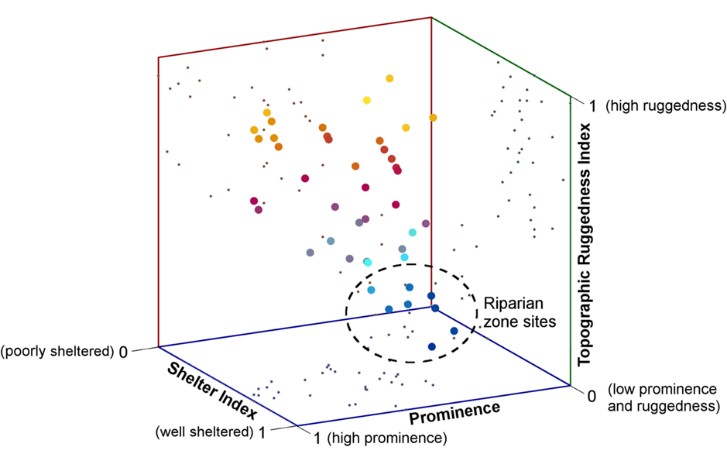

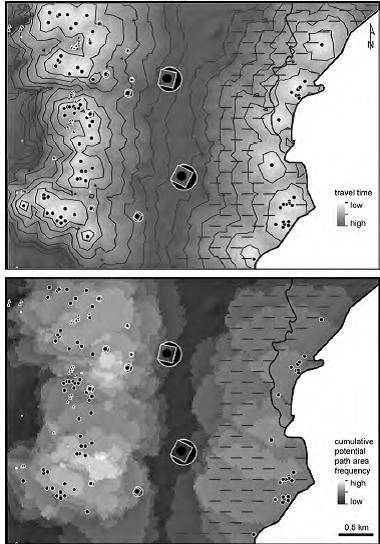

Following this, we engaged in a regional and subregional scale project that focused on investigating the early development of societal complexity in Khanuy Valley by empirically testing the ‘dependency’ hypothesis of sociopolitical development among mobile pastoralists of the Late Bronze Age (mid-2nd to mid-1st millennia BCE)—a long-held core-periphery issue that contends that the development of complex social organization among ‘nomadic pastoralists’ depends upon and requires interaction with already existing agricultural state-level societies. This research included multiscalar spatial analysis, excavations of habitation sites, demographic reconstruction, palaeoenvironmental studies, and materials analysis. The results of this research has upended some of the ideas tied to the dependency hypothesis and suggest that the initial development of complex social organization in this region arose as the result of indigenous political processes and not from the influence of large sedentary states such as those found in China at the time (Houle 2010). We also investigated subsistence strategies, dietary breadth, and mobility patterns in Bronze Age Mongolia. Until recently, knowledge of subsistence strategies, dietary breadth, and mobility in Bronze Age Mongolia was hampered by a monument focused research paradigm, which had largely ignored habitation sites. Analysis revealed a complex subsistence strategy focused on the herding of several species of domestic animal, with dietary breadth increased through the minimal exploitation of wild resources (Broderick and Houle 2012; Broderick et al. 2014). Results also revealed a very restricted mobility pattern during the Late Bronze Age – one that resembles very much ethnohistoric and ethnographic patterns (Houle 2016). Research then built on this regional and subregional data and focused attention at the household level of analysis. This research comprised a specialized and complementary suite of analytical strategies that included excavations of habitation sites, as well as the use of zooarchaeology, palaeobotany and geoarchaeology (including new archaeometric methods) in order to evaluate continuity and change in the range, organization and variation of household activities as the region was incorporated into the Xiongnu Empire (300 BCE – 200 CE)—the first state-like ‘nomadic’ polity to develop in the Eurasian steppe region. The objective of this research was to find out if and how mobile pastoralist households responded to and participated in the broader political and economic system. Results indicate that social organization remained relatively “egalitarian” and autonomous at the local level and hierarchical and integrated at the regional level (Houle n/d; Houle and Broderick 2011). Additional work focused on the relations between Late Bronze Age domestic and monumental sites in Khanuy Valley through GIS analyses of past mobility and accessibility patterns and the potential uses of time-geography. In our Khanuy Valley case study the imposing monumental landscape seems to have ordered and channeled the seasonal mobility pattern(s) on the local level. Distance from and inter-visibility with different kinds of sites seems to have affected the placement of both the settlement and monumental sites in the landscape, besides more practical environmental and economic aspects connected to settlement site placing, such as topography and livelihood constraints. It also seems possible that monuments affected mobility on a wider level, perhaps for seasonal gatherings for communal celebrations at sites such as the largest khirigsuurs, which demonstrably exhibit labor input beyond the scope of a local social unit. Khirigsuur clusters in the Khanuy Valley are situated within reasonable horseback travel distance from each other, and from the largest khirigsuurs. Also the valleys to the east and west are reachable through the mountain passes within a comparable time-budget, so correspondingly these areas might have formed part of the same supra-local social network. Perhaps the foundations of social complexity, observable in the following Iron Age times, lies in developments during the late Bronze Age, such as the possible establishment of hereditary spiritual or political leadership status and supra-local social ranking (Seitsonen et al. 2014). |