The West

The East mainly Japan

- The West

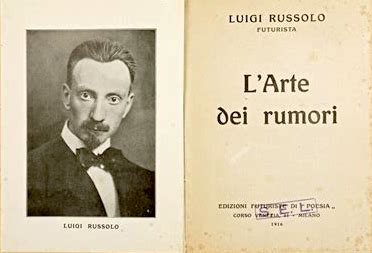

- Luigi Russolo (1885 – 1947)

- Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo proposed the idea that urban and industrial sounds, including the noises of modern warfare, were a new and enthralling source of musical material.

- Russolo argues that the human ear has become accustomed to the speed, energy, and noise of the urban industrial soundscape; furthermore, this new sonic palette requires a new approach to musical instrumentation and composition.

- He proposes a number of conclusions about how electronics and technology will allow futurist musicians to substitute for the limited variety of timbres that the orchestra possesses to the infinite variety of timbres in noises, reproduced with appropriate mechanisms.

- He devised ways in which to reproduce noise with mechanical instruments, bringing a likeness of "the sounds of the street and factories" into the concert hall.

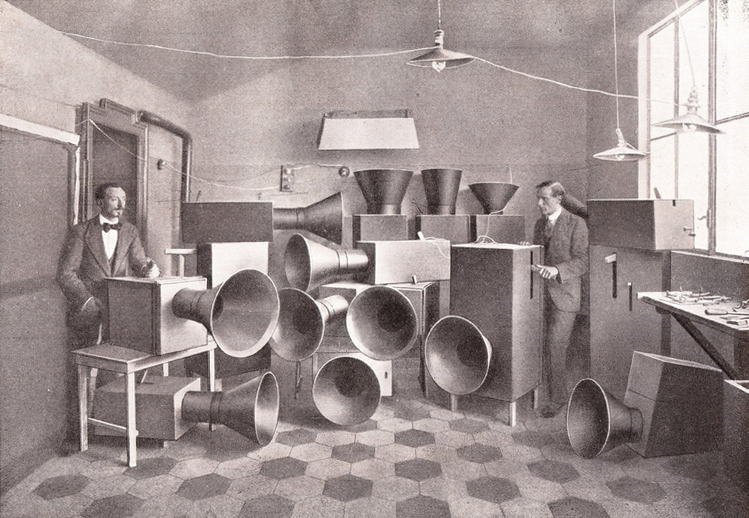

Intonarumori by Russolo

- The first public appearance of the intonarumori took place in 1913 at Modena’s Teatro Storchi.

- In 1914 he took concerts in Milan, Genoa and London. In 1921, after WWI, he presented three concerts in Paris and, in 1922, participated in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s play Il tamburo di fuoco with some musical backgrounds made with the intonarumori.

Intonarumori orchestra, Paris 1921.

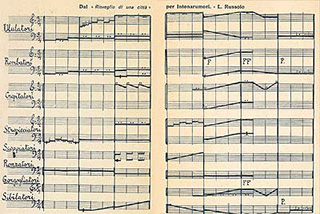

Enharmonic notation for intonarumori by Luigi Russolo

- Later, John Cage would speculate on the beauty of noise and eventually pipe live sounds of the street and bars into the concert hall in 1965.

- These sentiments have been appreciated and put into practice by many sound artists. There have never been any rules for how best to bring the environment into sound art.

- Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo proposed the idea that urban and industrial sounds, including the noises of modern warfare, were a new and enthralling source of musical material.

- The Art of Noises

- Luigi Russolo designed and constructed a number of noise-generating devices called Intonarumori and wrote a manifesto titled The Art of Noises that is considered to be one of the most important and influential texts in 20th-century musical aesthetics.

- Russolo's essay explores the origins of man made sounds.

"Ancient life was all silence. "noise" first came into existence as the result of 19th century machines.

Before this time the world was a quiet place, if not silent with the exception of storms, waterfalls, and tectonic activity..."

"The earliest 'music' was very simple and was created with very simple instruments.

While it tried to create sweet and pure sounds, it progressively grew more and more complex, with musicians seeking to create new and more dissonant chords.

This comes ever closer to the "noise-sound" of noise music."

- He notes that our once desolate sound environment has become increasingly filled with the noise of machines, encouraging musicians to seek greater variety in timbres and tone colors and to create a more "complicated polyphony" in order to provoke emotion and stir our sensibilities. He says that

"We must break out of this limited circle of sound and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds, and that technology would allow us to manipulate noises in ways that could not have been done with earlier instruments."

- Future sounds Russolo claims that

"Music has reached a point that no longer has the power to excite or inspire.

Even when it is new, it still sounds old and familiar, leaving the audience waiting for the extraordinary sensation that never comes."

- He urges musicians to explore the "city with ears" more sensitive than eyes, listening to the wide array of noises that are often taken for granted, yet (potentially) musical in nature.

- He feels this noise music can be given pitch and regulated 'harmonically', while still preserving irregularity and character, even if it requires assigning multiple pitches to certain noises.

- Luigi Russolo designed and constructed a number of noise-generating devices called Intonarumori and wrote a manifesto titled The Art of Noises that is considered to be one of the most important and influential texts in 20th-century musical aesthetics.

- The East mainly Japan

- Group Ongaku

- In 1958, some students from Tokyo National University of Fine Art and Music, including Takehisa Kosugi and Yasunao Tone, conducted a musical experiment with ideas akin to Avant-guard Fluxus artists and Western composer, John Cage.

- The students named themselves Group Ongaku and released music which was highly experimental with industrial timbres.

- Group Ongaku's aim was to re-evaluate improvisational elements in music, which had been lost in Western music since the Baroque era; its members sought to rediscover the meaning of music.

- While the sounds hadn’t reached the sheer intensity of acts that spawned in the late 1970’s, the improvised white noise of the hoover, gut-wrenching screams, echoed radio bleeps show the seeds of 'noise' germinating.

- Despite only being able to listen to a one-hour-long record of theirs now, they played throughout the 1960s at events with performance artists like Yoko Ono.

- This ties into the art world with obscure live acts would continue into the noise tradition that would later manifest in Japan.

- In 1958, some students from Tokyo National University of Fine Art and Music, including Takehisa Kosugi and Yasunao Tone, conducted a musical experiment with ideas akin to Avant-guard Fluxus artists and Western composer, John Cage.

- Japanoise: the noise music scene of Japan.

- Merzbow (メルツバウ) is a Japanese noise project started in 1979 by Masami Akita, best known for a style of harsh, confrontational noise.

- The name Merzbow comes from the German dada artist Kurt Schwitters' artwork Merzbau, in which Schwitters transformed the interior of his house using found objects. The name was chosen to reflect Akita's dada influence and junk art aesthetic.

- Since 1980, Akita has released over 400 recordings and has collaborated with various artists.

- Hijokaidan (非常階段, emergency staircase) is a Japanese noise and free improvisation group. It began in 1970s as a performance art-based group whose anarchic shows would often involve destruction of venues and audio equipment.

- Incapacitants is a Japanese noise music group formed in 1981. They aim to produce "pure noise", uninfluenced by musical ideas or even human intention.

- Paul Hegarty is best known as the author of Noise/Music: A History (2007).

"In many ways it only makes sense to talk of noise music since the advent of various types of noise produced in Japanese music, .... With the vast growth of Japanese noise, finally, noise music becomes a genre".

- We Don't Care About Music Anyway (2009) by Cédric Dupire and Gaspard Kuentz

- The documentary foregrounds six of Japan’s most innovative musicians who are working on the fringes of culture, blurring the lines between music and noise.

- The amplified sound of a controlled heartbeat, the screech of an electric cello played with ferocity turntablism at its most extreme: these are the sounds of Tokyo’s world renowned avant-garde music scene.

- Their sounds are played out against the backdrop of a diverse cityscape, from desolate junkyards and monolithic warehouse spaces to overpopulated intersections, in a frenetic, choreographed montage that dizzies the mind and cranks up the heart.

- Rebelling against ancient traditions, these revolutionary artists demonstrate the evolutionary nature of culture.

Hiromichi Sakamoto

Otomo Yoshihide

- Merzbow (メルツバウ) is a Japanese noise project started in 1979 by Masami Akita, best known for a style of harsh, confrontational noise.