Background

Japanese aesthetics

Zen

Visual arts

Traditional music

Contemporary music

Literature

Films

- Background

- Visual arts

Artists who were inspired by Japanese culture often incorporated its minimalist sensibility, vibrant use of color, and deep connection to nature into their own unique visions.

- Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890)

Van Gogh was heavily inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which he discovered in Paris. The bold colors, flat planes, and unique compositions of these prints influenced his own style, particularly in his use of color and his depiction of everyday scenes.

Courtisane (after Eisen), 1887 Vincent van Gogh

- Claude Monet Monet (1840 – 1926)

One of the leading Impressionists, was influenced by Japanese art, particularly in his famous Water Lilies series. His garden in Giverny was designed with Japanese aesthetics in mind, featuring a Japanese-style bridge and water features that were reminiscent of traditional Japanese gardens.

Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge,1899by Claude Monet

- Pablo Picasso

Picasso was inspired by Japanese prints, particularly during his "Blue Period" and later in his more abstract works. The influence of Japanese art can be seen in his simplified, stylized figures and use of flat planes of color.

- Marc Chagall

Chagall was influenced by Japanese art, particularly in his use of color and dreamlike scenes. His works often feature symbolic and ethereal qualities similar to those in Japanese ink paintings.

- Andy Warhol

Warhol, the king of pop art, was influenced by Japanese culture, particularly in his later works. His fascination with Japanese aesthetics can be seen in his use of repetition, bright colors, and themes of consumerism, which mirror the visual style of many Japanese prints and advertisements.

- Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890)

- Music

Japan has had a profound influence on many musicians and composers across different genres. From classical music to pop, electronic, and experimental soundscapes.

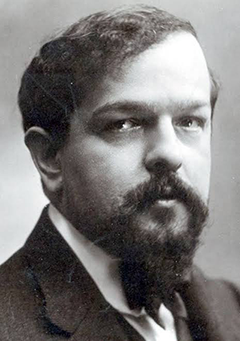

- Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918)

The French composer Claude Debussy was deeply influenced by Japanese music, particularly after attending the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, where Japanese art and culture were prominently featured.

Debussy’s music, especially his Pagodes from Estampes (1903), reflects a fascination with the Japanese aesthetic, with its use of pentatonic scales and shimmering, exotic harmonies that evoke the sound of traditional Japanese instruments like the koto and shamisen.

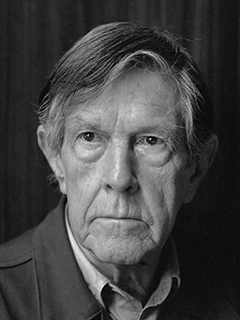

- John Cage (1912 – 1992)

American avant-garde composer John Cage had a strong connection to Japan, both

through his exposure to Zen Buddhism and his interest in traditional Japanese music.

Cage studied Japanese culture and its principles of impermanence and minimalism, which influenced his compositions like 4'33" (1952), a silent piece that reflects Zen’s notion of appreciating the present moment.

- Philip Glass (1937 - )

American minimalist composer Philip Glass was influenced by Japanese music, especially through his studies of Eastern philosophy and music. His operatic works like The Civil Wars and Einstein on the Beach reflect a minimalist approach that echoes the meditative qualities of Japanese art.

Glass was also inspired by the Japanese tradition of repeating motifs, which is central to much of his musical style.

- Dave Brubeck (1920 – 2012)

The legendary American jazz pianist and composer, had a notable connection to Japan, which played a significant role in shaping his career and musical innovations.

"Koto Song" evokes the sound of the traditional Japanese koto, a stringed instrument, and incorporates the delicate, intricate rhythms found in Japanese music. This album, Jazz Impressions of Japan (1964), is perhaps the most direct representation of Brubeck’s fascination with Japan.

- Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918)

- Design

Japan’s influence on design is vast and varied, shaping the work of many creators across different fields. Designers inspired by Japan often focus on themes such as simplicity, elegance, attention to detail, and harmony with nature—all core elements of Japanese aesthetic philosophy.

Whether in fashion, architecture, industrial design, or graphic design, the principles of Japanese culture continue to inspire some of the most innovative and influential designers worldwide.

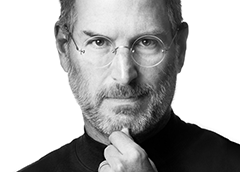

- Steve Jobs (1955 – 2011)

Jobs had a significant connection to Japan, which influenced his philosophy, design thinking, and even his personal life. Japan played an important role in shaping his approach to technology, aesthetics, and business.

Zen's emphasis on simplicity, mindfulness, and focus had a profound impact on his worldview and design philosophy. This is particularly evident in Apple's product designs, which are known for their clean lines, intuitive interfaces, and minimalist aesthetics. Jobs appreciated the Zen principle of "less is more," which is reflected in Apple's design ethos.

- Steve Jobs (1955 – 2011)

- Visual arts

- Japanese aesthetics

- Intro

- The arts in Japan have traditionally reflected the fundamental impermanence—sometimes lamenting but more often celebrating it.

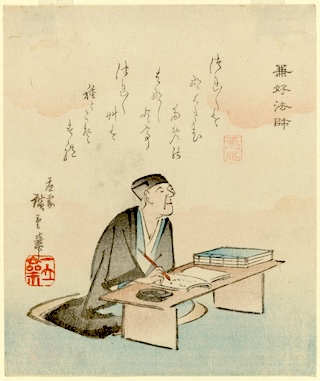

- The idea of impermanence is most forcefully expressed in the writings and sayings of the thirteenth-century Zen master Dōgen, who is arguably Japan’s profoundest philosopher, but there is a fine expression of it by a later Buddhist priest, Yoshida Kenkō 吉田 兼好, whose "Essays in Idleness 徒然草" (1332) sparkles with aesthetic insights.

- Yoshida relates the impermanence of life to the beauty of nature in an insightful manner. He sees the aesthetics of beauty in a different light: the beauty of nature lies in its impermanence.

“Branches about to blossom or gardens strewn with faded flowers are worthier of our admiration. In all things, it is the beginnings and ends that are interesting"

- In the Japanese Buddhist tradition, awareness of the fundamental condition of existence is no cause for nihilistic despair, but rather a call to vital activity in the present moment and to gratitude for another moment’s being granted to us.

- The arts in Japan have traditionally reflected the fundamental impermanence—sometimes lamenting but more often celebrating it.

- Mono no aware 物の哀れ

- It means "the pathos of things" in English. Pathos is the power in literature that creates feelings of sorrow, pity and tenderness.

- When we see things ephemeral like the seasons, flowers, people's lives,... we feel moved with a little sadness.

- The Tale of the Heike 平家物語 (recounts the struggle for power between the Taira and Minamoto houses in the late twelfth century) begins with these famous lines, which clearly show impermanence as the basis for the feeling of mono no aware:

"The sound of the Gion shōja bells echoes the impermanence of all things;

the color of the sōla flowers (Shorea robusta) reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline.

The proud do not endure, they are like a dream on a spring night;

the mighty fall at last, they are as dust before the wind".

- The most frequently cited example of Mono no aware in contemporary Japan is the traditional love of cherry blossoms, as manifested by the huge crowds of people that go out every year to view (and picnic under) the cherry trees.

- The blossoms of the Japanese cherry trees are intrinsically no more beautiful than those of the pear or the apple tree; they are more highly valued because of their transience, since they usually begin to fall within a week of their first appearing.

- It is precisely the evanescence of their beauty that evokes the wistful feeling of mono no aware in the viewer.

- It means "the pathos of things" in English. Pathos is the power in literature that creates feelings of sorrow, pity and tenderness.

- Wabi sabi 侘寂

- According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, wabi may be translated as "subdued, austere beauty," while sabi means "rustic patina."

- Wabi sabi is derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence (三法印, sanbōin), specifically impermanence (無常, mujō), suffering (苦, ku) and emptiness or absence of self-nature (空, kū).

- In traditional Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi is a world view centered on the acceptance of transience and imperfection.

- The aesthetic is described as one of appreciating beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete" in nature.

- The Zencharoku禪茶録 (Zen Tea Record, 1828) by zen monk Jakuan Sōtaku contains a well-known section on the topic of wabi, which begins by saying that it is simply a matter of “upholding the Buddhist precepts”.

"Wabi means that even in straitened circumstances no thought of hardship arises.

Even amid insufficiency, one is moved by no feeling of want.

Even when faced with failure, one does not brood over injustice.

If you find being in straitened circumstances to be confining, if you lament insufficiency as privation, if you complain that things have been ill-disposed—this is not wabi."

- According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, wabi may be translated as "subdued, austere beauty," while sabi means "rustic patina."

- A combined result of the limited natural resources in Japan and the asceticism that characterised the Zen monasteries and lifestyle, simplicity became gradually associated with ultimate refinement and taste.

- When savouring Japanese cuisine, one cannot help noticing that the basic ingredients of the indigenous food are limited to rice, beans, fish, seaweed and root vegetables—the staple diet of the Zen monks. Yet, a remarkable variety of flavours, colors and textures developed out of this limited pallet of ingredients.

- It is a fact that the Japanese culinary inventions are not as lush and flavoursome as those of the neighbouring China or Korea.

- Japanese cuisine has focused on the simplicity and purism of taste instead. By removing all the unnecessary ingredients through a careful filtering process, Japanese cuisine presents a unique example of refined subtlety and transparency in both flavour and presentation.

- Sen no Rikyu 千利休 (1522–1591) is considered the historical figure with the most profound influence on the Japanese "Way of Tea", particularly the tradition of wabi-cha.

- He was attracted by the Korean rough and unrefined pots which eventually replaced the Chinese pots raising the tea ceremony into an art that values the unpretentious, understated and unassuming beauty.

- Having its roots deep in Zen and even further back in the Chinese philosophies of Taoism and Confucianism, "purposelessness" is a fundamental principle of wabi sabi.

- In his book Nampōroku 南方録, (1690), he said

“In the small [tea] room, it is desirable for every utensil to be less than adequate. There are those who dislike a piece when it is even slightly damaged; such an attitude shows a complete lack of comprehension”.

“The meal for a gathering in a small room should be but a single soup and two or three dishes; sakè should also be served in moderation. Elaborate preparation of food for the wabi gathering is inappropriate”

- On the wabi aesthetic, implements with minor imperfections are often valued more highly than ones that are ostensibly perfect; and broken or cracked utensils, as long as they have been well repaired, more highly than the intact.

- Sen no Rikyu saw the rikka style (立花, 'standing flowers', is a form of ikebana. The rikka style reflects the magnificence of nature and its display.) that was popular at the time and disliked its adherence to formal rules. He did away with the formalism and the opulent vases from China, using only the simplest vases for the flower displays in his tea ceremonies.

Ginkaku-ji 銀閣寺, Temple of the Silver Pavilion, officially Jishō-ji 慈照寺

Kinkaku-ji 金閣寺 Temple of the Golden Pavilion, officially Rokuon-ji 鹿苑寺

- In 1987, Kinkaku-ji was covered with gold leaf according to the creator’s original intention. The result is breathtakingly spectacular—but totally un-Japanese.

- Old-time residents of Kyoto famously complained that it would take a long time for the building to acquire sufficient sabi to be worth looking at again.

- At the rate the patina seems to be progressing, probably several centuries.

- Yūgen幽玄 mysterious profundity

- When looking at autumn mountains through mist, the view may be indistinct yet have great depth.

- Although few autumn leaves may be visible through the mist, the view is alluring. The limitless vista created in imagination far surpasses anything one can see more clearly.

- This illustrates a general feature of East-Asian culture, which favors allusiveness over explicitness and completeness.

- Yūgen means the beauty that we can feel sense into an object, even though the beauty doesn’t exist in the literal sense of the word and cannot be seen directly.

- Kamo no Chōmei 鴨 長明 (1153 or 1155–1216), a Japanese poet, considered yūgen to be a primary concern of the poetry of his time. He offers the following as a characterization of yūgen:

“It is like an autumn evening under a colorless expanse of silent sky.

Somehow, as if for some reason that we should be able to recall, tears well uncontrollably.”

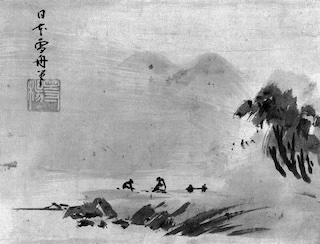

- Yugen is revealed through the artistic practices of Sesshū Tōyō 雪舟 等楊 (1420–1506), a Japanese Zen monk and painter, and his most celebrated work “Splashed ink landscape.” His painting offers insight into a central concept of Japanese aesthetics yūgen.

- Sesshū was part of a trajectory of many centuries to establish Japanese forms of Buddhism as an enduring feature of the country’s religious, philosophic, and aesthetic identity.

Splashed ink landscape 破墨山水図 (1495) by Sesshū

- The mysterious grace of his most celebrated landscape painting derives as much from the space that is left un-touched, the invisible and absent as from what is painted and visible.

- The work appears incomplete, still in the act of formation, and the dramatic negative spaces created by the mists allow the various forms to dissolve and blend into one another, but more decisively, according to the yūgen dynamic, this negativity invites the viewer into the painting to actively complete it.

- Properly estimating the beauty of Sesshū’s Splashed ink landscape—similar to how one should appreciate Japanese calligraphy—involves more than simply making judgments regarding the marks on paper, but also calls for an appreciation of the bodily movements that created the work.

- As artists employing yūgen principles in other genres have shown, the "incompleteness and allusiveness" of the artwork summons the viewer into the scene.

Pine Trees screen 松林図 屏風 (1595) by Hasegawa Tōhaku

- Sesshū did not aim to develop virtuoso skill to create a fully formed art image, but in negating the self and becoming continuous with the motions of nature, they follow the Daoist precept that “the great image has no form.”

Dialogue between Fisherman and Woodcutter 漁樵問答図 by Sesshū

- When looking at autumn mountains through mist, the view may be indistinct yet have great depth.

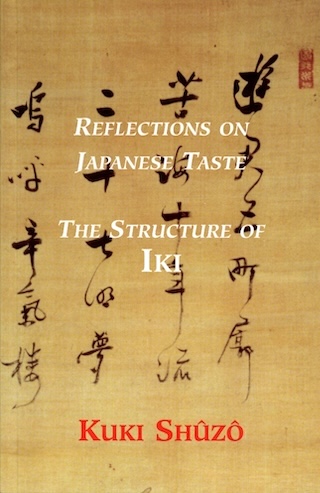

- Iki: Refined Style

- The Structure of Iki (1930) by Kuki Shūzō 九鬼 周造 (1888–1941) is arguably the most significant work in Japanese aesthetics from the twentieth century.

- After positioning the phenomenon of "Iki" among a variety of other aesthetic feelings such as..

sweet (amami) vs astringent (shibumi),

flashy (hade) vs quiet (jimi),

crude (gehin) vs refined (jōhin),

Kuki goes on to examine the objective expressions of the phenomenon, which are either “natural” or “artistic”.

"... parallel lines, and especially vertical stripes, are expressive of iki: almost all the other beautiful patterns developed by Japanese fabric arts, since they often involve curved lines, are un-iki".

"The only colors that embody iki are certain grays, browns, and blues. In architecture, the small Zen teahouse is a paradigm of iki, especially insofar as it initiates an interplay between wood and bamboo".

"Lighting must be subdued: indirect daylight or else the kind of illumination provided by a paper lantern".

- The Structure of Iki (1930) by Kuki Shūzō 九鬼 周造 (1888–1941) is arguably the most significant work in Japanese aesthetics from the twentieth century.

- Kire 切れ : Cutting

- Kire is very important in classical Japanese art forms such as ikebana (arranging flowers), Noh theater (a major form of classical Japanese dance-drama), karesansui (garden-art) and haiku poetry.

- Kire is a fundamental Japanese religio-aesthetic term referring to a Buddhist “cutting off” of everyday life in the sense of “renunciation”.

- The “cut” is a basic trope in the Rinzai School of Zen Buddhism, especially as exemplified in the teachings of the Zen master Hakuin (1686–1769).

- For Hakuin the aim of “seeing into one’s own nature” can only be realized if one has “cut off the root of life”

- Cutting appears in the “cut-syllable” (kireji) in the art of Haiku, which cuts off one image from—at the same time as it links it to—the next.

- In early 1686, Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694) composed one of his best-remembered Haiku:

v.1

Old pond —

frogs jumped in —

sound of water.

v.2

Ah, an ancient pond—

Suddenly a frog jumps in!

The sound of water.

- The most distinctively Japanese style of garden, the "dry landscape garden" 枯山水, owes its existence to the landscape’s being “cut off” from the natural world beyond its borders.

- The epitome of this style is the rock garden at Ryōanji in Kyoto, where fifteen mountain-shaped rocks are set in beds of moss in a rectangular “sea” of white gravel.

- At Ryōanji, the rock garden is cut off from the outside by a splendid wall that is nevertheless low enough to permit a view of the natural surroundings.

- Above and beyond the wall there is nature in movement: branches wave and sway, clouds float by, and the occasional bird flies past.

- But unless rain or snow is falling, or a stray leaf is blown across, the only movement visible within the garden is shadowed or illusory, as the sun or moon casts slow-moving shadows of tree branches on the motionless gravel.

- There is a striking contrast between the severe rectangularity of the garden’s borders and the irregular natural forms of the rocks within them.

- Each group of rocks is "cut off" from the others by the expanse of gravel, and the separation is enhanced by the “ripple” patterns in the raking that surrounds each group (and some individual rocks).

- The cut appears as a fundamental feature in the distinctively Japanese art of flower arrangement called "ikebana 生け花".

- The term means literally “making flowers live”—a strange name for an art that begins by initiating their death.

- Nishitani Keiji 西谷 啓治 (1900-1990), a Japanese philosopher. In his essay, The Japanese Art of Arranged Flowers:

"... organic life is "cut off" precisely in order to let the true nature of the flower to come to the fore".

"... the beauty expressed in ikebana is created to last only for a short time. Such art changes with the season and reveals its beauty only for the few days after the flowers and branches have been cut"."The essential beauty lies in its being transitory and timely. It is a beauty which embraces time, a beauty which appears out of the impermanency of time itself".

"From the perspective of their fundamental nature, all things in the world are rootless blades of grass. Such grass, however, having put roots down into the ground, itself hides its fundamental rootlessness"."Through having been cut from their roots, they are, for the first time, made to thoroughly manifest their fundamental nature—their rootlessness".

- Kire-tsuzuki 切れ続き literally means “cut and continue,” which makes the philosophical aspect of kire more explicit.

- The notion of cut-continuation is exemplified in the highly stylized gait of the actors in the Nō drama.

- The actor slides the foot along the floor with the toes raised, and then “cuts” off the movement by quickly lowering the toes to the floor—and beginning at that precise moment the sliding movement along the floor with the other foot.

- This stylization of the natural human walk draws attention to the episodic nature of life, which is also reflected in the pause between every exhalation of air from the lungs and the next inhalation.

- Kire is very important in classical Japanese art forms such as ikebana (arranging flowers), Noh theater (a major form of classical Japanese dance-drama), karesansui (garden-art) and haiku poetry.

- Zen 禅

- Zen philosophy (one of the primary branch of Buddhism)

- Many forms of Japanese art have been influenced by Zen philosophy over the past thousand years, with the concepts of the acceptance and contemplation of imperfection, and constant flux and impermanence of all things being particularly important to Japanese arts and culture.

- As a result, many of these art forms contain and exemplify the ideals of wabi sabi.

- Many forms of Japanese art have been influenced by Zen philosophy over the past thousand years, with the concepts of the acceptance and contemplation of imperfection, and constant flux and impermanence of all things being particularly important to Japanese arts and culture.

- Zen philosophy (one of the primary branch of Buddhism)

- Suzuki Daisetsu 鈴木大拙 (1870 - 1966) a Japanese philosopher, religious scholar

- He was the great Japanese scholar who introduced Zen to the West, settled in New York in 1950.

- Jonh Cage sought out Suzuki’s Columbia University class and found release from the self-judgment and fear that shattered him in the 1940s.

- Suzuki showed him a completely different way of regarding the world and became one of his most decisive teachers.

"Before studying Zen,

men are men and mountains are mountains.

While studying Zen,

things become confused.

After studying Zen,

men are men and mountains are mountains."

After telling this, Dr. Suzuki was asked,

“What is the difference between before and after?” He said,

“No difference,

only the feet are a little bit off the ground.”

- Dōgen Zenji (道元禅師 1200 – 1253) a Japanese Zen Buddhist monk, writer, poet, philosopher

“Before one studies Zen, mountains are mountains and waters are waters;

after a first glimpse into the truth of Zen, mountains are no longer mountains and waters are no longer waters;

after enlightenment, mountains are once again mountains and waters once again waters.”

- Zen showed Cage his true nature: peaceful, loving, joyful. His response was immediate: He would put all these soaring insights into his music.

- In Japan, a trip organized by Toshi Ichiyanagi and Yoko Ono in 1962, Cage immediately set off to D. T. Suzuki’s house.

- Ten years after the debut of 4’33”, Cage honored his 92 year old teacher and the teachings that had shown him the heart of "silence".

- He was the great Japanese scholar who introduced Zen to the West, settled in New York in 1950.

- John Cage's Connections to Buddhism

- John Cage found great inspiration in Zen Buddhism for his life and work.

- Cage composed various pieces of music in a spiritual rather than a rational sense, moments of illumination, unexpectedness, and even absurdity.

- John Cage found great inspiration in Zen Buddhism for his life and work.

- In 1983 Cage created a series of drawings entitled Where R=Ryoanji. He placed fifteen smooth stones on a paper and drew around them their outlines.

- Cage also composed Ryoanji (for oboe and voice) between 1983 and 1985.

“Each two pages are a garden of sounds. The glissandi are to be played smoothly and as much as is possible like sound events in nature rather than sounds in music.”

- The principle behind the composition of Ryoanji was simple: by placing the rock outlines on graphic paper, Cage converted them into pitch-specific melodic outlines.

- The stone density (their relative placement on the paper surface), the type of pencil, the amount of pressure, the number of tracings and so on, were controlled by "chance operations" determined with the use of I-Ching.

- The concept of “chance operations” refers to the strategy of incorporating randomness or unpredictability into works of art, music, literature, or any situation.

- Although this method of composition seems quite at odds with the intuitive character of wabi sabi, at the same time it ensures an almost absolute transference of the architectural design into music, a type of musical blueprint of the actual garden, hence sharing the same aesthetic language as the original model.

- The careful selection of the musical ingredients and their closely-knit correspondence to their raw physical model is a reference to the natural organic beauty of the wabi sabi where not a single detail is superfluous to the design.

- Musical parameters, such as duration, pitch, dynamics etc are determined by the physical characteristic of the stones or the use of chance operations thus creating a musical reality that conveys faithfully and in its totality the artlessness and purposelessness inherent in wabi sabi.

- Visual arts

- Ukiyo-e 浮世絵

- Ukiyo-e are Japanese woodblock prints, which flourished during the Edo Period (1603-1868).

- Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾 北斎 (1760–1849) a Japanese ukiyo-e artist of the Edo period. His Ukiyo-e significantly influenced Impressionists such as Monet, Manet, Renoir, and Van Gogh.

- These Impressionist painters created many works of art based on Ukiyo-e, incorporating its visual style and compositional techniques.

Almond Blossom (1890) Van Gogh

Water-Lilies and Japanese-Bridge (1899) Claude Monet

- Hokusai’s famous Ukiyo-e of a wave had originally inspired Claude Debussy (1862-1918) to compose La Mer.

The Great Wave, Katsushika Hokusai

What links ‘The Great Wave’ and Debussy’s ‘La Mer’?

- Ukiyo-e are Japanese woodblock prints, which flourished during the Edo Period (1603-1868).

- Ukiyo-e 浮世絵

- Lee Ufan (1936- ) a Korean minimalist painter, sculptor based in Japan

- Lee Ufan came to prominence in the late 1960s as one of the major theoretical and practical proponents of the avant-garde Mono-haもの派 (Object School) group.

- Lee Ufan came to prominence in the late 1960s as one of the major theoretical and practical proponents of the avant-garde Mono-haもの派 (Object School) group.

- The Mono-ha school of thought was Japan’s first contemporary art movement to gain international recognition.

- It rejected Western notions of representation, focusing on the relationships of materials and perceptions rather than on expression or intervention.

- Akio Suzuki (1941- ) a Japanese musician, sound artist, inventor, instrument builder

- John Maeda (1966 - ) a Vice President of Design and Artificial Intelligence at Microsoft

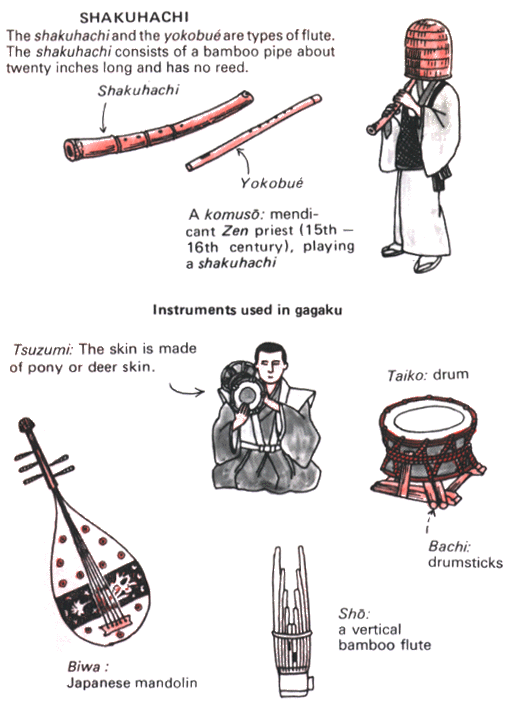

- Traditional music

- Noh能: Chu no mai中之舞

- As music more than any other art is the most direct expression of the aesthetic framework of a given culture, it is inevitable that traditional Japanese music would feature a similar if not greater relationship with the aesthetic of wabi sabi.

- "Noh" is a major form of classical Japanese dance-drama that has been performed since the 14th century.

- "Chu no mai" is one of the Noh dances. It is performed at a level between a quiet dance and a fast dance, and is considered the basis of the dances.

- Its orchestration is minimal and transparent consisting of just one flute (nokan) and three percussion instruments (ko-tsuzumi, o- tsuzumi and taiko) in total.

- Although Noh music has been crystallized in an aesthetic and technical framework that stands very much on its own, one cannot help noticing in it the deeply rooted presence of fundamental aesthetic principles of wabi sabi.

- As music more than any other art is the most direct expression of the aesthetic framework of a given culture, it is inevitable that traditional Japanese music would feature a similar if not greater relationship with the aesthetic of wabi sabi.

- Gagaku雅楽, elegant music

- Described by musicologists as one “of the oldest orchestral musics in the world”.

- Gagaku originates from the court music of China which was imported and established in Japan in the first half of the ninth century.

- The many techniques possible on various gagaku instruments are generally not all exploited. Rather, there is a concentration on only a few basic sounds in order to enhance their effectiveness.

- Therefore unlike the chamber music that made its appearance later in the West, gagaku seems bare, almost simplistic.

- Gagaku makes use of a common Japanese principle of elastic or breath rhythm. The melody moves from beat to beat in a rhythm more akin to that of a breath taken deeply, held for an instant, and then expelled.

- Described by musicologists as one “of the oldest orchestral musics in the world”.

- Contemporary music

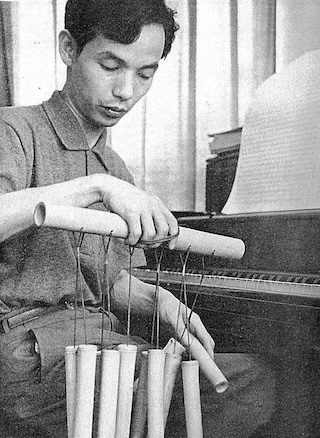

- Takehisa Kosugi (1938–2018) a Japanese composer, musician – a pioneer of experimental music

- Kosugi co-founded "Group Ongaku" in 1960 with Mieko Shiomi and Yasunao Tone, which was “famously the first ensemble in Japan to explore collective group improvisation and multi-media happenings”.

- The incidental or indeterminate nature of sounds has been one of the major characteristics of his music through improvisational performances and sound installations.

- Kosugi co-founded "Group Ongaku" in 1960 with Mieko Shiomi and Yasunao Tone, which was “famously the first ensemble in Japan to explore collective group improvisation and multi-media happenings”.

- Tone Yasunao 刀根 康尚 (1935- )

- A multi-disciplinary artist born in Tokyo, Japan and working in New York City.

- A multi-disciplinary artist born in Tokyo, Japan and working in New York City.

- Mieko Shiomi (1938–) a Japanese artist, composer, and performer

- Mieko Shiomi co-founded the Group ‘Ongaku’ with Takehisa Kosugi and Yasunao Tone.

“We experimented with the various components of every instrument we could think of, like using the inner frame of the piano, or using vocal and breathing sounds, creating sounds from the wooden parts of instruments, and every conceivable device of bowing and pizzicato on stringed instruments.

We even turned our hands to making music with ordinary objects like tables and chairs, ash trays and a bunch of keys.”

- Shiomi is best known for her event pieces and objects, such as Disappearing Music for Face, Endless Box, and Spatial Poem series.

- Mieko Shiomi co-founded the Group ‘Ongaku’ with Takehisa Kosugi and Yasunao Tone.

- Toru Takemitsu 武満 徹 (1930-1996)

- Largely self-taught, Takemitsu was admired for the subtle manipulation of instrumental and orchestral timbre.

- He is known for combining elements of oriental and Western philosophy and for fusing sound with silence and tradition with innovation.

- During the post-war years, he came into contact with Western music through radio broadcasts by the American occupying forces – not only jazz, but especially classical music by Debussy and Copland and even by Schoenberg.

- In 1951, Takemitsu co-founded “Experimental Workshop” which was an interdisciplinary group of artists, musicians, choreographers and poets who were inspired by European and American avant-gardes.

- He composed November Steps for biwa, shakuhachi and orchestra (1967) in the form of the deliberate juxtaposition of Eastern and Western musical culture.

- The Western musical tradition and the Eastern aesthetics of wabi sabi are placed side by side. Their co-existence is not a matter of competition but of mutual respect and consideration.

- Takemitsu uses his instinctive awareness of the Japanese tradition as a tool for an interpretive refinement.

- By means of a simple, uncluttered score, in a similar manner as in Ryoanji’s deliberate minimalism, he encourages the performers to take interpretational liberties and use their mastery to ‘compose’ the missing elements.

- Though there is no concrete evidence that cadenza is a specific reference to the wabi sabi concept of incompleteness, it is undeniable that the Japanese instrumental medium has had a profound effect on the shape and style of the work.

- Largely self-taught, Takemitsu was admired for the subtle manipulation of instrumental and orchestral timbre.

- Takemitsu once addressed that John Cage profoundly influenced his music.

- Japanese inspired music

- Undoubtedly there is an increasing number of Western composers who have used elements of Japanese culture as the main subject, or inspiration for their compositions.

- Jazz Impressions Of Japan by Dave Brubeck Quartet “Koto Song” was inspired by two female musicians in Kyoto.

- In the notes to the original album, Jazz Impressions of Japan, Brubeck describes the instrument and delicate music it produced:

“Of the classical instruments I heard, I was most fascinated by the koto....

The koto is an instrument of rare delicacy and beauty, which blended with voice or flute, seems to suggest the ethereal quality of Japan’s gardens and misty landscapes.

- Undoubtedly there is an increasing number of Western composers who have used elements of Japanese culture as the main subject, or inspiration for their compositions.

"John Cage shook the foundations of Western music and he evoked silence as the mother of sound. Through John Cage, sound gained its freedom. His revolution consisted of overthrowing the hierarchy in art."

- Literature

- Haiku 俳句

- A traditional Japanese haiku is a three-line poem with seventeen syllables, written in a 5/7/5 syllable count.

- Often focusing on images from nature, haiku emphasizes simplicity, intensity, and directness of expression.

- By withholding verbose and long-winded descriptions the poem entices the reader to actively participate in the fulfillment of its meaning and, as with the Zen gardens, to become an active participant in the creative process.

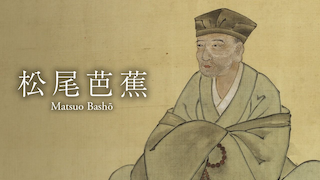

- Matsuo Bashō 松尾 芭蕉 (1644–1694), the most famous Japanese poet of the Edo period, was credited with establishing "sabi" as definitive emotive force in haiku.

- Many of his works, as with other wabi-sabi expressions, make no use of sentimentality or superfluous adjectives, only the "devastating imagery of solitude."

- Solitary now —

Standing amidst the blossoms

is a cypress tree.

Old pond —

frogs jumped in —

sound of water.

Ah, tranquility!

Penetrating the very rock,

A cicada’s voice.

- A traditional Japanese haiku is a three-line poem with seventeen syllables, written in a 5/7/5 syllable count.

- Junichiro Tanizaki 谷崎潤一郎 (1886–1965) was a Japanese author who is considered to be one of the most prominent figures in modern Japanese literature.

- Tanizaki’s essay In Praise of Shadows 陰翳礼讃 (1933) frequently celebrates "sabi". By contrast with Western taste, he writes of the Japanese sensibility.

"We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates… Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty."

"We do not dislike everything that shines, but we do prefer a pensive lustre to a shallow brilliance, a murky light that, whether in a stone or an artifact, bespeaks a sheen of antiquity. . . "

"We love things that bear the marks of grime, soot, and weather, and we love the colors and the sheen that call to mind the past that made them."

"... when we gaze into the darkness that gathers behind the crossbeam, around the flower vase, beneath the shelves, though we know perfectly well it is mere shadow, we are overcome with the feeling that in this small corner of the atmosphere there reigns complete and utter silence; that here in the darkness immutable tranquility holds sway."

"A simple structure, but a special and evocative one, a place of deeply philosophical depths. A space cut out of the room, which cuts off direct light and thereby opens up a new world: these techniques developed distinctively in the Japanese tradition of architecture."

- Tanizaki’s essay In Praise of Shadows 陰翳礼讃 (1933) frequently celebrates "sabi". By contrast with Western taste, he writes of the Japanese sensibility.

- Haiku 俳句

- Snow Country 雪国, a novel by the Japanese author Yasunari Kawabata.

- The novel is considered a classic work of Japanese literature and was among the three novels the Nobel Committee cited in 1968, when Kawabata was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

- “The train came out of the long border tunnel into the snow country.”-「国境の長いトンネルを抜けると雪国であった」

- Portraying the wabi sabi in Snow Country: Snow country depicts beauty of nature, people, and love through the characters and the situation with the elements of sincerity, purity, and calmness.

- Beauty itself is one of the major themes in this novel. However, Kawabata has his own perception of the beauty that is different with common perception of beauty. These beauty were analyzed through philosophical point of beauty by Kant.

- In fact, the writer found that almost all of beauty in snow country included the 'sad' element, such as a 'loneliness' in a beauty of nature, 'sadness' in a beautiful voice and a waste effort in a beauty of love.

- The novel is considered a classic work of Japanese literature and was among the three novels the Nobel Committee cited in 1968, when Kawabata was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

- Films

- Ozu Yasujirō (1903-1963) a Japanese filmmaker

- The films of Ozu— often thought to be the most “Japanese” of Japanese film directors — are a series of exercises in conveying "mono no aware".

- In his book, I only make tofu because I am a tofu maker 僕はトウフ屋だからトウフしか作らない:

“It is possible to eat many different types from around the world at a restaurant in a Japanese department store, but as a result of this overly abundant selection the quality of the food and its taste suffers.

Filmmaking is the same way. Even if my films appear to all be the same, I am always trying to express something new, and I have a new interest in each film. I am like a painter who keeps painting the same rose over and over again.”

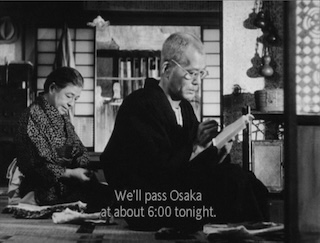

- Late Spring 晩春 (1949): A vase standing in the corner of a tatami-matted room in front of a window on which silhouettes of bamboo are projected; two fathers contemplating the rocks in a “dry landscape” garden; a mirror reflecting the absence of the daughter who has just left home after getting married—all images that express the "mono no aware (pathos of things)" as powerfully as the expression on the greatest actor’s face.

- His characters tend to face the same way, sitting or standing side by side. This reflects the Japanese avoidance of eye contact, but also suggests that they are trying to find a mutual course of action, instead of confronting one another.

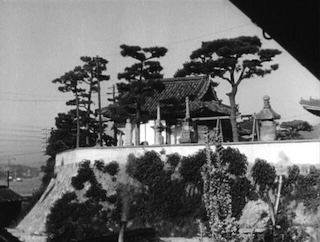

- Ozu's most endearing characteristic is what's called his "pillow shots." The term comes from the "pillow words" used in Japanese poetry — words that may not advance or even refer to the subject, but are used for their own sake and beauty, as a sort of punctuation.

“Film returns to us and extends our first fascination with objects, with their inner and fixed lives” applies consummately to Ozu, who often expresses feelings through presenting the faces of things rather than of actors. — Stanley Cavell

- In Ozu, a sequence will end and then, before the next begins, there will be a shot of a tree, or a cloud, or a smokestack, or a passing train, or a teapot, or a street corner. It is simply a way of looking away, and regaining composure before looking back again.

- The films of Ozu— often thought to be the most “Japanese” of Japanese film directors — are a series of exercises in conveying "mono no aware".

- Ozu Yasujirō (1903-1963) a Japanese filmmaker

- Tokyo Story 東京物語 (1953): The opening shots of Tokyo Story are also exemplary with respect to the cutting.

- Floating Weeds / Ukikusa (1959)

- For each cut Ozu has arranged for at least one formal element to provide continuity (kire-tsuzuki) between the adjacent scenes.

- Ozu’s inconspicuous switches remain among the most stylish cuts in world cinema, and his work continues to be a source of inspiration.

- An unusual aspect of Ozu’s grave is that the granite headstone is marked only by a single kanji character: 無 (mu), which stands for “nothing” or “nothingness.”

- Aki Kaurismäki is a Finnish film director and screenwriter

Aki Kaurismaki on Ozu -

Leningrad Cowboys Go America (1989) by Aki Kaurismaki

- Miyazaki Hayao (1941- )

- Miyazaki is an influential Japanese anime director whose lyrical and allusive works have won both critical and popular acclaim.

- His notable films include Princess Mononoke (1997), Spirited Away (2001), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), and The Boy and the Heron (2023).

- Miyazaki is an influential Japanese anime director whose lyrical and allusive works have won both critical and popular acclaim.

- Touch The Sound (2004)

A documentary which explores the connections among sound, rhythm, time, and the body by following percussionist Evelyn Glennie, who is nearly deaf.