Abstract art

Abstract animation

Musical influences

Spiritual fulfillment

Watching abstract animation

- Abstract art

- Definition

- Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect.

- Abstraction was one of the most revolutionary and important innovations of avant-garde artists working in the visual arts in the early 20th Century.

- Visual abstraction also emerged within the early pioneering works of cinema and experimental animation.

- Partly this was due to artists desiring to create "art in motion" by using the medium of film.

- Abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect.

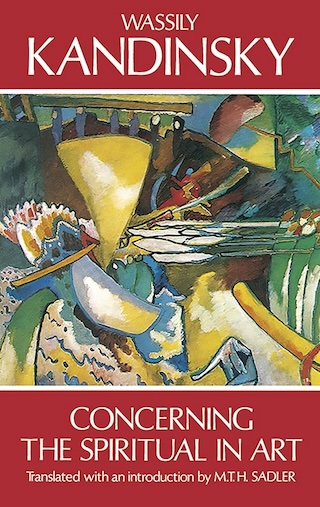

- Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) a Russian painter and art theorist.

- Kandinsky is generally credited as one of the pioneers of "abstraction" in Western art.

- Kandinsky’s life would be driven by the pursuit of creativity that no longer concentrated on pictorial representation of the objective world but instead sought to symbolize “inner need” of the artist, seeking spiritual awakening and transcendence through the medium of art.

- Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911) Kandinsky defines three types of painting: impressions, improvisations and compositions. While impressions are based on an external reality that serves as a starting point, improvisations and compositions depict images emergent from the unconscious, though composition is developed from a more formal point of view.

"Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.

“The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural … The brighter it becomes, the more it loses its sound, until it turns into silent stillness and becomes white.”

“A painter, who finds no satisfaction in mere representation, however artistic, in his longing to express his inner life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end. He naturally seeks to apply the methods of music to his own art.”

- Kandinsky is generally credited as one of the pioneers of "abstraction" in Western art.

- Kandinsky had a great interest in music. He was always fascinated by the 'synesthesia' - when you listen to music, but you see shapes or colors, or hear words - relationship between music and painting.

- When Kandinsky first heard Wagner’s opera Lohengrin (premiered 1850) as a young man, he was moved by the powerful imagery the music evoked in his mind. Kandinsky later recollected in his 1911 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

“I saw all my colors in my mind; they stood before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.

- The visual symphony Kandinsky experienced may have been the result of a rare neurological phenomenon known as 'synesthesia'.

- Kandinsky longed to imbue his canvases with the abstract melodic language of the universal sensations of the inner soul.

- While impressions were predominantly inspired by external reality, improvisations and more developed compositions were birthed by unconscious and spontaneous expressions stimulated by inner feelings and subjective experience.

"Kandinsky is painting music. That is to say, he has broken down the barrier between music and painting..." - Michael T. H. Sadler Harvey, an English novelist

- Definition

- Abstract animation

- Characteristics of abstract animation

- It is a subgenre of experimental film and animation, and a form of abstract art.

- There is no characters with which to identify.

- There is no clear story the viewers to follow.

- It is often 'about' the need to expand our ability to see, experience, and comprehend things in everyday life.

- It challenges the viewer to participate in the process of creating meaning and to develop feelings about the work.

- The viewer does not have a complete understanding of its meaning as he would with a narrative structure.

- It does not offer the viewer certain pleasure usually found in watching a structured film.

- It does not mean that abstract animation does not offer any pleasure. It does, but as an 'open text', which leads beyond the film itself, as opposed to a 'closed text' which provides tangible information within the film and, at the end, a clear resolution of the film's plot.

- In 1926, the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp (a French painter, sculptor, whose work is associated with Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art) released Anémic Cinéma, filmed in collaboration with Man Ray.

- He made this piece by filming nine rotating cardboard disks with spirals drawn on them and ten rotating disks inscribed with verbal puns.

- From its beginnings to the contemporary, abstract animation involves 'experimentation' at its essence, while the rich heritage of abstract animation becomes transformed through digital technology.

- Abstraction remains an important style or vehicle of artistic expression in the medium of animation.

- Abstract form is not merely a visual style; it may be regarded as a mode of thinking and creative visualization that is highly relevant to post-modern times in our perception and understanding of the world around us.

- It is a subgenre of experimental film and animation, and a form of abstract art.

- Characteristics of abstract animation

- Musical influences

- Using musical elements

- Music was an extremely influential aspect of abstact film and animation. Abstract film artists are known to use musical elements such as rhythm, tempo, dynamics, and fluidity.

- Norman McLaren says "Music is organized in terms of small phrases, bigger phrases, sentences, whole movements and so on. To my mind, animation is the same kind of thing".

- Many abstract animators have been greatly inspired by music which has provided models in terms of content as well as form.

- Jordan Belson (1926–2011) was an American artist and abstract cinematic filmmaker who created nonobjective, often spiritually oriented, abstract films.

Allures (1961) Jordan Belson

- He went beyond visual experimentation for art's sake, finding that music provided guidelines for an equally engaging spiritual quest.

Music of the Spheres (1977)

- Jules Engel (1909–2003) was an American filmmaker of Hungarian origin. He was the founding director of the experimental animation program at the California Institute of the Arts. Abstract painter and animator also sees his animated works as being compatible with music.

The Kinetica Video Library™ Presents: Jules Engel Selected Works, Volume I

"... conductors, composers and musicians have all spokn to me about my work. They describe the composition, timing and direction they sense from my films as musical.

They are moved by the rhythm and by the "complete, fulfilling process."

- But Engel's definition of sound ranges far beyond music. He writes...

"...Sound is natural. When visiting a museum, there is not a musical score playing in the background as we gaze at the painting. But sound is always present; someone's footsteps, a throat being cleared, or whispers of viewers sharing thoughts.

So as it is in my films, 'sound score' is often far more appropriate, since a formal music composition is not always necessary to provide enhancement, nor is always the basis of stimulus."

- Music was an extremely influential aspect of abstact film and animation. Abstract film artists are known to use musical elements such as rhythm, tempo, dynamics, and fluidity.

- Using musical elements

- Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) an Austrian-American composer who created new methods of musical composition involving atonality, namely serialism and the 12-tone row.

- "Atonal music" is a style of music that does not adhere to the traditional harmonic concept of a key or mode.

- Kandinsky praised Arnold Schoenberg,

"Schoenberg's music leads us into a realm where musical experience is a matter not of the ear but of the soul alone... Schoenberg, whose influence as a composer has been immeasuable..."

- Like Kandinsky, Schoenberg was motivated to a great extent in his artwork by spiritual and philosophical inquiry.

- Schoenberg's works and theories made a significant impact upon abstract animation, particularly in the wok of James and John Whitney.

John Whitney (1917–1995) an American animator, composer, widely considered to be one of the pioneers of computer animation.

James Whitney (1921–1982), younger brother of John, was a filmmaker regarded as one of the great masters of abstract cinema. Several of his films are classics in the genre of visual music.

- John Whitney whose theoretical considerations have centered around the analogies between film structure and music, counted Schoenberg among his most important influences.

- For John Whitney, the composer's theories of twelve-tone music provided a rational structural model by which to pursue his primary goal, 'the idea of achieving a fluid visualization of music'.

- "Atonal music" is a style of music that does not adhere to the traditional harmonic concept of a key or mode.

- While the spiritual elements of Schoenberg's work have been noted by Kandinsky and many others, Whitney felt they were not significant to his own investigations, explaining:

- Color (light) organ

- The term color organ refers to a tradition of mechanical devices built to represent sound and accompany music in a visual medium.

- The earliest created color organs were manual instruments based on the harpsichord design.

- In the early 20th century, a silent color organ "Lumia" developed by Thomas Wilfred (1889–1968).

- The dream of creating a visual music comparable to auditory music found its fulfillment in "animated abstract films" by artists such as Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye and Norman McLaren; but long before them, many people built instruments, usually called "color organs", that would display modulated colored light in some kind of fluid fashion comparable to music.

Luccata, Op. 162 (1967-68) Thomas Wilfred

- In the 1960s and 1970s, the term "color organ" became popularly associated with electronic devices that responded to their music inputs with "light shows."

Liquid Loops (1969) The Joshua Light Show

- The term color organ refers to a tradition of mechanical devices built to represent sound and accompany music in a visual medium.

"If you look at the spead of western music, there are composers like Bach who achieved very profound emotional associations with religious experience but also much of their work is elegantly formal and very simple.

It doesn't need to have any amplification, or any relations other than what it is. I felt no need to go beyond that. I was looking for formal patterns and dynamics, fluidity."

- Spiritual fulfillment

- Pythagorean influences

- While it is true that many abstract animations were made as formal investigations, a significant number of them were created as part of a quest for expanded consciousness and spiritual fulfillment.

- The relationship between music and spirituality was explored by Pythagoras, a philosopher who lived during the fifth century BC. The theorist's thinking affected the work of such abstract animators as Oskar Fischinger and Jordan Belson.

- Although he was evidently not drawn to the spiritual elements of Pythagoras's theories, John Whitney was nontheless immensely influenced by the philosopher's conception of harmony.

- He notes that Pythagorean influences and a casual connection between Islamic ideas of cosmos, music, geometry and achitecture significantly influenced the creation of his film, Arabesque (1975).

Arabesque (1975) John Whitney

- While it is true that many abstract animations were made as formal investigations, a significant number of them were created as part of a quest for expanded consciousness and spiritual fulfillment.

- To varying degrees, artsits such as Norman McLaren, Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye, Harry Smith, Jordan Belson and James Whitney saw abstract art as a means of unsderstanding themselves and the world around them.

- Their work in abstract animation paralleled other activities in their lives, such as meditation.

- Mandalas

- A mandala ('round' or 'circle') is a symmetrical image, that is an important component of Hindu and Buddhist religious practices.

- In that context, mandalas have symbolic meaning - generally representing the cosmos, deities, knowledge, magic and other powerful forces - and often are used to assist concentration and meditations.

- One of the primary goals of meditational practice is to achieve a deeper understanding of oneself and the meaning of life.

- Oskar Fischinger (1900-1967) was a German-American abstract animator, filmmaker, and painter, notable for creating abstract musical animation many decades before the appearance of computer graphics and music videos.

- William Moritz (1941–2004), a film historian, specialized in visual music and experimental animation, has noted the influence of meditational imagery on the work of Oskar Fischinger, who studied Tibetan Buddhism.

- He explains that film, Radio Dynamics (1942), was 'designed specifically as a meditative vehicle' and many of his works are highly spiritual in nature.

Radio Dynamics (1942) Oskar Fischinger

- According to Moritz, these artists' abstract animations are often meant to be looked at with a centered gaze, where you are actually looking at the center of the screen.

- They are designed for that concentration, which is different from a lot of ordinary cinema, where the eye is meant to wander around and pick out details and have its own discourse with the film.

- In Lapis (1966), James Whitney employs several visual strategies to encourage the viewer to fix his or her vision on, or become enteranced by his images.

- For example, near the beginning of the film, shortly after the title appears, images grow smaller and seem to recede into the frame, pulling the spectator's vision in with them.

- This design technique is used at other points in the film, along with a widening of a black circle within a circle, which also tends to pull in the viewer's focus (the viewer feels as if he is being drawn into the figure).

- The use of ligtht and color fields also affects the viewing experience, as images in Lapis tranform fluidly from dark to light, or strobe effects send out a shocking pulse of white light.

- You can become entranced by the light in combination with the rhythmic, hypnotic imagery projected on the screen. The moving mandala works in time, more like music, to induce a trance-like state.

- Although they are not mandala films, one can see a similar aesthetic operating in McLaren's Lines films - Lines Vertical (1960) and Lines Horizontal (1962) - and Mosaic (1965), which are made from the same images combined in different ways.

- Similar to Lapis, the progression of action in the Lines films follows the structure of much Hindu classical music, with its very slow, thin opening, its very gradual uninterrupted build-up in complexity, rhythm and richness to a final stunning climax.

- Watching abstract animation

- Left brain vs Right brain

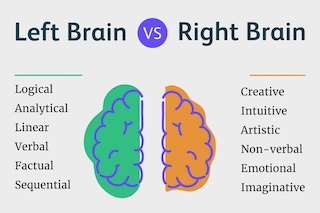

- Some theorists have speculated that one's ability to create and appreciate cinematic images is tied into the functioning of different areas of the brain.

- The classical model of film, with its linear narrative structure of uni-directional cause-and-effect relationships - one or more things happen as a result of something - is one that seems to draw largely on abilities controlled by the 'left hemisphere' of the brain.

- In contrast, abstract work demands much more of the 'right hemisphere', since it requires the viewer to think intuitively.

- It has been theorized that the two parts work in tandem throughout the day and night, although the left side of the brain dominates during waking hours while the rigtht side is most active during periods of sleep and dreaming.

- People have an aversion to thinking with the 'right hemisphere' (strictly intuitive), willing to forego reason and logic, because they do not like the loss of 'control' that comes with intuitive thinking (right hemisphere).

- If asked to interpret an experience that is highly reliant on right-hemispheric capabilities, the inexperienced viewer might feel anxiety because her normal 'left-hemisphere' cognitive faculties are left untethered.

- However, once an individual realigns her expectations and learn to be comfortable with the less-structured experience, the process of viewing abstract work becomes increasingly pleasurable.

- Some theorists have speculated that one's ability to create and appreciate cinematic images is tied into the functioning of different areas of the brain.