http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/biogeog/BERR1937.htm

Tertiary Floras of Eastern North America1

by Edward W. Berry (1937)

Editor Charles H. Smith's Note: Original pagination

indicated within double brackets. Notes are numbered sequentially and

grouped at the end, with the page(s) they originally appeared at the bottom

of given within double brackets. Reprinted with permission from

the New York Botanical Garden Press. Originally published in The Botanical

Review, Vol. 3, pp. 31-46, copyright 1937, The New York Botanical

Garden.

[[p. 31]] INTRODUCTION

The greatest impediment to a botanical or zoological approach to geological history is the general lack of realization of the enormous lapse of time involved and, consequently, a complete lack of perspective or orientation. A treatise could be written on this subject but it will suffice to recall, by way of illustration, how John Lindley--an acute enough botanist and an outstanding figure in the history of botanical thought--was constrained because of this lack, and inspired by his hostility to evolutionary ideas, to see cacti, arborescent spurges and other systematically advanced types in the sigillarias and their associates of the Carboniferous period.

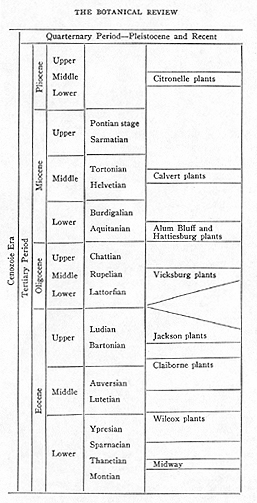

It is important, therefore, in any discussion of Tertiary floras, to furnish some sort of time-table as a frame of reference. The science of geology has not yet reached the position in which it is possible to correlate events very precisely from continent to continent, but the chronological terminology should, as far as possible, be international rather than provincial, and the majority of scientific nations are moving in this direction, if only to be understood, and despite the deplorable resurgence of nationalism in their points of view on all other questions.

The following abbreviated scheme will be sufficient for the present purpose. At the left are the familiar and understandable major divisions of the Tertiary. In the fifth column are the stages of the international time scale which make up the Tertiary, and at the right are the principal plant horizons thus far known in eastern North America. This serves to indicate how incomplete the paleobotanical record of the 54 to 63 millions of years of the whole Tertiary2 really is in eastern North America.

With but a single exception, the known Tertiary floras of eastern North America are confined to the present day physiographic province known as the Coastal Plain, the Atlantic and

[[p. 32]]

[[p. 33]] Gulf Coastal Plain, or as the Atlantic Coastal Plain--the last usage being preferable.

The Atlantic Coastal Plain, now submerged northeast of Long Island and partially emerged from New York to Mexico, is unique among similar features of the earth in its extent, in its lack of any considerable deformation, and in the relative continuity of its picture of geological history from the Lower Cretaceous to the present--a lapse of time variously estimated as being between 120 and 149 millions of years.3 Its paleobotanical history is fairly continuous from about the middle of the Lower Cretaceous through the Upper Cretaceous and the Eocene. In other words, it gives a rather more complete picture of that part of the floral history of the world than does any other region during a time when the flowering plants (angiosperms) assumed the dominant rôle on land which they display at the present time.

The Coastal Plain lies to the south and east of the Appalachian region, which last has been a land area since before the close of the Paleozoic era. This old land, although probably not the original home, was at least one of the theaters of evolution of the flowering plants. From western Greenland to Texas there have been found abundant records of land plants from the Lower Cretaceous into the Tertiary, and in this region the flowering plants make their appearance toward the close of the Lower Cretaceous (Potomac group of formations) associated with many descendents of Jurassic ferns, cycads, and conifers. These flowering plants increase greatly in number and variety during the Upper Cretaceous, which time marks the first modernization of the floras of the world, but they are accompanied until the close of the Cretaceous by the dwindling representatives of the older Mesozoic floras.

In the latest Upper Cretaceous floras of this region, that of the Ripley formation, about 40 per cent of the genera are unknown in the earliest Eocene and over 20 per cent are entirely extinct. This clearly indicates that the old and rather widespread impression that with the appearance of a considerable number of angiosperms in the mid-Cretaceous, terrestrial floras were rapidly transformed from a Mesozoic to a Cenozoic facies, and that the "Age of Flowering Plants" started in mid-Cretaceous and antedated the "Age of Mammals" by the whole of the Upper Cretaceous period, is most uncritical. Dramatic statements like the foregoing quotations [[p. 34]] sound well, but are no more exact than the "Age of Algae," or the "Age of Cycads," or any of the other "Ages" that embroider the text in popular scientific writing.

The second great modernization of terrestrial floras marks the dawn of the Cenozoic era--not that this time marked the sudden ringing up of the curtain on a new scene with new actors--there was no cataclysmal cause back of it. Nor was change sudden. Old types of plants had been gradually dropping out and new ones appearing either as a result of autochthonous evolution or by immigration from other centers of evolution, and it suddenly becomes apparent to our limited vision, especially if there is a considerable time interval between the latest Cretaceous and the earliest Eocene sediments, as is the case in the Atlantic Coastal Plain, that we are in a new floral world. In regions like the western interior of North America, or the Mediterranean region of Europe where sedimentation was more nearly continuous, it seems impossible to put one's finger on the boundary between the two periods or to differentiate the floras, and of course if there were complete sedimentary records anywhere, then boundaries, either chronological or organic, would not be discernible.

THE LOWER EOCENE

Aside from scattered and poorly preserved traces of terrestrial plants in the marine sediments of the earliest Eocene of this region, comprising less than a score of genera, the first extensive Tertiary flora is that of the lower Eocene, or Wilcox flora.

Wilcox is the group name for the post-Midway lower Eocene formations--the name coming from a locality in Alabama where they are typically developed and contain fairly distinctive marine faunas that afford a basis for differentiating four formations.4

The Wilcox flora comes from over 130 localities scattered from Alabama to the Rio Grande, developed most extensively along the shores of the Mississippi embayment, which at that time flooded the Mississippi valley northward to the mouth of the Ohio. Between five and six hundred species have been described in 180 genera, 82 families, and 43 orders.

[[p. 35]] The largest families, in the order of their magnitude, are:

Lauraceae Sapotaceae Apocynaceae

Caesalpiniaceae Anacardiaceae Celastraceae

Moraceae Myrtaceae Polypodiaceae

Papilionaceae Combretaceae Arecaceae

Rhamnaceae Juglandaceae Rutaceae

Sapindaceae Sterculiaceae Meliaceae

Mimosaceae Araliaceae

Eighty-three of the genera make their first appearance in the geological record at this time.

This flora is largely coastal and indicates a warm temperate climate and an abundant rainfall, more tropical in its facies than that of the late Upper Cretaceous flora which preceded it in this same region. It shows great contrasts with the contemporaneous floras of the western interior and Pacific slope regions, chiefly in its coastal character, its large representation of equatorial genera and in a relative absence of such northern genera as Populus, Fagus, Corylus, and many others which are so conspicuous in the so-called Fort Union flora and in other western floras of approximately the same age as the Fort Union.

Interest naturally centers in the probable origin of this exceedingly rich flora. As to this it may be said that from the known record the following genera had already attained a Holarctic distribution and were indigenous in southeastern North America at the beginning of Wilcox time:

Acerates Eugenia Persea

Acorus Euonymus Pistia

Amygdalus Euphorbiophyllum Platanus

Anemia Ficus Poacites

Apocynophyllum Fraxinus Potamogeton

Aralia Grewiopsis Proteoides

Asplenium Ilex Prunus

Bumelia Magnolia Pteris

Celastrus Marchantites Rhamnus

Cinnamomum Menispermites Sapindus

Cissites Myrcia Smilax

Crotonophyllum Myrica Sparganium

Cyperacites Nectandra Sterculia

Dalbergia Nelumbo Taxites

Diospyros Nyssa Ternstroemites

Dryophyllum Oreodaphne Zizyphus

Dryopteris Oreopanax

Equisetum Paliurus

Although the foregoing genera were indigenous, many of their species, especially in the more prolifically represented genera, were new products of evolution or were immigrants into this region. [[p. 36]] For example, in the large genus Ficus, only three or four species are considered to have been indigenous, eleven are either new or are invaders from equatorial America, and four were derived from the western United States.

About 60 per cent of the genera, with over 100 species, are considered to have entered the region from equatorial America, either by way of Mexico, the Antilles, or as drift seeds and fruits.

The climatic conditions on the east and west coasts of the Mississippi embayment resulted in considerable differences in the floras along the two shores. Thirty-three genera with 37 species are confined to the western shore, and 148 genera with 354 species are confined to the eastern shore. The plants of the former show a greater resemblance to members of the contemporaneous floras of western North America and to present day floras of Central America; those of the latter are more closely allied to present day floras of northern South America, and presumably entered the region, at least in part, by way of the extended Antilles.

The Wilcox was a time of fluctuating but very shallow seas, even in southern Alabama where the most complete marine section is displayed. In the upper reaches of the embayment there were extensive sand flats, barrier beaches, coastal lagoons and estuaries, interspersed with swamps. It was in the last of these that plant debris accumulated to form the lignites which are so common in the Wilcox from Alabama to Texas, and which in places are sufficiently thick and pure to form the basis of coal mining.

The shallowness of the embayment waters at this time and the vast quantities of fresh water brought in by the master streams, draining practically the whole interior of North America south of the Canadian shield, prevented extension of the marine faunas of the Wilcox beyond the lower part of the embayment.

The Wilcox epoch is brought to a close by a withdrawal of the shallow Wilcox sea, and after a considerable interval, during which the coast line was an unknown distance south of the region, a second northward transgression of marine waters brought about a renewal of sedimentation over a considerable part of the Wilcox area. Sediments of this sea contain representatives of a middle Eocene marine fauna and samples of the contemporaneous terrestrial flora which clothed its shores.

[[p. 37]] THE MIDDLE EOCENE

The middle Eocene formations comprise what is known as the Claiborne group and their equivalents. Aside from petrified wood, the plants from the middle Eocene are much more limited in number and are present (preserved) at fewer outcrops than is the case in the lower Eocene. Claiborne plants are known from only 23 localities, scattered from the Chattahoochee River in Georgia to the Rio Grande region in Texas and northern Mexico.

The total number of known species is only 90 in 66 genera, 34 families, and 24 orders. These comprise a fungus, 6 ferns, 4 gymnosperms, 8 monocotyledons, and 71 dicotyledons. The largest families in the order of their relative importance are the Lauraceae, Leguminosae, Sapindaceae, Arecaceae, Polypodiaceae, Moraceae, Rhamnaceae, Combretaceae, Rutaceae and Celastraceae.

Some idea of the botanical character of the Claiborne flora can be given by an enumeration of some of the genera represented. These are

Acrostichum Fagara Nectandra

Anemia Ficus Nyssa

Bactrites Geonomites Oreodaphne

Carapa Glyptostrobus Oreopanax

Cedrela Goniopteris Persea

Citrophyllum Inga Pisonia

Coccolobis Laguncularia Reynosia

Combretum Lygodium Sapindus

Conocarpus Mespilodaphne Sophora

Copaifera Mimusops Sterculia

Diospyros Momisia Terminalia

Dodonaea Myrcia Thrinax

Eoachras Myrica Zizyphus

The climate appears to have become progressively warmer during Claiborne time, and less than a dozen species of the extensive lower Eocene flora of this region have been detected in the middle Eocene. This reflects, in part, the limited extent of the flora known from the middle Eocene, and emphasizes somewhat the lapse of time between the lower and the middle Eocene times of sedimentation.

Since this middle Eocene flora is so distinctly a warm coastal flora it offers but slight resemblance to the Eocene floras known from other parts of North America, those which show some community being found in the Green River and Bridger basins of [[p. 38]] Colorado and Wyoming; they are of approximately the same age as the Claiborne.

The Claiborne epoch is marked toward its close by a shallowing and ultimately by a considerable withdrawal of the Claiborne sea during which there were widespread accumulations of lignitic deposits in palustrine environments. The time involved in this interval, however, was much shorter than that between the lower and the middle Eocene.

THE UPPER EOCENE5

The sediments of upper Eocene age in the Mississippi embayment constitute the Jackson group of formations. They are inaugurated by a marked transgression northward of marine waters up the Mississippi valley, whose sediments overlap those of the Claiborne sea and extend as far as western Kentucky and northeastern Arkansas.

Recognizable plants of this time have been found from near the Savannah River in Georgia (Grovetown) southwesterly to Webb County, Texas. The number of named species is 133 which is somewhat more than is known from the middle Eocene, but very much fewer than from the lower Eocene, and altogether too few for purposes of either precise correlation or ecological deduction. These comprise 4 fungi, a specimen of Marchantites, 4 ferns, an Equisetum, 2 or 3 gymnosperms, 15 monocotyledons, and 106 dicotyledons. They represent 89 genera in 52 families and 32 orders. The larger families in the order of their importance are:

Lauraceae Sapotaceae Juglandaceae

Leguminosae Rutaceae Nyctaginaceae

Arecaceae Sapindaceae Combretaceae

Moraceae Rhamnaceae Myrtaceae

Thirty-seven of these Jackson species were already present in Claiborne time and continued into the upper Eocene.

The climate in this region is believed to have reached its maximum of geniality during the upper Eocene, or possibly in the succeeding Oligocene epoch, the known flora of the latter being too scanty to permit a decision on this point. Jackson floristics indicate three principal kinds of plant association. These are represented by estuary accumulations with lignites, often of considerable thickness and marking the sites of Acrostichum swamps, this genus being [[p. 39]] especially abundant; or by Mangrove swamps with their border plants (Rhizophora, Conocarpus, Combretum, etc.); or by beach jungle associations (Thrinax, Sapindus, Dodonaea, Pisonia, Sapindus, Terminalia, Fagara, Lygodium, Cedrela, etc.); all along with other plant types of no certain provenance. Petrified palm wood is especially abundant in the Jackson and is perhaps only a correlative of the prevailingly sandy nature of the deposits in the non-marine part of the area of outcrop, e.g., in the Texas region.

Plant genera present which subsequently became extinct in North America include the date-palm (Phoenicites), represented by broken rays and characteristic seeds in hard fruits; Engelhardtia, that curious genus of the Juglandaceae with winged fruits, restricted in modern floras to a single species in Central America which is sometimes made the type of a distinct genus, and to a dozen or more oriental species in the southeastern Asiatic region; characteristic fruits and seeds of nutmeg (Myristica); fruits of the Nipa-palm (Nipadites), now monotypic on tidal shores from India to the East Indies, but almost world-wide in the early Tertiary; twigs of what has been identified as Glyptostrobus, now monotypic in eastern China; and other and less spectacular genera.

During upper Eocene, and possibly extending into Oligocene time, there occurred the greatest northward extension of floras from equatorial America. In common with the earlier Tertiary floras of southeastern North America they appear to be more closely related to the existing flora of northern South America than to those of Central America or the Antilles, and it is believed that subsequent restriction of land areas in the Antilles is one of the reasons for this. Unfortunately, paleobotanical knowledge of all of equatorial America before the later Tertiary is practically non-existent.

This northern extension of equatorial forests alluded to in the preceding paragraph appears to correspond in time to the great polar extension of temperate floras into the Arctic region and possibly into the Antarctic as well (Seymour Island), happenings, the discovery of which awakened an interest that has continued unimpaired through several generations and is still the subject of frequent discussion and a still greater amount of misunderstanding.

It is believed by many, including the present writer, that, following the world-wide submergence of continental areas and the opening of free seaways between equatorial and Arctic oceans during [[p. 40]] the middle Eocene, the North polar ice cap (the Antarctic, being a region of land and not ocean as is the Arctic, can not safely be included in this statement) was greatly reduced or disappeared altogether. The subject is too complex to be more than referred to in the present abstract, but the reader is not to misunderstand what has been said. These polar floras do not indicate uniform or tropical climates and a lack of climatic zones, and the numerous statements of such conditions that are contained in the literature are false.

The following bit of evidence, confirmatory of the interpretation given in the present paper, is worth recounting. A considerable number of Miocene floras are known from Cuba, Hayti, Porto Rico, Trinidad, southern Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, Venezuela, and Colombia, and only a single Eocene flora in the whole region. This last is in Venezuela and, though extremely limited, it contains several types which are identical, even as to species, with those of the upper Eocene of the Mississippi embayment, whereas the widespread and much more extensive Miocene floras from equatorial America are wholly unlike those of the United States. One is, I think, justified in the belief that the interpretation is sound and that it would be confirmed if more were known of the older Tertiary paleobotanical history of equatorial America.

Returning more closely to the theme of the present paper, it may be noted that Eocene fossil plants northeast of the embayment region comprise an occasional fruit or seed in the marine deposits of Maryland and Virginia, and those from the isolated and unique lignitic basin at Brandon, Vermont. The Aquia and Nanjemoy formations, highly fossiliferous marine deposits in tidewater Maryland and Virginia, contain occasional drift fruits brought in by rivers from the adjacent mainland. The most abundant of these, resembling some of the forms from Brandon, Vermont, goes by the botanically nondescript name of Carpolithus marylandicus, and its botanical affinities remain to be discovered. Recently, a pine cone and a beautifully preserved woody fig fruit have been described from these deposits.6

The Brandon, Vermont, plants constitute a curious assemblage of fruits and seeds--long known and discussed in the earlier days [[p. 41]] of American paleobotany by Hitchcock (1853), Lesquereux (1861), Knowlton (1902) and others. Attempts to utilize these lignites for fuel during a coal shortage a generation ago led to the discovery of a very large amount of new material which was described by the late George H. Perkins, who for so long was State Geologist of Vermont. Although somewhat over-elaborated specifically, his work affords, nevertheless, a most interesting, and in fact the only, glimpse of the flora of New England during any part of the Tertiary.7

The Brandon flora was long thought to be of Miocene age, this age, for reasons that need not be enumerated here, having also been assigned to the Arctic fossil floras and to those of the western interior of North America, and even to those of the Mississippi embayment, all of which have subsequently been shown to be Eocene in age. The general climatic considerations that have been enumerated, the dissimilarity of the Brandon plants to known Miocene floras and climates, and the similarities and in several cases the identities between Brandon plants and those of the Wilcox, clearly show it to be Eocene.

Although the identical species are chiefly those of the Wilcox, this is regarded as due to the fact that the Wilcox flora is so much more extensive than those that are known from the Claiborne and Jackson, and was probably the source from which many of the Brandon plants spread to Vermont during the northward spread recorded in the middle and upper Eocene. My own opinion is that the Brandon deposit is of upper Eocene age;8 a comparison of the Brandon plants with the recent flora of Vermont or with the flora known from the Miocene of Maryland and Virginia, altogether precludes a Miocene age.

About 175 so-called species from Brandon have been described. The bulk of these are based upon fruits and seeds, although 2 or 3 woods have been described. Leaves have been found but these are poorly preserved and none capable of identification has been discovered. As will be seen from the appended list of genera many are form-genera whose relationship to recent genera has remained entirely problematical, although various students from Lesquereux's time onward have searched through collections of recent carpological material.

[[p. 42]] The following genera have been enumerated and the names will give sufficient indication as to which are form-genera of unknown affinity, which are supposedly related to living genera, and which belong to living genera:

Apeibopsis Drupa Pinus

Aristolochia Hicoria Pityoxylon

Aristolochites Hicoroides Prunoides

Bicarpellites Illicium Rubioides

Brandonia Juglans Sapindoides

Carpites Laurinoxylon Sclerotites

Glossocarpellites Lescuria Staphidoides

Cinnamomum Monocarpellites Tricarpellites

Cucumites Nyssa

THE OLIGOCENE

In eastern North America recognizable Oligocene sediments are confined to the southern states. Southwest of eastern Louisiana these sediments are almost entirely continental in character and thus far have yielded no fossil plants except petrified wood.

In Mississippi the Jackson epoch is terminated by a littoral sandy formation known as the Forest Hill sand which contains a few fossil plants intermediate in character between the upper Eocene and the Oligocene, and it is believed that this sand was partly contemporaneous with the uppermost Jackson and the lower Vicksburg marine sediments.9

East of the Mississippi River the Vicksburg, which is the group name for the Oligocene formations of the region, consists almost wholly of marine sediments, but that there was considerable oscillation of the strand at the close of the Eocene is indicated by the lignites which are often present at the base of the Vicksburg.

Since so much of the Oligocene is marine, and fossil plants are rare or have remained undiscovered in the western outcrops of continental materials, the known flora is exceedingly meager. About a dozen Jackson species are known to continue into the Oligocene, and petrified palm wood is especially abundant. The general facies of the Oligocene flora,10 if the few known species can be relied on for such a generalization, is much the same as that of Jackson time, i.e., a subtropical strand flora. Prominent members of the known flora are species of

[[p. 43]]

Acrostichum Mimosites Palmoxylon

Apocynophyllum Myrcia Pisonia

Fagara Oreopanax Sabalites

Ficus Paliurus

Lygodium Palmocarpon

THE MIOCENE

Marine deposits of Miocene age, often with extensive marine faunas, are found from New Jersey southward, but, except for drift-wood or an occasional water-logged fruit or seed, they rarely contain identifiable traces of the vegetation which clothed the land. Consequently, our present knowledge of the Miocene floras of eastern North America is deplorably unsatisfactory when compared with what is known of the flora of this age in western North America or in Europe.

At Alum Bluff on the Apalachicola River in central Florida and near Hattiesburg in southern Mississippi we get a glimpse of the flora that flourished in those regions at the beginning of Miocene time.11 The first of these is especially interesting, even though the variety of plants is limited, since at this locality there is preserved a fragment of the coast just as it was emerging from the sea. The littoral sands are packed in places with the frayed and tangled rays and stipes of a fan-palm, and the shores were evidently covered with palmetto swamps or brakes. Other plants represented are beach plants, and others apparently came from the shores of nearby bayous. As far as it is known this flora would find a congenial habitat at the present time in the delta of the Apalachicola River or almost anywhere along the coast of peninsular Florida. This statement will give a fair idea of the predicated physiography and climate.

Beginning with the Cenozoic we have seen a long interval lasting through the Eocene and into the Oligocene during which the prevailing direction of plant dispersal was northward from equatorial America, which movement penetrated and largely replaced the temperate types which had inhabited the region during the Upper Cretaceous. At Alum Bluff and Hattiesburg we see for the first time the beginning of a reversal in the prevailing direction of this movement, for at these localities a few equatorial types linger, but these are apparently being replaced by temperate types coming in from the north.

[[p. 44]] Although the evidence is confessedly incomplete, it seems clear that this reverse movement had probably been going on for a short time, and that it continued on a large scale for a considerable time. This is indicated by the presence at the base of the Alum Bluff section of a warm-water marine fauna in a formation known as the Chipola marl and by a marine submergence following the emergence chronicled in the plant bed. This submergence is chronicled by a formation toward the top of the bluffs known as the Choctawhatchee marl, containing a marine fauna like that found in the Chesapeake group of Maryland and Virginia, which fauna is a distinctly cooler-water fauna than that of the Chipola. This conclusion is indicated also by the fact that the only Pliocene flora that is known from this region--that known as the Citronelle in western Florida and southern Alabama--is wholly modern in character.

The Alum Bluff-Hattiesburg early Miocene flora is not extensive, the genera represented being:

Artocarpus Fagara Sabalites

Bumelia Nectandra Sapotacites

Caesalpinia Pestalozzites Ulmus

Cinnamomum Pisonia

Diospyros Rhamnus

The only additional Miocene plants known from eastern North America, except marine diatoms whose frustules make up heavy beds of certain localities, are those which occur sparingly in the near shore deposits of the marine Chesapeake group which are of early middle Miocene age. Determinable leaves have been found at but two localities, one in the suburbs of Richmond, Virginia, and the other in the District of Columbia just southeast of Washington. Both are in the Calvert, the oldest formation of the Chesapeake group.12

The plants found at Richmond clearly indicate that the coast was low and was lined at this point with estuary cypress swamps, Taxodium being the most abundant type represented. Other genera more sparingly preserved at this locality are

Carpinus Nyssa Rhus

Celastrus Planera Salix

Ficus Platanus Salvinia

Fraxinus Quercus Ulmus

[[p. 45]] Those found in the District of Columbia appear to be, for the most part, plants of coastal dunes, mixed with river-borne drift, and include Berchemia, Cassia, Ilex, several small-leafed oaks, cypress twigs, seeds of a pine, Pieris, Rhus, and various leguminous leaflets. Elsewhere the Calvert formation has furnished an occasional pine cone, cherry stone, acorn or walnut. Generically, all of these are very modern but several of the species are very similar to or identical with species from the middle Miocene of other regions. Climatically, these middle Miocene plants from Maryland and Virginia would be at home at the present time at almost any suitable locality south of the Potomac River, and I have visited many localities from the coast of North Carolina to Alabama that support a rather similar plant assemblage.

A considerable flora is known, but has never been described adequately, from beds in southern New Jersey that are known locally as the Bridgeton sandstone, from the town of that name near which they were found.13 These have been variously considered to be late Miocene or Pliocene in age. Their similarity to the plants found in the Pleistocene Pensauken formation of New Jersey appears to indicate that they also are Pleistocene in age, and hence outside the scope of the present paper.

THE PLIOCENE

Highly fossiliferous marine formations of Pliocene age are found in the Carolinas, in Florida, and at a few other localities near the present coast, but no land plants have been discovered in them. As was the case during the Miocene, little is known of the Pliocene floras of eastern North America as compared with our knowledge of floras of this age in western North America or Europe.

The only considerable Pliocene flora known from the whole Atlantic region, and that not an extensive one, has been found in the clays of what is known as the Citronelle formation in western Florida and southern Alabama.14

Eighteen species have been determined from these outcrops. The genera represented are:

[[p. 46]] Betula Hicoria Quercus

Bumelia Nyssa Taxodium

Caesalpinia Pinus Trapa

Fagus Planera Vitis

Fraxinus Prunus Yucca

The bald-cypress, water-oak and water-elm still exist in the region but the remainder are represented by extinct species. These are practically all similar to still-existing species of the mesophytic forest region of the southeastern United States except Trapa which no longer is a native of North America.

This Pliocene flora is comparable in a broad way with the existing flora of the same region. The forms thus far known are such as are found in modern times in cypress ponds, around coastal lagoons and with a sprinkling of forms found in live-oak thickets. It is concluded that the climate could not have been appreciably different from that which prevails in southern Alabama at the present time.

_________________________

Notes Appearing in the Original Work

1. So little is known of the floras

of the Quarternary period in eastern North America that the present discussion

is limited to the Tertiary period. [[on p. 31]]

2. Taken from Barrell's estimates based upon radioactivity.

U. S. Geol. Survey Bull. 769: 5. 1925. [[on p. 31]]

3. Taken from Barrell's estimates based upon radioactivity.

U. S. Geol. Survey Bull. 769: 5. 1925. [[on p. 33]]

4. Berry, E. W. U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 156.

1930. [[on p. 34]]

5. Berry, E. W. U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 92.

1924. [[on p. 38]]

6. Berry, E. W. Jour. Wash. Acad. Sci. 24:

182-183. 1934; 26: 108-111. 1936. [[on

p. 40]]

7. Perkins, G. H. Rep. State Geol. (Vermont) for 1903-1904;

1905-1906. [[on p. 41]]

8. Berry, E. W. Am. Jour. Sci. 47: 211-216.

1919. [[on p. 41]]

9. Berry, E. W. U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 92:

96. 1924. [[on p. 42]]

10. Berry, E. W. U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 98:

227-251. 1916. [[on p. 42]]

11. Berry, E. W. U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 98:

41-59. [[on p. 43]]

12. Berry, E. W. U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 61-73.

[[on p. 44]]

13. Hollick, A. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 19:

330-333. 1892; 23: 46-49. 1896; 24:

229-231. 1897. [[on p. 45]]

14. Berry, E. W. U. S. Geol. Survey, Prof. Paper 98:

193-208. 1916. [[on p. 45]]

*

*

*

*

*