HISTORY 241

CLASS INSTRUCTIONS

FALL 2007

Marion B. Lucas

Professor of History and

University Distinguished

Professor

Office CH 224-B

Office Ph. (270) 745-5736

Office Fax (270) 745-2950

Home Ph. (270 843-8580

E-mail: marion.lucas@wku.edu

WKU History Department Home

Page

Hist

241 [CRN 35228] Room: CH 239 CLASS

INSTRUCTIONS M. B. Lucas CH

224-B

Each student must spend at least six

(6) hours in preparation for each weekly class assignment.

1.

Text: Roark, James L., et al., The American Promise: A History

of the American People. Vol. II: From 1865. Boston & New York:

Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2005. ISBN: 0-312-40689-4 (Vol. II) Mary Lynn

Rampolla, A Pocket Guide to Writing in History (2007, 4th or 5th

edition; optional)

2. Tests:

All hour tests are written in INK in BLUE BOOKS. You can purchase Blue

Books at the book store. There will be two (2) essay hour tests, each

counting 1/5 (20% each) toward the final grade. The hour tests will

cover the lecture material and will not be cumulative. The final exam,

which counts 2/5 (20%) toward the final grade, will be comprehensive.

Essays and identifications on the hour tests are graded with regard to

content and writing style. This means that there is an "X-factor"

involved. The student must state all answers clearly, in a coherent,

logical manner. Ideas and concepts are always important. If you have

any questions regarding your grade, you should come to my office and

inquire. Please do not wait until the last week of classes.

3. Pop

Tests: There will be twelve (12) pop quizzes. They will come

from the text assignments (see assignment sheet). These quizzes count

1/5 (20%) toward the final grade. The two (2) lowest pop quiz grades

will be dropped. If you miss a pop quiz, that counts as a dropped grade.

4. Research

Paper: The research paper counts 1/5 (20%) of your grade. To be

announced.

5. Absences

and Excuses: There will be no make-up tests without a written

excuse. It is your responsibility to see me regarding absences. You are

allowed one (1 night equals 3 classes) excused absence. Missing the

equivalent of nine (9) class hours constitutes a failure. You will be

required to hand in a written text assignment after your first absence.

6. Grading

scale: 90-100 = A / 80-89 = B / 70-79 - C / 60-69 =

D / 0-59 = F

7. Honor

System: Each student is expected to be on his or her honor

regarding to all work. Dishonest activity and plagiarism will lead to a

reduction of one's grade.

8. Parallel

Reading: You must read one (1) book on American history outside

of class. The book must be on topics that discusses some aspect of

American history before 1865. You will have to write a three to four (3

to 4) page review-analysis of the book you read. Use the following

format: Place your name and page number in the upper right-hand corner

of your page. Cite your book as example given below on the top line (no

cover sheets):

Catton: Bruce. A Stillness at Appomattox. Garden

City, N. J.: Doubleday & Company, 1954.

The first paragraph of the Review should provide

biographical information on the author. The review should give the

thesis of the author; that is, you should describe the point the author

is trying to make. You should give some examples of how he or she makes

the point and then you must write your own evaluation of the book (see

my web site Study Suggestions

[http//www.wku.edu/~marion.lucas/study.html] & Rampola, Writing in

History for more on the book report)

9. Cultural

Assignment: You are required to attend four (4) cultural events

during the semester. Please write and hand in to me a one-paragraph

statement on events you attend as you attend them. The Events Calendar:

http://www.wku.edu/Dept/Support/AcadAffairs/pag9.htm will help you find

cultural events to attend.

11. In compliance with university policy, students with

disabilities who require accommodations (academic adjustments and/or

auxiliary aids or services) for this course must contact the Office for

Student Disability Services in DUC A-200 of the Student Success Center

in Downing University Center. Please do not request accommodations

directly from the professor without a letter of accommodation from the

Office for Student Disability Services.

Each student is expected to spend at least two (2)

hours in preparation for each class assignment. During study,

certain purposes should be kept constantly in mind. (1) Facts

must be mastered. The study of history is hard memory work.

Names, dates, terms, and similar data are basic. It is assumed

that the student will master the facts in each text assignment and

lecture. It is impossible to draw correct conclusions about

events in history if you do not know the facts of the event. (2)

The idea or theme of each chapter should be acquired. Be sure

that the material in each paragraph can be written in your own words

before leaving it. (3) These steps, however, are merely

preliminary to the final purpose of the course which is to allow each

student to become his or her own historian. That is, you must

learn to interpret America's past for yourself. To accomplish

this end, the student should constantly keep in mind how the most

important institutions and ideas have originated, and how our strong

points and weaknesses have developed.

Students often ask me, "How is all this to be

accomplished?" Frankly, there is no one way for a professor to

tell a student how to study. Yet, there are certain methods that

students might employ to enable them to do their best on each

assignment. First, it is suggested that the student go through

the assigned pages rather hurriedly, reading each heading.

Secondly, the student should read each heading and the first and last

sentence of each paragraph. The purpose of this scanning is to

give the student the scope and content of the entire assignment.

This can be accomplished in about five (5) to ten (10) minutes!

Thirdly, the assignment should be read thoroughly, with proper

attention to maps and pictures. Important facts and the theme of

each paragraph should be noted by underlining, or writing in the book

margins or on a separate piece of paper. This third process can

be completed in forty-five (45) to seventy-five (75) minutes per

assignment.

This brings us to the fourth step, that of study and

reflection. You should not pass on to the next paragraph until

you are able to summarize what you have learned in your own

words. This will consume thirty (30) to forty-five (45) minutes

per assignment. The remaining fifteen (15) to thirty (30) minutes

of the time allotment should be spent on the parallel reading or

studying for the hour tests.

Each student is required to take lecture notes in

class; the hour tests and the final are based upon the lecture

material. You must develop your own method of taking notes.

Do not try to take down every word, but rather train your ear to hear

the main points. Remember, the better your notes, the better you

will do on the hour tests. If you miss something, leave a blank

space in your notes to be filled from the textbook after class.

The lecture notes should be reviewed regularly and preparations for an

hour test should begin at least a week before the test.

It is the student's responsibility to know the

location of the professor's office and posted hours. If you

encounter any difficulty which cannot be solved by application, consult

with the professor, either during regular office hours or by special

appointment. Do not wait until the end of the semester or until

you receive an invitation to the instructor's office.

The Lincoln Memorial,

Washington,

D.C.

Slide by M.B. Lucas

Slide by M.B. Lucas

"With Malice Toward None."

HISTORY 241

CLASS ASSIGNMENTS

FALL 2007

5:15-8:15 Tuesday

M. B. Lucas CH 224-B

Ph. (270) 745-5736

Email: marion.lucas@wku.edu

Home page: www.wku.edu/~marion.lucas

Each

student must spend at least six (6) hours in preparation for each class.

Text: Roark, James L., et al., The American Promise: A History of the

American People. Vol. II: From 1865. Boston & New York: Bedford/St.

Martin’s, 2005. ISBN: 0-312-40689-4 (Vol. II); Mary Lynn

Rampolla, A Pocket Guide to Writing in History (2007, 4th or 5th

edition; optional)

DATES-----CHAPTER ASSIGNMENTS

Aug. 28------Instructions & Lecture

Sept. 4-–----Chapters 16 & 17

Sept. 11------Chapters 18 & 19 [Research paper topic decision]

Sept. 18------Chapter 20 [Preliminary research paper bibliography due]

Sept. 25------Chapter 21 [Research paper discussion]

Oct. 2---------FIRST HOUR TEST

Oct. 9---------Chapters 22 & 23 [Research paper note cards due]

*Oct. 16–-----Chapter 24 [last day to drop with a “W”; do not drop

before contacting the professor]

**Oct. 23-----Chapter 25 [Book report-analysis due]

Oct. 30--------Chapter 26

Nov. 6---------SECOND HOUR TEST

Nov. 13-------Chapters 27 & 28

***Nov. 20---Chapter 29 [Research Paper due]

Nov. 27-------Chapter 30

****Dec. 4---Chapter 31

FINAL EXAM: December 11, Tuesday, 6:00 to 8:00 p.m.

IMPORTANT DATES:

*Oct. 16----Last day to with "W"; do not drop before

contacting the professor

**Oct. 23--Book report-analysis due

***Nov. 27–Research Paper due

****Dec. 4--Last day to turn in Cultural Assignments

HISTORY 241 RESEARCH PAPER TOPICS

- Fall, 2007, M. B. Lucas

Who won the Civil War?

Reconstruction: Did it help or hurt the South?

Did Reconstruction Change Anything?

The Redeemers

Reconstruction: Bad or Good?

Impeachment in the U.S.: Does it Work?

The Freedmen’s Bureau in Kentucky: Success or Failure?

The Settlement of Blacks on Abandoned Lands: Good or Bad?

The Failure to Secure Civil Rights for Blacks: Who Was Responsible?

The Disputed Election of 1876: Theft or Democratic Processes at Work?

Kentucky’s Black Migration to Kansas: Why?

U. S. Post-Civil War Industrialization: Free Market or Monopoly?

Social Darwinism v. the Gospel of Wealth

Industrialists: Free Market Giants or Free Market Opponents?

Ida B. Wells and the Fight Against Lynch Law

Temperance: Success or Failure?

Tariff Policy: Important Policy or a Political Football?

Why American Conservatism: Status Quo or Progress?

Free Silver: Financial Solution or False Dream

The Old South and the Old West in American Memory

Immigrants: A Plague in the Land or America’s Future Leaders?

Sweatshop Workers: Lucky to Have a Job or Exploited?

Strikes: Criminal or Legal?

The Populist Revolt: Success or Failure?

The Vote for Women: Why the Controversy?

Coxey’s Army: Good Idea or Bad Idea?

Child Labor: Inherit Right or Exploitation?

U. S. Diplomacy 1890-1914: Economic or Idealistic?

The KKK of the 1920s: Heritage or Hate?

The U. S. Army in World War I: Prepared or Unprepared?

World War I: Truth v. Propaganda

Prohibition: Good or Bad?

Clarence Darrow v. William Jennings Brian & the Scopes Trial: Who

won?

Herbert Hoover: Great Economic Thinker or Blind Idee Fixe?

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Saved Capitalism or Creeping Socialist?

The New Deal: Good or Bad for America?

Free Market Economy: Myth or Reality?

Huey Long: Reformer or Demagogue?

The U. S. A.: Capitalist or Welfare State?

American Neutrality in World War II: Good or Bad?

FDR’s Arsenal of Democracy Policy: Neutrality or War?

Pearl Harbor: What Went Wrong?

Loss of the Philippines: Who Was Responsible?

Interning the Niesei: Responsible Government or Mistaken Policy?

U. S. World War II Home Front: Rationing or Not?

Anti-Semitism in Wartime America: Real or Imagined?

Yalta: Sellout or Rational Policy?

The Atomic Bomb: Was it Necessary?

Jackie Robinson and his Role in Desegregation: Success or Failure?

Harry Truman: Contained Soviet Expansion or Created the Cold War?

McCarthyism: Patriotism or Politics?

Consumerism: Good or Bad?

Dwight D. Eisenhower: Political Thinker or Puppet?

Richard Nixon: Man of Ideas or Troubled Soul?

The Brown Decision: Timely or Too Late?

Modern American Liberalism: Improbable Dream or Realistic Progress?

Lyndon B. Johnson and the Great Society: Success or Failure?

Southern Desegregation: Caused by Internal Protests or Northern

Pressure?

The Counter Culture: Real Issues or Boys & Girls Just Want to Have

Fun?

Lyndon B. Johnson and the Viet Nam War: What was the Problem?

Feminism: Legitimate Movement or Irrational Provocateurs?

Viet Nam: Good Idea or Bad Policy?

U. S. Caribbean Policy: Good or Bad?

The Republican Party in the South: Racism or Real Change?

School Bussing in Boston: Racism or Just the “South” part of “South

Boston”?

Jimmy Carter’s Human Rights Policy: Good or Bad?

Ronald Reagan: Genuine Conservative or Tool of the Wealthy?

The Equal Rights Amendment: Good Idea or Bad?

The Homeless: Get a Job or National Social Problem

Evacuating Viet Nam & Iraq: Similarities & Differences?

Sioux Chief Red Cloud

PDImages.com

Sioux Chief Red Cloud

fought

to preserve the Buffalo range.

Footnote Style for

History Courses

Students

must use the proper history method for footnotes, endnotes, and

bibliography

citations. The Modern Language Association (MLA) is not

acceptable. For

the current citation style, peruse the latest edition of The Chicago

Manual of

Style, located in Helm-Cravens Library, and note citations of the

leading

historical journals.

Papers

should always have a title page, footnotes or endnotes, and a

bibliography. Papers must be printed double-spaced in letter

quality type.

Right margins must be ragged. Pagination options: (1)

the

first page number at the bottom center of the first page of text; all

page

numbers thereafter must be in the upper right corner through the

bibliography,

or (2) place all page numbers in the upper right corner beginning with

the

first page of text and continuing through the bibliography.

Papers

consisting of undetached computer paper are unacceptable.

The

following are samples of the required footnote and bibliography

citations for

all history papers:

Books

In a note:

1Lowell H.

Harrison, John Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican

(Louisville,

Ky.: The Filson Club, 1969), 28.

2Marion B.

Lucas, Sherman and the Burning of Columbia (Columbia, S.C.:

University

of South Carolina Press, 2000), 170.

Second

Citing, Short Form of a previously

cited work (separated by another work):

3Harrison, Breckinridge,

29.

4Ibid., 41. (Use

ibid or ibid when citing the same work used in

the previous footnote in all instances except multiple citation notes.)

In the bibliography:

Harrison,

Lowell H. John

Breckinridge: Jeffersonian Republican. Louisville, Ky.:

The

Filson Club, 1969.

Articles

In a note:

1Patricia

Hagler Minter, “The Failure of Freedom: Class, Gender, and the

Evolution of

Segregated Transit Law in the Nineteenth-Century South,” Chicago-Kent

Law

Review 70 (1995): 993-1009.

2Robert

Dietle, “William S. Dallam: An American Tourist in Revolutionary

Paris,” The Filson Club History Quarterly 73

(1999): 139-65.

Second

Citing, Short Form of a previously

cited work (separated by another work):

3Minter, “The

Failure of Freedom,” 1002.

4Ibid.,

1008. (Use ibid or ibid

when citing the

same work used in the previous footnote in all instances except

multiple

citation notes.)

In

a bibliography:

Minter,

Patricia Hagler. “The

Failure of Freedom: Class, Gender, and the Evolution of Segregated

Transit Law

in the Nineteenth-Century South.” Chicago-Kent Law Review 70

(1995):

993-1009.

Newspapers

In a note:

1New

York Times, January 23, 1865.

2The Columbia (S. C.) Record,

February

17, 1865.

3New

York Tribune, December 26, 1859.

Second

Citing of a previously cited work

(separated by another work):

New York Times, September 9, 1877.

4Ibid.,

January 5, 1865. (Use ibid or ibid

when

citing the same work used in the previous footnote in all instances

except

multiple citations.)

In the bibliography:

New York Times, 1865-1877.

Manuscripts

In a note:

1John

A.R. Rogers Diary, I, August 27, October 8, 1862, Founders and

Founding, Box 8,

folder 7, Record Group 1, Berea College Archives, Berea, Kentucky.

2Diary of

Eldress Nancy, February 13, 1863, South Union Shaker Records,

Department of

Library Special Collections, Manuscripts, Western Kentucky University,

Bowling

Green, Kentucky.

3John F.

Jefferson Journal, November 23, 1862, John F. Jefferson Papers,

Manuscript

Division, Filson Club, Louisville, Kentucky.

4Hattie

Means to mother, January 14, 1863, Means Family Papers, Margaret I.

King

Library, Special Collections, University of Kentucky, Lexington,

Kentucky.

Second

Citing, Short Form of a previously

cited work (separated by another work):

5John Rogers

Diary, October 8, 1862, Founders and Founding.

6Diary of

Eldress Nancy, February 13, 1863, South Union Shaker Records.

7John F.

Jefferson Journal, October 31, 1862, John F. Jefferson Papers.

8Hattie Means to

her mother, February 17, 1863, Means Family Papers.

9Ibid.,

January 5, 1864. (Use ibid or ibid

when

citing the same work used in the previous footnote in all instances

except

multiple citation notes.)

In a bibliography:

John A.R. Rogers. Diary, Founders and

Founding, Berea College Archives,

Berea, Kentucky.

Moore,

Eldress Nancy.

Diary. South Union Shaker Records. Department of Library

Special

Collections, Manuscripts, Western Kentucky

University,

Bowling Green, Kentucky.

Jefferson,

John F. Journal. John

F. Jefferson papers, Manuscript Division, Filson Club, Louisville,

Kentucky.

Means

Family Papers.

Margaret I. King Library, Special Collections, University of Kentucky,

Lexington, Kentucky.

Documents

In a note:

1The War of

the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union

and

Confederate Armies (128 vols., Washington: Government

Printing

Office, 1880-1901), Ser. I,

Vol. 4, 396-97, hereafter cited Official Records.

2U.

S. Report of the Commissioners of the

Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands for the Year 1867. Washington, D. C., 1867.

Second

Citing, Short Form of a previously

cited work (separated by another work):

3Official

Records, Ser. I, Vol. 88, Part I, 199-202.

4Ibid.,

Ser. II, Vol. 2, Part II, 21. Use

ibid or ibid

when citing the same work used in the previous footnote in all

instances except

multiple citation notes.

In

a bibliography:

U.S.

The War of the

Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and

Confederate

Armies. 128 vols. Washington: Government Printing

Office,

1880-1901.

Web Cites

Currently, no standard

exists. However, your citation should be clear, complete, and

easily

followed. See Mark Hellstern, Gregory M. Scott, and Stephen M.

Garrison,

The History Student Writer's Manual (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice

Hall,

1998) for suggestions.

HISTORY WEB CITES OF

INTEREST

American

Memory Historical Collections for the National Digital Library

Avalon

Project at the Yale Law School

The

American Civil War Homepage

American

Studies Web

Cold

War International History Project

Documenting

the American South: Beginnings to 1920

H-CIVWAR

Home Page

H-Net:

Humanities & Social Studies OnLine

H-South:

The History of the American South

Historical

Text Archive

History

Links on the Internet

History

Resosurces on the Internet

The

History Ring

A

Hypertext on American History

The

Idea of the South: Electronic Resources

John

Brown and the Valley of the Shadow

Making

of America: University of Michigan

Making

of American: Cornell University

NYPL

Digital

Library Collections

Old

Dominion University Library Digital Services Center

Social

Sciences Virtual Library

The

Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War

Voice

of the Shuttle: History Page

U.S.

Civil War Center-Index of Civil War Information available on the

Internet

World

War II Resources

The

World Wide Web Virtual Library: History

The

Book Review Tutor

American

Historical

Association

Organization

of American Historians

Southern

Historical Association

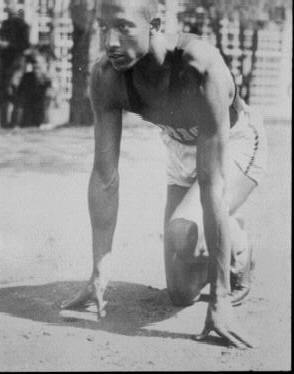

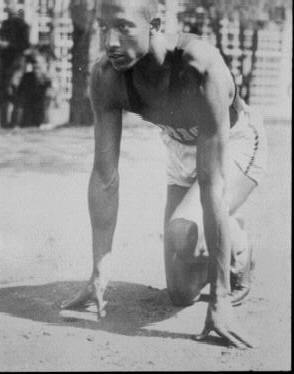

Jesse Owens

PDImages.com

In the 1936 "Nazi" Olympics Ohio State

University

track star, Jesse Owens, won in spite of unfair officiating designed to

give "Aryan" runners victory.

VOCABULARY AND HISTORY

Language is essential, even vital for the study

of

history. Purchase a good dictionary. I recommend Webster's

New World Dictionary (latest edition). I also

recommend

that you purchase, and keep with you when studying or writing, Shirley

M. Miller, comp., Webster's New World

33,000

Word Book (latest edition). This book will give

you

the correct spelling and dividing of most-used words. To improve

your vocabulary, I recommend purchasing a vocabulary study book such as

Norman Lewis, Word Power Made Easy

(latest edition) or Wilfred Funk and Norman Lewis. 30

Days to a More Powerful Vocabulary (latest edition)

and,

of course, retain your English grammar book for reference. Such

works

will enable you to improve your vocabulary significantly. I

suggest

that you approach vocabulary study systematically. Decide on a

plan

such as learning one new word a day, or perhaps more practically, three

words a week. Once you develop a plan which works for you, stick

with it.

One more tip. Learn the key rules of grammar this

semester. Know the difference between plurals and

possessives.

Know what a comma splice is. Learn the proper use of the

apostrophe.

And remember: commas and periods are always inside quotation marks, [,"

or ."] and colons and semicolons are always outside

quotation

marks ["; or ":]. Learn

these

simple rules and you will eliminate 90 percent of the most typical

errors

made in grammar. One more suggestion. Look up "topic

sentence"

in your grammar book and review the ideas suggested for writing

them.

And by

the way, "a lot" is two words, not one!

WORDS YOU SHOULD

KNOW:

VOCABULARY FOR HISTORY 241

abated, abrogate, acrimonious, adamant, adulation, aegis,

aesthetics,

affable, affluent, aggrandize, aggregate, alleviation, amiable,

ambiguous,

ambivalent, amenable, amoral, amphibious, analogy, anonymity,

antebellum,

antediluvian, anti-clerical, antipathy, appeasement, articulate,

assiduous,

assuage, astute, austere, autonomous, avarice, baroque, bellicose,

blatantly,

bombastic, bulwark, capitulate, capricious, caricature, cataclysmic,

cause

célèbre, cholera, clandestine, cogent, collaborate,

complicity,

conciliation, concordat, condoned, congenial, consternation,

contiguous,

convivial, coterie, coup d'état, covenant, credibility,

crucible,

dauphin, dearth, debacle, debilitated, debilitating, decorum, defame,

deistic,

delineate, demographic, derisively, despot, détente, deterrent,

devotion, didactic, diffidence, diffusion, dint, discursive, disparage,

doggedly, dogmatism, dogmatist, doldrums, dole, dragoons, duplicity,

egalitarian,

egregious, electorate, elegy, elucidate, emanate, emancipate,

empirical,

emulators, enigmatic, enmity, entities, enunciated, epitomize,

eschewed,

estrangement, ethereal, ethics, euphemism, euphoria, exchequer,

expropriation,

extralegal, fait accompli, feints, fetters, flagrant, fledgling, flout,

fluctuation, foment, freemason, galvanize, garner, hegemony, hierarchy,

ideological, impecunious, imperious, impetuosity, impetus, impinged,

inculcate,

incumbent, indelible, indemnification, indemnity, indigenous,

ineptitude,

ineptitude, ineptitude, ineptly, inequities, inexorable, inextricably,

inimical, innate, insidious, instigators, interregnum, intransigent,

intrusion,

intuition, irony, irrational, laissez faire, lucrative, ludicrous,

machinations,

maldistribution, melee, mercurial, metaphysics, meticulous, monograph,

moot, mundane, neoabsolutism, nominal, oligarchy, opulent, oscillated,

palatable, palpably, paradoxical, paternalism, patriarch, patronage,

paucity,

pecuniary, penchant, perfidy, perfunctory, prerogative, perquisite,

philanderer,

pietist, pilloried, pinnacle, plausible, plebiscite, pluralism,

plurality,

polemics, posthumous, postulate, preclude, preemptive, prerogative,

prig,

pristine,

prodigy, profligate, promulgated, propound, proscribe, protectorate,

protracted, purveyor, putsch, quelling, rabid, rapprochement,

rationality,

recalcitrant, recapitulate, refractory, refractory, reminiscent,

remunerate,

residue, resilience, retrograde, reverberations, rigid, rudiments,

sagacious,

scandal, sectarian, secularism, seminal, servitude, sovereignty,

spawned,

spurn, status quo, sumptuary, superannuated, supranational, syllogisms,

syndicates, synonymous, tantamount, technocrats, tempering, temporize,

tercentenary, titular, touchstone, transcendence, transcendental,

trauma,

traumatic, tremulous, truculent, tutelage, ubiquitous, ulterior,

unabashed,

unicameral, unpalatable, usurpation, vagrancy, veneer, verbiage, verve,

vilify virile, vituperate, virulent, vociferous, volatile, waning,

waxing,

writ

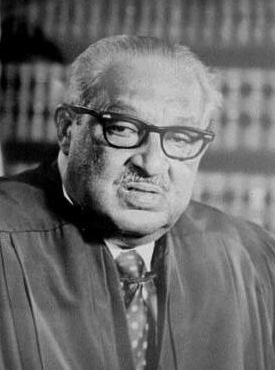

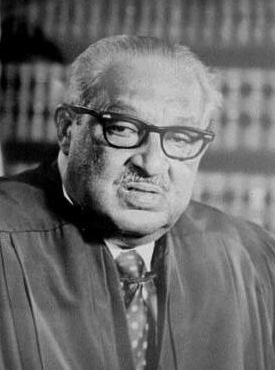

Thurgood Marshall,

U.S.

Supreme Court Justice

PDImages.Com

Thurgood Marshall, 1908-1993, civil rights

lawyer and chief council for the NAACP, brought down segregation in

America

with his 1954 victory in Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall

was

the first African American to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Return

to

Home Page

Last modified August 2006