Waterfront Redevelopment and the Puerto Madero

Project in Buenos Aires, Argentina

David J. Keeling

Department of Geography and Geology

Western Kentucky University

Bowling Green, KY 42101-3576

USA

Tel: 1-270-745-4555

Fax: 1-270-745-6410

Email: david.keeling@wku.edu

Abstract

Landscape

changes in the world’s major cities can be indicative of participation in and

engagement with the forces of globalization.

Although such changes are of great interest to geographers, who read and

analyze urban landscapes to interpret influences, meaning, social implications,

and identity, they are also very significant for others. Perceptions and impressions of a city formed

or created by business people, city boosters, tourists, residents, and

governments often are derived from the built landscape; transport

infrastructure, innovative buildings, open spaces, cultural facilities, and

physical attributes all contribute to how we “see” a city. Competition among cities to attract international

investment is fierce, and governments are learning that innovation and

creativity in infrastructural development are critical to gaining world-city

status and thus a share of the global economic potential.

Buenos Aires, Argentina, is an excellent exemplar of

urban landscape change in Latin America driven by conditions of

globalization. This paper examines the

Puerto Madero redevelopment project as indicative of the city's landscape

restructuring policies. Through a

detailed landscape and policy analysis, the strategies and implications of the

project are discussed and the role of globalization in driving the project is

critiqued. The paper concludes with an

analysis of the project's weaknesses and the broader implications for landscape

restructuring in this and other cities around the world.

Resumen

Los cambios del paisaje en las ciudades principales del mundo pueden ser indicativos de la participación en y del contrato con las fuerzas de la globalización. Aunque tales cambios están de gran interés a los geógrafos, que leen y analizan paisajes urbanos para interpretar las influencias, los sentidos, las implicaciones sociales, y la identidad, son también muy significativas para otras. Las opiniones y las impresiones de una ciudad formada o creada por la gente del negocio, los promotores de la ciudad, los turistas, los residentes, y los gobiernos se derivan a menudo del paisaje construido; la infraestructura de transporte, los edificios innovadores, los espacios abiertos, los recursos culturales, y los atributos todos contribuyen a cómo "vemos" una ciudad. La competición entre ciudades de atraer la inversión internacional es feroz, y los gobiernos están aprendiendo que la innovación y la creatividad en el desarrollo infraestructural son críticas a ganar estatus de la ciudad mundial y así una parte de la empanada financiera global.

Buenos Aires, la

Argentina, es un ejemplo excelente del cambio urbano del paisaje en América

Latina conducida por las condiciones de la globalización. Esta ponencia examina el proyecto de Puerto

Madero como indicar de las políticas de la reestructuración del paisaje de la

ciudad. Con un análisis detallado del paisaje y de política, las estrategias y

las implicaciones del proyecto se discuten y el papel de la globalización en

conducir el proyecto es criticado. La

ponencia concluye con un análisis de las debilidades del proyecto y de las

implicaciones más amplias para el paisaje que reestructura en esto y otras

ciudades alrededor del mundo.

Waterfront

Redevelopment and the Puerto Madero

Project in

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Introduction

Waterfront

redevelopment has emerged in recent decades as a central element in the

revitalization of urban areas.

Settlements with any kind of water frontage, whether it is on a river,

canal, lake, estuary, or ocean, are exploring ways to take advantage of the

environmental and aesthetic appeal of waterfront activities within the broader

context of urban renewal. The impetus for waterfront redevelopment is embedded

in the political, economic, social, and environmental forces that are

encouraging city governments to rethink the functionality and purpose of the

urban landscape. In addition, significant landscape changes are occurring as

cities participate in, and engage with, the processes of economic

globalization.

Although

such changes are of great interest to geographers, who read and analyze urban

landscapes to interpret influences, meaning, social implications, and identity,

they are also very significant for others.

Perceptions and impressions of a city formed or created by

businesspeople, city boosters, tourists, residents, and govern-ments often are

derived from the built landscape. Transport infrastructure, innovative

buildings, open spaces, cultural facilities, and physical attributes all

contribute to how we “see” and "experience" an urban

environment. Competition among cities

to attract international investment is fierce, and governments are learning

that innovation and creativity in infrastructural development are critical to

gaining world-city status and thus a share of the global economic potential.

Buenos Aires, Argentina, is an excellent exemplar of

urban landscape change in Latin America driven by conditions of globalization.

With the emergence of globalization both as an ideology and as a process in

Argentina beginning in the late 1980s, attention began to turn towards more

integrative urban planning and to development strategies designed to attract

international capital and capitalists.

The problem of addressing the city's run-down port area, known as Puerto

Madero, entered the local urban revitalization debate and emerged as a viable

rehabilitation project. This essay examines the Puerto Madero redevelopment

project as indicative of the city's landscape restructuring policies. Through

an analysis of the landscape and of the policies directed toward urban renewal,

the strategies and implications of the project are discussed and the role of

globalization in driving the project is critiqued. The essay concludes with an analysis of the project's strengths

and weaknesses and of the broader implications for landscape restructuring in

this and other cities around the world.

Globalization and Urban Landscape

Change

From a

theoretical perspective, globalization can be interpreted as the intersection

of the spaces of production (fordist or modernist functions), consumption

(postmodernist functions), and manipulation (global command and control

functions). New urban infrastructure is

created at the intersection of these three spaces, and waterfront redevelopment

is just one manifestation of this process.

Infrastructure is the visible expression of global and national capital

"touching down" on the local landscape to help create the conditions

that restructure the spaces of production, consumption, and manipulation. It is hypothesized that the nature of a

city's integration with the global economy is highly correlated with the degree

of infrastructural investment and development. Measuring such things as the

strength of engagement with the global economy, relative command and control

power, the degree of spatial influence, or the significance of new

infrastructure, for example, can provide important empirical evidence about the

processes of globalization and world-city development (Taylor et al.

2001).

Cities

that aspire to "global" status or that desire to participate more

profitably in the globalization process view new infrastructure as

critical. Integrated transport

services, quality educational facilities, cultural iconography, visually

stunning buildings, public spaces, and rehabilitated waterfronts, et cetera,

all are elements of the urban cultural landscape that reflect the strength of a

city's global engagement. Moreover,

infrastructure makes a visual statement about a city -- it can be a powerful

tool in creating and promoting an image of "globalization." For example, Sydney's international exposure

through hosting the 2000 Olympic Games derived in part from new infrastructure

built for the event, as well as from the existing cultural landscapes (Opera

House and Harbor Bridge) that stand out as symbolic of Sydney's status as a

"world city." Other cities

such as Seoul, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Tokyo, London, San Francisco,

São Paulo, and Buenos Aires have constructed buildings and facilities that

provide powerful visual evidence of engagement with globalization; for example,

the Docklands Light Railway, Petronas Towers,

Oriental Pearl Tower, the Tsing Ma Bridge, et cetera (Cybriwsky 1998; Ford 1998; Foster 1999; Keeling 1999; Kim

and Choe 1997).

Changes in

infrastructure, global trade linkages, urban land-use practices, and planning

policies all influence urban design, functionality, and aesthetic appeal. From an analytical perspective, two broad

frameworks for understanding urban landscape changes have developed since the

1980s (Fainstein 1996, Keeling 1999). At the global level, urban environments

are situated along a continuum of regional, national, and international systems

and researchers have analyzed such themes as uneven development, social

polarization, and competitive economic advantage within these systems. Soja’s

(1997) discourse on the contemporary city, or postmetropolis, for instance,

proposed the concept of “cosmopolis” to encompass the globalization of urban

capital, labor, and culture and the formation of a restructured hierarchy of

global cities. The urban impacts of

globalization are varied, complex, and have stimulated a "shift in the

attitudes of urban governments from a managerial approach to

entrepreneurialism" (Habitat 2001:26). The role played by global cities as

key economic command and control centers within the contemporary world-system

has encouraged much exciting research under the umbrella of world-city theory

(Friedmann 1986; Hall 1966; Knox and Taylor 1995). For example, examinations of Latin American cities such as Buenos

Aires (Keeling 1996, Torres 2001), Mexico City (Pick and Butler 1997; Ward

1998), and Havana (Segre et al. 1997) have drawn explicitly and implicitly on

the world city concept to explicate the relationship between local urban change

and global macroeconomic forces.

Research

on urban restructuring at the local scale explores the processes shaping the

essential character of a city from “the inside out” (Fainstein1996:170). Local actors, institutions, community

structures, labor divisions, levels of accessibility, cultural iconography, and

economic activities all drive urban restructuring in specific and mutually

reinforcing ways. The aim of this “view from below” theoretically is to mesh

the macro-level structuring of the city with, in Soja's (1997:21) words, the

“micro-worlds of everyday life” in order to understand more clearly spatial

changes in the urban fabric. Ford's (1998) analysis of world cities, for example,

highlights the dynamism and modernity of so-called "midtowns" and

"megastructures" and the role they play in the global identity of a

city. At the other end of the urban spectrum, Jakle and Wilson (1992) have

explored the problem of derelict landscapes in cities and the social and

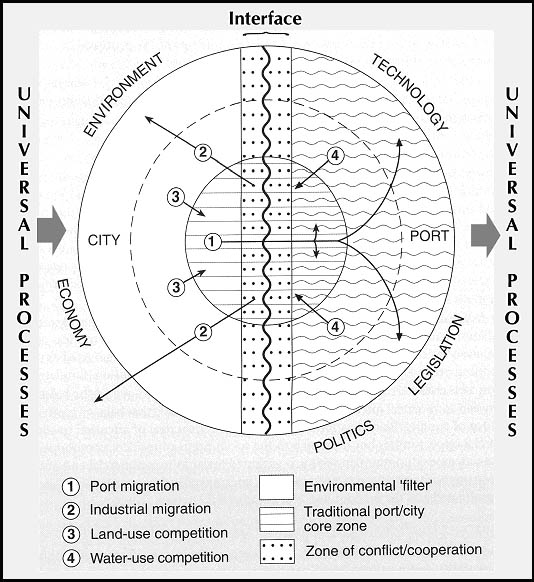

economic problems they generate. Hoyle (2000:413) has examined specifically the

changing nature of ports and waterfronts, focusing specific attention on the

intertwining of "universal processes [...] [with] individual locations and

environments" (Figure 1). The characteristics of this interface include

external or universal processes that both shape and are shaped by the

environmental, political, technological, economic, and legislative forces that

mediate port-city interaction.

In cities

as diverse as Liverpool and Marseilles, London and Sydney, or Baltimore and

Buenos Aires, waterfronts are emerging as new centers of social and economic

activity (Breen and Rigby 1996). Once

run-down and derelict urban land-scapes are being reborn as attractive areas

hosting retail and sporting facilities, as well as offices, hotels, educational

centers, and other specialty services.

Throughout the 20th century, and particularly in the post-World War Two

period (1950s to 1970s), the restructuring of the shipping industry

(containerization) accelerated the demise or deterioration of once-thriving

waterfronts. Port cities especially

faced the reality of abandoned warehouses, unproductive real estate often in

prime locations, decaying industrial landscapes, and unattractive and badly

polluted physical environments. Since the 1980s, however, changes in maritime

technologies and a renewed focus on urban renewal strategies stimulated, in

part, by globalization ideologies and processes have encouraged waterfront

revitalization projects. These projects have generated a significant body of

literature in the disciplines of urban planning, politics, environmental

management, cultural ecology, and geography (Hall 1993, Hoyle 2000).

As Hoyle

(2000:415) posited, the potential of waterfront redevelopment depends on three

things: "First, integration of past and present; second, integration of

contrasting aims and objectives; and third, integration of communities and

localities involved." This

approach to understanding the characteristics and implications of waterfront

revitalization can be applied to the Puerto Madero project in Buenos Aires,

Argentina. Between the 1920s and 1980s

a wide swath of the city's river frontage deteriorated progressively, to the

point where several hectares between the central city and the Río de la Plata

formerly occupied by the Madero port operations had become an eyesore,

frequented by urban squatters and transients and in serious decay. As the government of Argentina began to

embrace the ideologies of globalization at the end of the 1980s, it focused

renewed attention on both the role and the image of Buenos Aires in the global

system (Keeling 1996). Puerto Madero

particularly stood out as a symbol of failed urban renewal policies and as a

symptom of much that was wrong with the city's development ambitions. In

November 1989, presidential decree 1279/89 created the "Former Puerto

Madero Corporation" and charged it with developing a Master Plan for Urban

Development to revitalize the 170-hectare site. As Carlos Corach (1999:13), former Minister of the Interior,

observed, the Puerto Madero project is "much more than real-estate

development; it is the new plan that defines the future city. It is the road to follow to achieve a

destiny of progress and it is the new configuration of urban space that

emphasizes the public good."

Historical Puerto Madero

Internal

political struggles between Buenos Aires and the rest of Argentina following

independence in 1816 stymied the construction of a major port in the city. Not until the political compromise of 1880,

when the city of Buenos Aires became the +federal capital of Argentina, did

work commence on a modern port facility located in front of the city along the

Rio de la Plata shoreline (Scobie 1971).

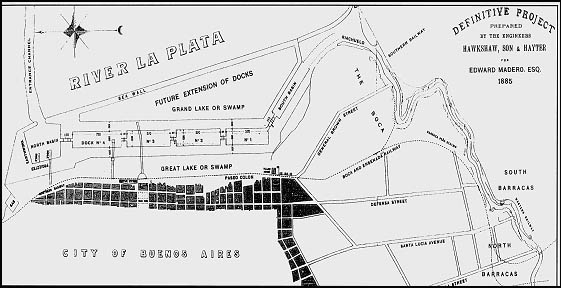

In 1881, engineers Eduardo Madero and John Hawkshaw proposed the

construction of two major channels, one to the south and the other to the north

of the main river channel, with two docks at the entrance of each channel. A series of parallel interconnected quays

would be located directly south of the Plaza de Mayo (the city center) and

would allow for significant expansion to the north of the central city (Figure

2).

Construction

began in 1887, with the port opening formally on January 28, 1889, and the four

parallel quays were inaugurated between 1890 and 1897. The development of

Puerto Madero ended three decades of political conflict, competing interests,

and unfulfilled potential for the city, allowing for significant expansion in shipping

operations. However, technical and operational problems with the port became

evident almost immediately, highlighting the lack of long-term planning and a

complete misunderstanding of the spatial dynamics of port operations. The facilities were totally inadequate for

loading and unloading, access and egress proved complicated, the channels could

not accommodate the rapid growth in vessel size, and the warehouses were

unsuitable for the types of goods being shipped. In 1919, construction on a new port began to the north of Puerto

Madero, and by 1925 the Madero facilities had fallen idle (D'Angelo 1963).

Various

rehabilitation projects were proposed over the next sixty years, starting with

the Organic Plan for Municipal Urbanization formulated between 1923 and 1935

and culminating in 1985 with a study of the area by the School of Architecture

at the University of Buenos Aires in partnership with the Secretary of State

and Transport. The eminent French urban

planner Le Corbusier (1947) recommended after a 1929 visit to Buenos Aires that

only strong and enforceable land-use and development laws could rescue Puerto

Madero from decay. His plan called for

the restoration of the riverfront as a symbol of the city's future and for the

construction of an artificial island -- the Cité des Affairs -- with five

skyscrapers. Unfortunately, political

crises, administrative jealousies, and the lack of a metropolitan development

strategy stymied any attempt at rehabilitating the port area. As a consequence of this inaction, the

administrative and commercial functions of the city spread northwards away from

the Plaza de Mayo-Puerto Madero axis and the historic central-city

neighborhoods of San Telmo, Monserrat, Barracas, and La Boca also fell into

decline. Buenos Aires had become a city

with its back to the river.

Contemporary Puerto Madero

Changing

national and international political and economic circumstances in the late

1980s encouraged a re-evaluation of the role of both Buenos Aires and Argentina

in the global economy. With the

election in 1989 of President Carlos Menem, a dramatic shift occurred in

Argentina's planning and development ideologies. Menem abandoned the traditional ideologies of the Peronist

political party (dirigismo or significant state intervention in the

economy and society) and turned the country toward neoliberalism and

globalization. Over the next few years,

so-called "structural adjustment" programs opened up the national

economy to global competition, privatized nearly all public services,

liberalized the financial and capital markets, and pegged the national currency

to the U.S. dollar on a one-for-one basis. Menem declared that Argentina now

belonged to a "single world ... a new juridical, political, social, and

economic order" (Gills and Rocamora 1992:515). Moreover, he argued that Buenos Aires, the national capital and

center of Argentine life, should play a central role in the country's

globalization strategies as a world city, an international gateway, and a key

economic center in South America.

As this

new ideology began to pervade the political and business arenas, both the mayor

of Buenos Aires and the president of the city's Urban Planning Council saw an

opportunity to revive the Puerto Madero redevelopment project. They realized,

however, that significant private investment, both local and international,

would be needed if the project were to have any chance of success. After intense negotiations between city and

federal government officials, the Corporación Antiguo Puerto Madero was

created in November 1989 and a redevelopment master plan was formulated in

cooperation with the Municipality of Barcelona, Spain. Barcelona had recently

completed a significant restoration of its own port environment and experts

from that project provided the Buenos Aires management team with ideas and

strategies for the Puerto Madero rehabilitation. The resulting master plan called for the construction of three

million square meters of covered space on 170 hectares of land, with a total

investment of 1.5 billion dollars.

With the

creation of a public-private partnership system designed to represent the many

competing political and economic interests, the next step involved untangling

the multiple jurisdictions that controlled property in Puerto Madero and

creating a mechanism to finance the redevelopment. Several provincial, federal, and municipal agencies, as well as

private corporations doing business in the area, used the docks, old

warehouses, and mills, as did hundreds of illegal squatters. To solve the

jurisdictional and financial problems, the federal government transferred

ownership of the land and the existing infrastructure to the newly established

corporation and required that the property be used to raise capital solely for

the redevelopment of Puerto Madero. Resolution of these problems marked the

first time in the urban planning history of Buenos Aires that the federal

government and the municipality had reached an agreement on a joint urban

development policy, especially one that would have such far-reaching

implications for the city.

When the

Barcelona experts delivered their strategic plan for the redevelopment of

Puerto Madero to the mayor of Buenos Aires in July 1990, protests erupted over

the lack of local participation in the project. Pressure from the Central Society of Architects, the Center of

Professional Architects and Planners, and other groups in Buenos Aires forced

the Corporation to establish the National Contest of Ideas for Puerto Madero. Design submissions were required to

demonstrate how Puerto Madero could be rescued from its deteriorated state and

reincorporated into the central city.

Moreover, residential areas had to be integrated with existing tertiary

uses, open green spaces had to be doubled, and recreational and cultural

activities had to be accommodated. The

final condition of the contest required that the historical heritage of the

site be included in the project design. Ninety-six submissions were received and

in February 1992 a panel of judges selected three winning teams, with three

representatives from each winning team responsible for developing the final

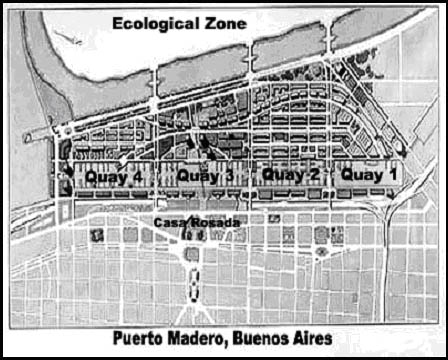

plan. In October 1992, the Corporation

unveiled the preliminary urban plan for the redevelopment of Puerto Madero,

which included a proposal to establish a cluster of residential towers and

office buildings at the edge of the project to mark the city's new limits on

the Río de la Plata (Figure 3).

Earlier in

1991, the Buenos Aires City Council had passed legislation designating the area

that included the docks, wharves, and warehouses fronting avenues Madero and

Huergo as the "Former Puerto Madero Area of Heritage

Protection." Conservation of the

sixteen red-brick warehouses that stretched 2.5 km along the western side of

the docks thus became a priority for the Corporation. The warehouses were

designed in England, shipped to Argentina in sections, and assembled in place

between 1900 and 1905. With covered

verandahs, platforms facing the water, and cranes attached to the walls, the

buildings were outstanding examples of 19th-century English industrial

architecture and the government considered them of significant cultural and

historic value. With a stipulation that

the external façades remain, the first five warehouses located on the north side

of the docks near the Retiro transportation complex were sold by public tender

in late 1991. The sale raised

approximately 20 million dollars for the Corporation, with a further 45 million

dollars pledged as investment in the rehabilitation of the warehouses. Construction began in September 1992 with

the gutting of the warehouse interiors (Figure 4) and restaurants, bars, and

office suites soon began to emerge from the rubble (Figure 5). Sale of the remaining warehouses occurred in

late 1992, with ten million dollars raised for the Corporation and the promise

of a further 40 million dollars in renovation investment. Especially important for the mixed-use

strategy of the development was the awarding of four warehouses on Quay 2 to

the Argentine Catholic University for its new city campus.

As the

warehouses metamorphosed into new commercial outlets, apartments, and office

space, work began on the two towers that serve as "gateways" to the

northern (Telecom Building) and southern (Malecón Building) ends of the

project. In addition, work began on

repairing the sidewalks, esplanades, bridges, and access roads that connected

the various areas of Puerto Madero. The

influx of new businesses and people to Puerto Madero had immediate positive

impacts on the Catalinas Norte office complex located at the northern end of

the project in front of the Retiro transportation center (Figure 6). New

buildings sprang up as the area quickly emerged as the premier office center in

Buenos Aires. At the southern end of

Puerto Madero, completion of the La Plata freeway connection, construction of

the "intelligent" Malecón office tower, the development of the

university campus, and the opening of a state-of-the-art cinema complex on quay

one signaled the potential redevelopment of the adjacent San Telmo, Barracas,

and La Boca barrios. These

neighborhoods had deteriorated significantly since the 1940s and 1950s, when

the development thrust of the central city had turned to the north and west,

away from the river and away from the historic southern quarter.

By 1997,

most of the redevelopment work on the western side of Puerto Madero had been

completed and attention now turned to the eastern side of the quays. In keeping

with the mixed-use strategy adopted by the Corporation, construction began on

hotels, office buildings, apartment towers, parks, a parish church, new

museums, another cinema complex, and a conference center. Anchoring the central part of the project

is the five-star Hilton Hotel (Figure 7), with a 4000-square meter convention

center, surrounded by office buildings and apartment complexes. To the south,

three industrial buildings of historical significance to the city will be

preserved and renovated: the Di Tella Foundation is converting the flour mill

at quay 3 into a series of university research institutes; the El Porteño mill

on quay 2 is to become a luxury hotel remodeled by French designer Philippe

Starck (Figure 8); and the large grain elevator on quay 3 will be merged into

the Madero Este project (Figure 9).

Finally, to link this central area of Puerto Madero, especially the

Hilton Hotel and its surrounding offices and apart-ments, to the city center, a

swinging pedestrian footbridge has been constructed across quay 3 (Figure 10).

Other projects designed to increase the aesthetic and

touristic appeal of Puerto Madero included the relocation of two museum ships

to quays one and two respectively and the development of large public

spaces. All of the streets and parks within

the redevelopment zone have been renamed after women who have made cultural and

humanitarian contributions to Argentina. Sculptures have been erected at key

inter-sections, trees and benches are located along the main esplanades and

also at key intersections, and information boards in Spanish, English, and

Portuguese are placed strategically around the entire area. Upwards of 100 million dollars also have

been invested in basic service infrastructure such as power and water lines,

sewer systems, data and voice lines, rehabilitated bridges, and street

signage. In recognition of the

significant metamorphosis of this once-derelict area, the city government

incorporated Puerto Madero on September 9, 1998, as the official 47th

barrio of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires.

As of November 2001, the original

170-hectare site is divided between three specific uses: the quays and other

waterways cover 39.5 hectares, public spaces account for 69.1 hectares, and the

remaining 61.4 hectares have been urbanized or designated for residential or

commercial use. Construction remained

active on fourteen different projects within the zone, with total private

investment in completed projects and in works-in-progress exceeding two billion

dollars. However, the political and

economic collapse experienced by Argentina in December 2001 has cast a dark

cloud over the entire Puerto Madero project, particularly in light of the

abandonment of the Convertibility Law that has spurred a rapid devaluation of

the Argentine peso relative to the US dollar.

Project Evaluation

and the Future of Puerto Madero

In terms of the original goals of

the governments, planners, business interests, and institutions involved in the

Puerto Madero project, the overall redevelopment of the area has been a

resounding success. Jurisdictional

conflicts were overcome, the lack of public funding did not stymie private

investment, the entire zone has been physically and aesthetically rejuvenated,

thousands of people daily flow through the area, and the city indeed has turned

its face back towards the Río de la Plata.

Moreover, the redevelopment of Puerto Madero has encouraged new public

and private investment in riverfront areas to the north and south of the

project, although not at the level enjoyed by Puerto Madero. Although there have been complaints about

corruption throughout the twelve years of the project, as well as charges of

mismanagement of Corporation funds, public attitudes about the area and its

facilities on balance have been generally positive.

Referring

back to Hoyle's (2000) three keys to potential waterfront redevelopment, the

Puerto Madero project certainly achieved the first objective of integrating the

past and present. The turn-of-the-century warehouses, in particular, serve as

functional, aesthetic, and historical anchors for the project. Integration of contrasting aims and

objectives into the project design, the second objective, has been less

successful, although a balance has been achieved in Puerto Madero between

public and private needs and uses.

Achievement of the final objective, integration of communities and

localities involved, is still subject to substantial debate, as some significant development issues remain unresolved.

Puerto Madero still is poorly served by public transport and

is not well integrated with the urban transit network. Access and egress to the zone by pedestrians

remain difficult and dangerous, especially across the two major boulevards that

separate Puerto Madero from the city center. Buenos Aires also lacks any

sophistication in its tourism marketing and promotion vis-a-vis the new area,

and there is little evidence that Puerto Madero’s attractions have been

meaningfully articulated with the city’s major tourist destinations. Plans for the connection of the La Plata

freeway in the south to the northern freeway remain in limbo. The Corporation

is opposed to either a ground-level or elevated freeway that would pass in

front of the rehabilitated warehouses, arguing that such a plan would create

both physical and aesthetic problems and inhibit further growth in Puerto

Madero. A proposal to bury the freeway

link in a tunnel underneath Madero and Huergo avenues is on the drawing board,

but the costs of such a project, especially in light of the nation’s bankruptcy

in early 2002, remain prohibitive. A

third proposal to extend the freeway link across the ecological zone that lies

between the new development and the Río de la Plata has met with vociferous

resistance by planners and environmentalists.

Although a railroad line runs parallel to Puerto Madero, providing a

rush-hour passenger service from the western suburbs, the infrastructure is in

very poor repair and needs significant investment in new track, signaling, and

rolling stock.

Criticism has been leveled against

the project by community action groups and others who have argued that the

funds generated by the sale of public land in Puerto Madero could have been

better invested in social welfare projects elsewhere in the city. Critics complain that Puerto Madero has

achieved its goal of creating an urban landscape worthy of globalization and

world-city status all too well, effectively excluding the masses of Buenos

Aires from engaging with the project in any meaningful way. The rehabilitation of Puerto Madero has

articulated Buenos Aires and Argentina more forcefully with the global economy

and its circuits of international capital, yet it has disarticulated the area

from the basic socio-economic rhythms of the city. In light of Argentina’s economic crisis at the beginning of 2002,

the Puerto Madero project may reveal a significant vulnerability to its

dependence on global capital and the trans-national elite. Will there exist sufficient financial

stimuli to see the remaining development through to completion, or will much of

Puerto Madero stagnate once again and become a huge, unfinished construction

zone? Moreover, is there sufficient

demand in the local, national, regional, and global economies to sustain the

businesses already committed to the area?

Bankruptcies and failures rippling through the Argentine economy may

well wreak havoc on Puerto Madero in the months and years ahead.

Returning to Hoyle’s (2000) characteristics of the

port-city-global interface (see Figure 1), it is evident from examining the

Puerto Madero experience that universal processes played a critical role in the

redevelopment of this landscape. It is

unlikely that port redevelopment projects of any significant size around the

world could succeed today without serious engagement with global capital and

international management. However, in

less-robust economies this global engagement could well signify an increased

level of project vulnerability and a lower certainty of long-term success. Building new and rehabilitated

infrastructure may be a prerequisite for increased global engagement and world

city activities, but it may also prove to be a serious economic burden that

could accelerate the collapse of a weakening domestic economy. Should this happen in Buenos Aires, the city

might face renewed conflict over land-use planning and development strategies

and could be forced to rethink the level of its engagement with globalization

and world-city strategies.

Acknowledgments

A version of this paper was

presented at the 2001 CLAG conference in Benicassim, Spain, in May 2001. The author acknowledges the assistance in

Buenos Aires of Dr. Juan Alberto Roccatagliata, the National Archives, the

Corporación Antiguo Puerto Madero, and the City of Buenos Aires municipal

government.

References

Archivo

General de la Nación (1885) Documentos y planos del Puerto Madero. Buenos

Aires: Archivo General de la Nación.

Beaverstock,

J.V., R.G. Smith, and P.J. Taylor (2000) World city network: a new

meta-geography? Annals, Association of American Geographers,

90(1):123-34

Breen, A.

and D. Rigby (1996) The New Waterfront: A Worldwide Urban Success Story. London: Thames and Hudson.

Corach,

Carlos V. (1999) Introduction, pp. 13-14 in 1989-1999: Corporación Antiguo

Puerto Madero, S.A. Un modelo de gestión urbana. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Larivière.

Corporación

Antiguo (1999) 1989-1999: Corporación Antiguo Puerto Madero, S.A. Un modelo

de gestión urbana. Buenos Aires:

Ediciones Larivière.

Cybriwsky,

Roman (1998) Tokyo: The Shogun's City at the Twenty-First Century. New

York: Wiley.

D'Angelo,

J.V. (1963) La conurbación de Buenos Aires, pp. 90-219 in F. de Aparicio and

H.A. Difrieri (eds.), La Argentina: Suma de Geografía, Vol. 9. Buenos

Aires: Ediciones Peuser.

Fainstein,

S.S. (1996) The changing world economy and urban restructuring, pp. 170-186 in

S. Fainstein and S. Campbell (eds.) Readings in Urban Theory. Cambridge,

MA: Blackwell.

Ford,

Larry R. (1998) Midtowns, megastructures, and world cities. Geographical

Review 88(4):528-547.

Foster, J.

(1999) Docklands: Cultures in Conflict, Worlds in Collision.

Philadelphia: UCL Press.

Freidmann,

John (1986) The world city hypothesis. Development and Change

17(1):69-84.

Gills, B.

and Rocamore, J. (1992) Low intensity

democracy. Third World Quarterly 13(3):501-523.

Habitat

(2001) Cities in a Globalizing World. London: Earthscan (U.N. Center for

Human Settlements).

Hall,

Peter (1993) Waterfronts: A new urban frontier, pp. 12-19 in R. Bruttomesso

(ed.), Waterfronts: A New Frontier for Cities on Water. Venice:

International Centre Cities on Water.

Hall,

Peter (1966) The World Cities. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Hoyle,

Brian (2000) Global and local change on the port-city waterfront. Geographical

Review 90(3):395-417.

Jakle,

J.A. and D. Wilson (1992) Derelict Landscapes: The Wasting of America's

Built Environments. Savage, MD:

Rowman & Littlefield.

Keeling,

David J. (1999) Neoliberal Reform and Landscape Change in Buenos Aires,

Argentina. Yearbook 1999, Conference of

Latin Americanist Geographers

25:15-32.

Keeling,

David J. (1996) Buenos Aires: Global

Dreams, Local Crises. New York: John Wiley.

Kim, J.

and S-C Choe (1997) Seoul: The Making of a Metropolis. New York: Wiley.

Knox, P.L.

and Taylor, P.J. (eds.) (1995) World Cities in a World-System.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Le

Corbusier (1947) Proposición de un Plan Director para Buenos Aires.

Buenos Aires: Muncipalidad de Buenos Aires.

Pick, J.B.

and Butler, E.W. (1997) Mexico Megacity. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Scobie,

James (1971) Argentina: A City and a Nation. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Segre, R.,

Coyula, M., and Scarpaci J.L. (1997) Havana: Two Faces of the Antillean

Metropolis. New York: Wiley.

Soja,

Edward W. (1997) Six discourses on the

postmetropolis, pp. 20-30 in S. Westwood and J. Williams (eds.) Imagining

Cities: Scripts, Signs, Memory. New York: Routledge.

Taylor,

P.J., M. Hoyler, D.R.F. Walker, and M.J. Szegner, M.J. (2001) A new mapping of

the world for the new millennium. The Geographical Journal

167(3):213-222.

Torres,

Horacio A. (2001) Cambios socioterritoriales en Buenos Aires durante la década

de 1990. Revista Eure 27(80): 33-56.

Ward. Peter M. (1998) Mexico

City (2nd edn.). New York: John Wiley.

Figure

1. Characteristics of the

Port-City-Global Interface.

Source:

Modified from Hoyle (2000:404)

Figure

2. The

Madero and Hawkshaw Plan, 1885.

Source:

Archivo General (1885).

Figure

3. The Puerto Madero Zone, Buenos

Aires.

Source:

Modified from Corporación Antiguo (1999).

Figure

4. Reconstruction of the warehouses.

Source:

Photo by the Author, 1992.

Figure

5. Rehabilitated Warehouse in Puerto

Madero.

Source:

Photo by the Author, 1995

Figure

6. The Telecom Tower and Catalinas

Norte

at the

Northern End of Puerto Madero

Source:

Photo by the Author, 2001.

Figure

7. The Hilton Hotel in central Puerto

Madero.

Source:

Photo by the Author, 2001

Figure

8. The El Porteño Mill Scheduled for

Conversion to a Luxury Hotel

Source:

Photo by the Author, 2001.

Figure 9. Construction underway on Madero Este,

to include

office buildings and apartments

Source:

Photo by the Author, 2001.

Figure

10. The Puente de La Mujer

(Woman's Bridge),

designed

by Santiago Calatrava,

linking

central Puerto Madero to the City Center

Source:

Photo by the Author, 2001.